The private Odysseus lander is down on the lunar surface, in more ways than one.

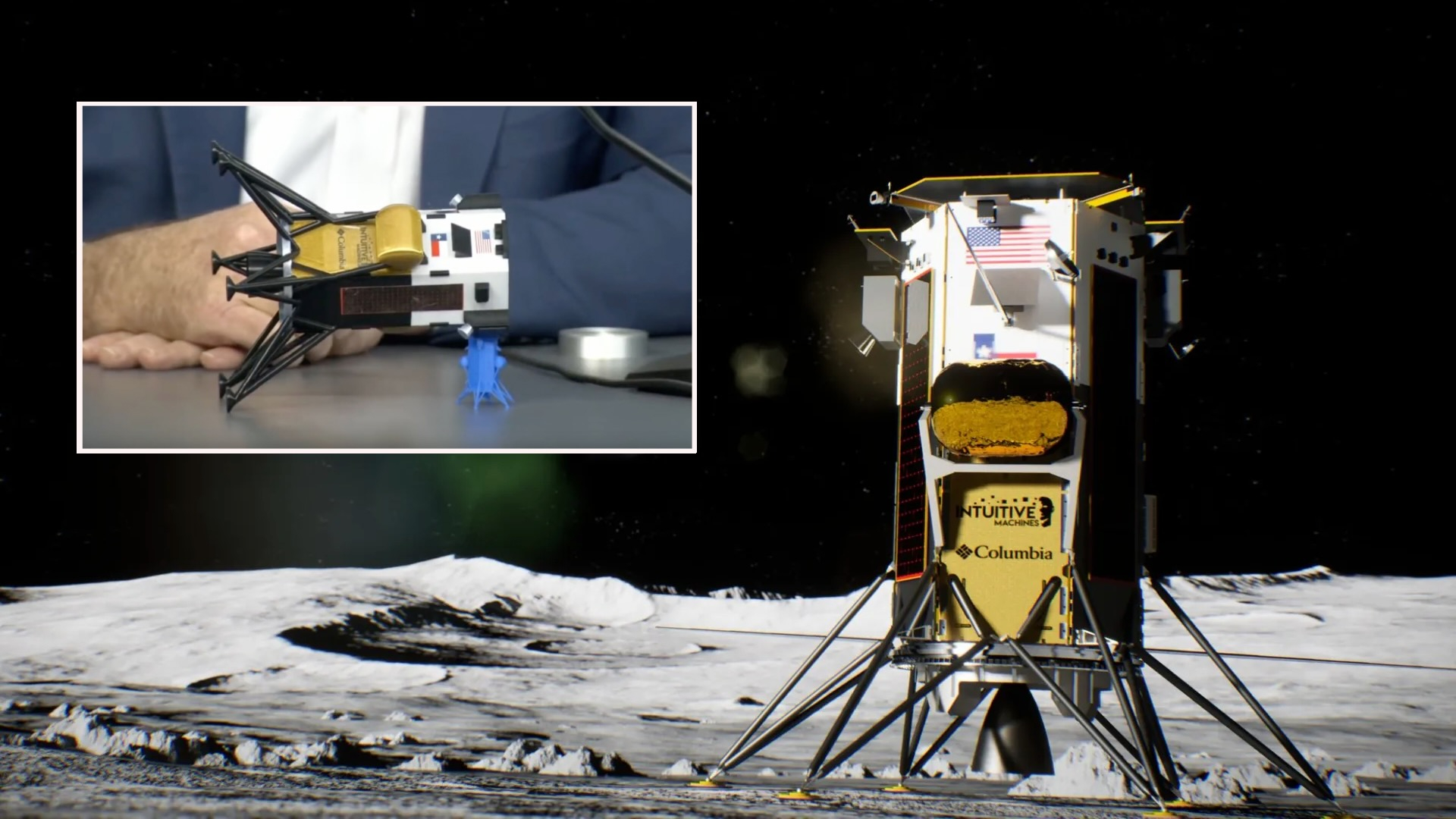

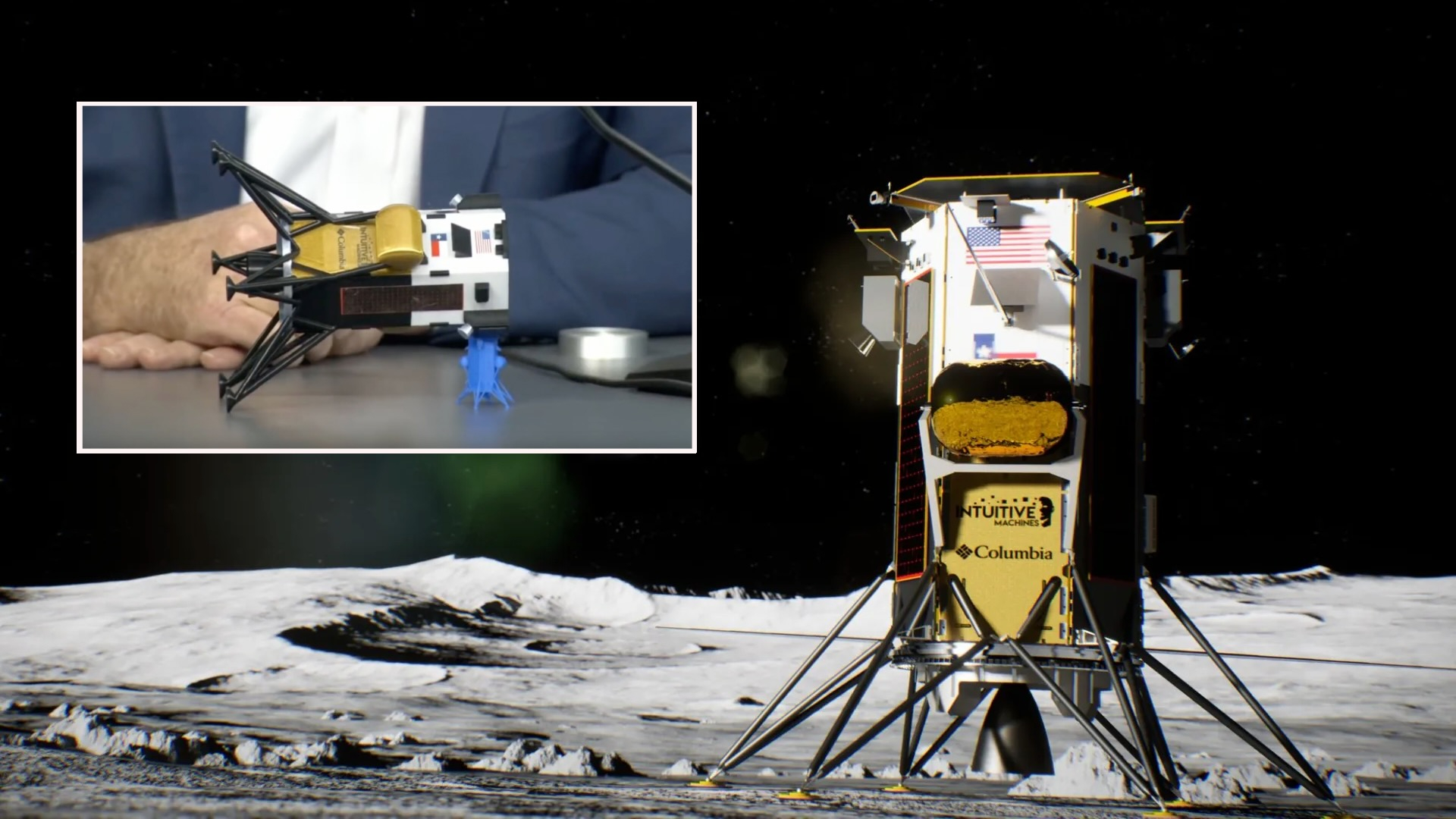

The 14-foot-tall (4.3 meters) Odysseus, which was built by Houston company Intuitive Machines, apparently settled on its side during its historic touchdown yesterday (Feb. 22), mission team members said. But don't panic — the pioneering spacecraft is still very much alive.

"So far, we have quite a bit of operational capability even though we're tipped over," Intuitive Machines CEO and co-founder Steve Altemus said during a press briefing today (Feb. 23).

"And so that's really exciting for us, and we're continuing the surface operations mission as a result of it," he added.

Odysseus launched on Feb. 15 atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, carrying six NASA science instruments and six private payloads toward the moon. The lander arrived in lunar orbit six days later and touched down yesterday evening, about 190 miles (300 kilometers) from the moon's south pole.

It was the first successful lunar landing by an American vehicle since the end of the Apollo era in 1972, and the first-ever by a private spacecraft.

And it took some quick thinking by the mission team to pull it off.

As the target landing time neared yesterday, Odysseus' handlers realized that its laser rangefinders weren't working properly. So they implemented a workaround to get the required altitude and velocity data, pressing into service an experimental NASA instrument aboard Odysseus called NDL ("Navigation Doppler Lidar for Precise Velocity and Range Sensing)."

The team delayed the planned touchdown by two hours to make the fix, which required them to beam a software patch to Odysseus from mission control in Houston.

"It was quite a spicy seven-day mission to get to the moon," Altemus said today.

The landing came with a little extra dash of flavor as well, the team announced today. While they're still analyzing data, it's pretty clear that Odysseus didn't land vertically as intended, Altemus and Tim Crain, Intuitive Machines co-founder and CTO, said during today's briefing.

