The Bank of England, the UK’s central bank, has raised its main interest rate by 0.5% to 3.5%. This is the ninth in a series of increases over the past year that have had a ripple effect across the economy.

A central bank rate rise feeds into the rates that banks, businesses and people are charged to borrow, but it should also boost savings rates. These rates can – and are – being affected to different degrees, however. In central bank jargon, this is called the transmission of monetary policy varying across markets. For instance, while mortgage rates have rocketed in recent months, deposit rates for many savings accounts just haven’t kept up.

Indeed, many major UK banks currently offer a rate of around 0.5% interest on savings held in a standard, easy to access account. Some accounts will pay more, of course, but savers may need to shop around and move accounts to get these rates.

Your bank typically holds some of the savings deposited by customers like you as “reserves” with the Bank of England. Historically, reserves were kept with the Bank of England for regulatory reasons – to ensure the bank has funds in case of surprisingly high withdrawals. More recently, the main reason is that the Bank of England pays interest on these reserves.

The interest paid to your bank on these reserves corresponds to the “base rate”, which is also referred to as the policy rate – now 3.5% in the UK. When you deduct the 0.5% paid to you in interest, this means a bank could make a handsome margin of 3% on your deposits. This is likely much higher than the marginal cost of servicing your account.

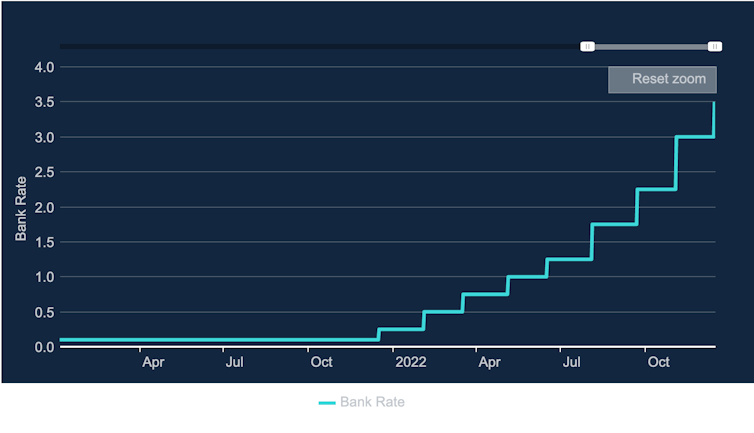

A year ago, the Bank of England base rate was 0.1%. And so, with deposit rates at or close to 0%, the deposit margins banks made at this time were minimal.

Bank of England base rate rises since January 2021

But rather than passing on rate increases made since to their depositors – as they have with loans and mortgages – some banks have been increasing their deposit margins on certain accounts, which generates money for their shareholders. These margins may rise further if interest rates continue to increase.

The Bank of England typically raises rates in order to cool down the economy and decrease inflation. Higher rates encourage people and businesses to save more and spend less, which is what tends to slow down inflation. But as deposit margins widen, the effects of such monetary policy weakens. When interest rates on deposits remain low, saving is less attractive and so people and businesses continue to spend and inflation continues to rise.

Bringing deposit rates closer to policy rates would strengthen this bond, reducing the overall increase in interest rates needed to bring inflation under control. Compressing the deposit margins that banks make is therefore in the interest of the central bank, and of the economy in general.

Central banks should pay interest on reserves

Many high street banks have accumulated a large stock of reserves over the past decade as a result of massive liquidity injections by the Bank of England during successive rounds of quantitative easing. For example, following the 2008 global financial crisis and then to keep the economy afloat at the height of COVID, the Bank of England bought government and corporate bonds to stimulate the economy, thereby boosting the amount of money in circulation.

Having used this tool multiple times over the past decade there is now a lot of money available to banks and so they often park any funds they do not lend out as reserves with the central bank. As explained already, these reserves earn the base rate.

Reserves are paid by the Bank of England, but any profit or loss it incurs actually belongs to the government – and ultimately the taxpayer. So, if the Bank of England was to pay a low, or zero, interest rate to high street banks instead, it would reduce the interest the government must pay on these reserves. Admittedly, this could discourage banks from holding more money in reserves and instead aggressively lend the money to businesses and households. But this would be inflationary, which defeats the purpose of rate rises.

Some former BoE officials have suggested simply forcing the banks to hold such reserves at a 0% rate, thereby saving the government billions in interest payments. But the Bank of England governor, Andrew Bailey, says this would affect the central bank’s ability to “steer the economy”. What the Bank of England needs now is for rates to increase, not decrease, to tackle inflation. In short, such a policy would help the government’s finances, but impair the Bank of England’s mission to tame inflation.

Banks should pass on interest to savers

What if central banks only paid high street banks interest for holding these reserves if they pass on rising interest rates to savers? This policy would improve the transmission of monetary policy, making the Bank of England’s job easier by reducing the overall amount by which interest rates would need to rise to bring inflation under control.

On top of improving monetary policy this would go some way towards protecting depositors from seeing the value of their savings eroded by inflation, alleviating the cost of living crisis. Compressing deposit margins would reduce bank profits. But there is no particular reason why bank shareholders – typically wealthier people that can better absorb the rising cost of living – should receive a windfall from the rapid increase in interest rates caused by high inflation while others suffer.

Frederic Malherbe does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.