**Trigger Warning: This article discusses sexual assault**

The seeming ordinariness of the defendants in France’s mass rape trial has shocked the country – which, for the most part, appeared to dismiss 2017’s #MeToo movement – into a renewed reckoning.

At the hands of her husband, Gisèle Pelicot was drugged and raped by up to 80 strangers he recruited from the internet. Dominique and Gisèle had been together since 1973, when they were 19. They have three adult children and seven grandchildren. In her memoir, their daughter wrote that he was the “perfect doting dad”.

Between 2011 and 2020, he crushed up sleeping pills and anti-anxiety medication into his wife’s dinner and drinks, and once she was in bed, he’d text a waiting stranger that it was time to come in. Dominique filmed while these strangers sexually abused his wife.

Gisèle had no idea what had been happening to her until a serendipitous intervention in 2020. A supermarket security guard caught Dominique taking upskirt photos of women, and when the police seized his phone, they found the images of Gisèle.

“My world fell apart. For me everything was falling apart,” Gisèle told the court of the moment the police showed her the images. She didn’t recognise herself in the foetal position in her bedroom – or the men. “It was unbearable. I was inert, in my bed, and a man was raping me.”

Dominique and 50 other defendants went on trial in early September in Avignon in southern France. Gisèle, who’d changed her name in her divorce, waived her right to anonymity and is using her married name during the trial.

“I speak for all women who are drugged and don’t know about it,” she said. “I do it on behalf of all women who will perhaps never know.”

MeToo Stalled In France

Hollywood’s #MeToo movement, which went viral in 2017 following the sexual abuse claims against film producer Harvey Weinstein, touched nearly every industry in nearly every country. In Australia, we’re still seeing it play out in our hospitality industry.

But in France, it was largely dismissed. The country has long struggled with recognition and accountability of sexual misconduct and misogyny. In 2018, more than 100 French women signed a letter denouncing the #MeToo movement, viewing it less as a way to protect women and more a sign that a very American brand of feminism had washed up on its shores.

Essentially, the movement was stalled. There were small changes, but it was more of a subtle shift than an overhaul of an entire industry.

This year, though, the French #MeToo movement has emerged with renewed energy, and misogynists and abusers look less likely to escape unscathed this time. The New York Times reported in April that after experiencing abuse when she was younger, the actor and director Judith Godrèche has been campaigning to “expose the abuse of children and women that she believes is stitched into the fabric of French cinema”.

Along with a strong media presence, she also appeared before the French Parliament and demanded an inquiry into sexual violence in the industry and protective measures for children. In February, she was invited to give a speech at the Césars (the French Oscars), and she took the opportunity to ask how the industry could collectively accept “that this art that we love so much, this art that binds us” is used as a cover to abuse girls.

“French attitudes toward morality and sex have historically always been different to the US,” journalist Agnès Poirier told the BBC. “But it’s been brewing for years, and it feels that 2024 is different.”

And it’s young women leading the charge. “While there is still perhaps more scepticism in France than in the US about the legitimacy of sexual assault and sexual harassment, these attitudes are changing fast, especially as a younger generation of women and French feminists and their male allies … are willing to confront these issues head-on,” Laura Frader, a professor of history emerita at Northeastern University who studies gender attitudes in Europe, told Vox. “The Pelicot case is certain to contribute to this trend.”

We Are All Gisèle

Gisèle’s case is shining a spotlight on rape and sexual abuse in ordinary people’s everyday lives. She has become a symbol of the fight against sexual violence.

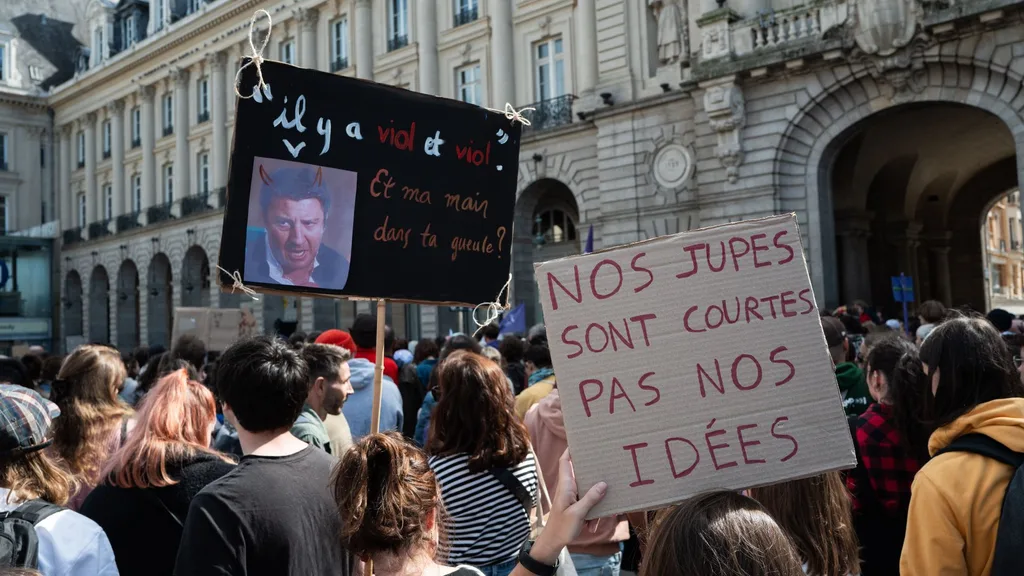

On the first day of the trial, on September 2, more than a dozen protestors dressed in black stood outside the courthouse as it started. Over the weekend of September 14, the protestors grew in number and in volume across the country.