During its final descent, Odysseus was supposed to be traveling about 2 mph (3.2 kph) in the vertical direction and 0 mph horizontally. But the data show it was actually moving at roughly 6 mph (10 kph) vertically and 2 mph (3.2 kph) horizontally, Altemus said.

He offered a theory about what happened: Perhaps, while coming down at those slightly off-nominal speeds, Odysseus caught one of its landing legs in a crevice or other piece of lunar terrain.

As a result, "we might have fractured that landing gear and tipped over gently," he said.

More data are needed before the team can make a full assessment. Some particularly revealing information could come from another payload aboard Odysseus: EagleCam, a system built by students at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University that was supposed to deploy from the lander during its descent and photograph the touchdown from the lunar surface.

The mission team decided to keep EagleCam aboard during landing, however, due to the navigational difficulties. It's still on the spacecraft, but the team plans to deploy it soon, hopefully getting some good ground-level shots of Odysseus as it now lies.

Like EagleCam, Odysseus' other instruments and important subsystems appear to be functional, Altemus said.

"We have the sun impinging on the solar arrays and charging our batteries," he said. "We are providing power to the spacecraft, and we're at 100% state of charge. That's fantastic."

The data suggest that Odysseus came down within a mile or two of its target landing zone, a patch of relatively flat ground near a crater called Malapert A, Altemus added. The precise touchdown spot could soon become clear; NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter will snap photos of the area from above this weekend, if all goes according to plan.

The mission team will gather, and beam home, as much data as they can from Odysseus' new home on the moon. But the lander's electronics were not designed to survive the harsh cold of lunar night, so its days are numbered.

"We know at this landing site, the sun will move beyond our solar arrays, in any configuration, in approximately nine days," Crain said. "The best case scenario, we're looking at another nine to 10 days."