A giant rift is slowly tearing Africa, the second-largest continent, apart. This depression — known as the East African Rift — is a network of valleys that stretches about 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) long, from the Red Sea to Mozambique, according to the Geological Society of London.

So will Africa rip apart completely, and if so, when will it split? To answer this question, let's look at the region's tectonic plates, the outer parts of the planet's surface that can collide with each other, making mountains, or pull apart, creating vast basins.

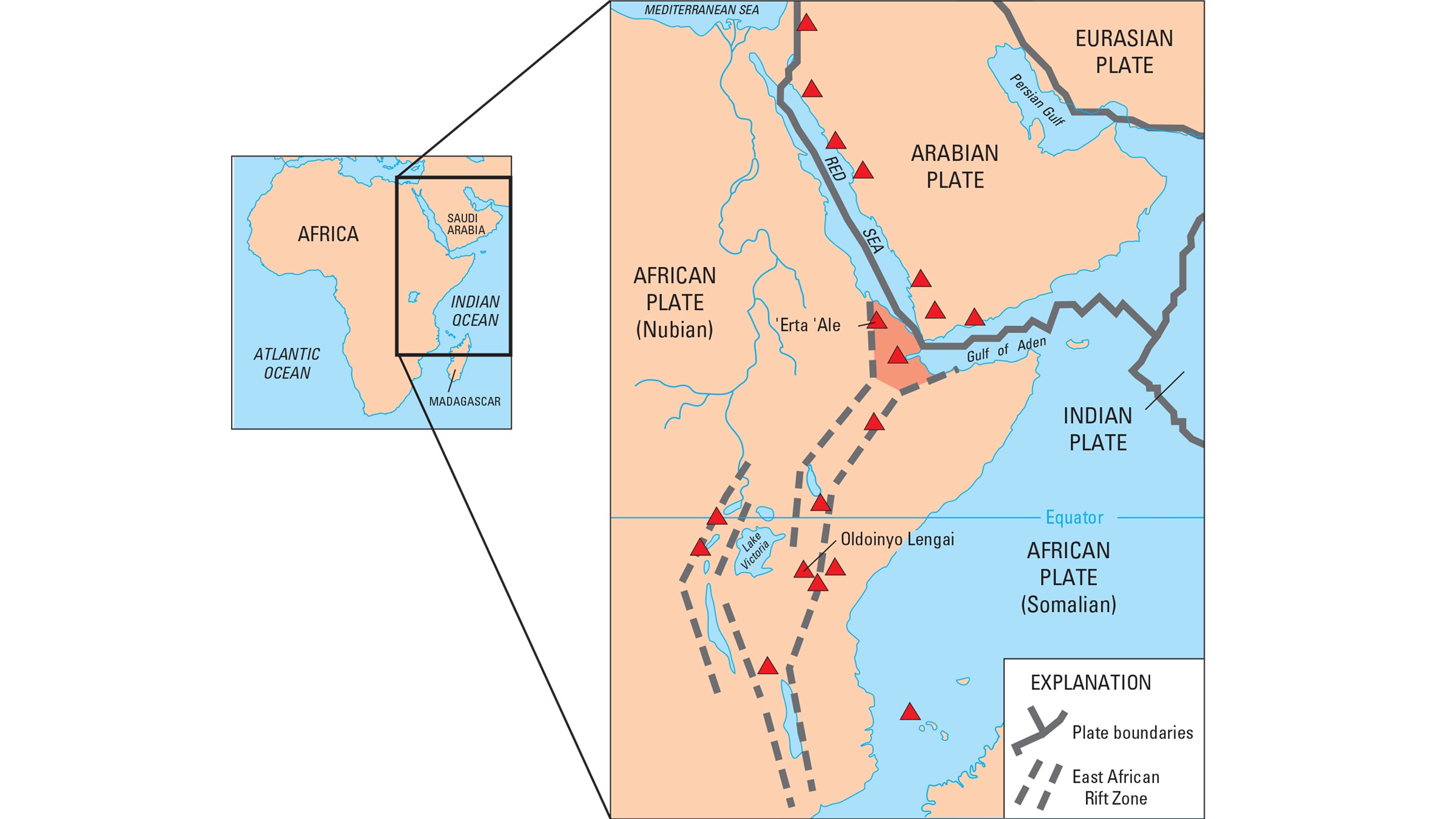

Along this colossal tear in eastern Africa, the Somalian tectonic plate is pulling eastward from the larger, older part of the continent, the Nubian tectonic plate, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. (The Somalian plate is also known as the Somali plate, and the Nubian plate is also sometimes called the African plate.)

The Somalian and Nubian plates are also separating from the Arabian plate in the north. These plates intersect in the Afar region of Ethiopia, creating a Y-shaped rift system, the Geological Society of London noted.

Related: Which is the largest continent? The smallest?

A slow break

The East African Rift started forming about 35 million years ago between Arabia and the Horn of Africa in the eastern part of the continent, Cynthia Ebinger, chair of geology at Tulane University in New Orleans and a science adviser to the U.S. State Department's Bureau of African Affairs, told Live Science. This rifting extended southward over time, reaching northern Kenya by 25 million years ago.

The rift consists of two broadly parallel sets of fractures in Earth's crust. The eastern rift passes through Ethiopia and Kenya, while the western rift runs in an arc from Uganda to Malawi, the Geological Society of London noted. The eastern branch is arid, while the western branch lies on the border of the Congolese rainforest, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

The existence of the eastern and western rifts and the discovery of offshore zones of earthquakes and volcanoes indicate that Africa is slowly opening along several lines, which together amount to more than 0.25 inch (6.35 millimeters) per year, Ebinger said.

"The rifting right now is very slow, about the rate that one's toenails grow," Ken Macdonald, a distinguished professor emeritus of Earth science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told Live Science.

The East African Rift most likely formed because of heat flowing up from the asthenosphere — the hotter, weaker, upper part of Earth's mantle — between Kenya and Ethiopia, according to the Geological Society of London. This heat caused the overlying crust to expand and rise, leading to stretching and fracturing of the brittle continental rock. This led to substantial volcanic activity, including the formation of Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa, NASA's Earth Observatory noted.

If Africa does rip apart, there are different ideas for how that might happen. One scenario has most of the Somalian plate separating from the rest of the African continent, with a sea forming between them. This new landmass would include Somalia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and the eastern parts of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique, Ebinger said. "Another scenario has only eastern Tanzania and Mozambique separating," Ebinger noted.

If the African continent does rupture, "the rift in Ethiopia and Kenya may split to create a Somali plate in the next 1 million to 5 million years," Ebinger said.

However, Africa may not split in two. The geological forces driving the rifting might prove too slow to separate the Somalian and Nubian plates, Ebinger said. One notable example of a failed rift elsewhere on the globe is the Midcontinent Rift, which curves for about 1,900 miles (3,000 km) across the Upper Midwest of North America, according to a 2022 review in the journal GSA Today.

"Failed rifts mark continental landmasses worldwide," Ebinger said.

The eastern branch of the East African Rift is a failed rift, according to the Geological Society of London. However, the western branch is still active.

"What we do not know is if this rifting will continue on its present pace to eventually open up an ocean basin, like the Red Sea, and then later to something much larger, like a small version of the Atlantic Ocean," Macdonald said. "Or might it speed up and get there more quickly? Or it might stall out?"