In Paris, a large crowd chanted, “We are all Gisèle.” In Marseille, about two hours further south from Avignon, protestors hung a banner on the court building that read “Shame must change sides” – a quote from Gisèle via her lawyers about how women shouldn’t bear the guilt and burden of being assaulted. The ABC reported that in Rennes, on the opposite side of the country, a young woman held a sign on which she’d written “Protect your daughters”, crossed it out and replaced it with “Educate your son.” Among the protestors was the actor Charlotte Arnould, who has accused the French actor Gerard Depardieu of rape. (Another woman, a set designer, has also accused him of assaulting her, and a third woman, actor Hélène Darras, accused him of groping and propositioning her.)

“It’s very important to be here because we need to talk about the rape culture,” Anna Toumazoff, an activist and one of the organisers of the Paris protest, told AP News. “After seven years of MeToo, we know that there is not a special type of victim. We are also collectively realising that there is no special type of a rapist.”

Many of Gisèle’s attackers appeared to be ordinary men with ordinary jobs leading ordinary lives. They include her husband, her neighbour, a firefighter, a former police officer, a local councillor, nurses, a soldier, a journalist, truck drivers and a civil servant: more than 70 men aged 26 to 73 when they were arrested. Of the 50 who are on trial, 18 are in custody and 32 are attending the trial as free men. One is yet to be found and will be tried in absentia. There are reportedly up to 30 more men in the recordings who detectives were unable to trace.

On September 17, when Gisèle was leaving court, she was met with a huge crowd and rapturous applause, with one man even handing her a huge bunch of flowers. She’s become a hero in the fight against sexual violence in France.

The Question Of Consent

Hélène Devynck, an advocate for France’s #MeToo movement, wrote about Gisèle’s case in the French newspaper Le Monde. “[The men think] they have the right. They have the power to do it,” she wrote. “They were raised on the hatred of women, on the contempt that revels in the powerlessness of the other. … They did what most accused men do: they made themselves out as victims and added another layer of contempt to the woman they had already humiliated.”

While some of Gisèle’s abusers – including her ex-husband – have pleaded guilty to rape, others have said it wasn’t rape, that Dominique tricked them. One reportedly went so far as to claim “consent by delegation”: her husband said it was okay, so that’s enough. “He does what he wants with his wife,” Le Monde reported the man as saying. “As long as the husband was there, there was no rape”.

“It sends shivers down the spine regarding the state of affairs in French society,” said Gisèle’s lawyer Antoine Camus, who is also representing Gisèle and Dominique’s daughter (who Dominique is also accused of drugging and photographing) and other family members. “If that’s the conception of consent in sexual matters in 2024, then we have a lot, a lot, a lot of work to do.” Consent is a contested grey area in France. In French law, it’s defined as an “act of sexual penetration” committed “by violence, coercion, threat or surprise”. Women’s rights advocates and lawmakers want to amend that wording to say explicitly that sex without consent is rape, that consent can be withdrawn at any time, and that consent cannot exist if sexual assault is committed “by abusing a state impairing the judgment of another”. French President Emmanuel Macron has said he supports the move.

During the trial, defence attorney Paul-Roger Gontard said: “There’s rape and there’s rape,” seemingly trying to make it seem like the defendants were guilty of rape-lite – a sex game with a willing couple gone wrong, in which Gisèle was an accomplice. “No, there are no different types of rape,” Gisèle responded. “Rape is rape.” Gontard apologised, saying he was trying to differentiate between the legal definition of rape and the “media” definition. “I am sorry that these remarks hurt and shocked you.” (Apology-lite.)

Australia, Too

While the MeToo movement continues to reverberate throughout Australia, touching almost every industry, we’re still dealing with problematic attitudes towards women and consent.

According to research from the author Dr Anita Heiss, a shocking 48 per cent of Australians don’t understand what consent actually means.

Dr Siobhan O’Dean, a postdoctoral research fellow at The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use at the University of Sydney, has also seen concerning evidence of pervasive misogynist views.

“Although attitudes toward sexuality and consent have evolved in Australia, there is still some evidence that misogynistic beliefs persist, especially when it comes to sexual entitlement and male dominance in relationships,” she says. She cites the 2022 National Community Attitudes Towards Violence Against Women Survey (NCAS), which showed that “a significant number of Australians still hold outdated views on gender roles and consent. For example, a significant portion of respondents agreed that if a woman is married, her husband is justified in having sex with her, even if she makes clear she does not want to.”

Sue Heward-Belle is a professor at the University of Sydney and a recognised leader in domestic and family violence research. She says these attitudes are common in violent offenders. “[They often have] an exaggerated sense of entitlement coupled with a very underdeveloped sense of responsibility for others,” she says. “You can see it in the audacity to think that a husband gives consent for his wife, who – in Gisèle’s case – was not able to give consent in any way. It’s incredible to think an adult male would use that to justify his own behaviour.”

Help Is Available:

- If you require immediate assistance, please call 000.

- If you’d like to speak to someone about intimate partner violence, call the 1800 Respect hotline on 1800 737 732 or chat online.

- If you’re under 25, you can reach Kid’s Helpline at 1800 55 1800 or chat online.

This article originally appeared on Marie Claire Australia and is republished here with permission.