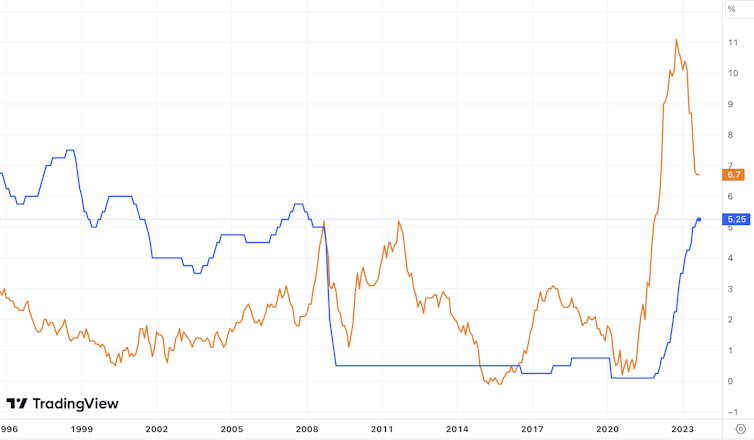

What next for interest rates? The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is widely expected to leave them unchanged when it meets on November 2, despite the fact that UK headline inflation is still at 6.7%. If so, it will mark the second monthly freeze in a row, following 14 consecutive hikes dating back to late 2021.

The main argument for pausing when inflation is still high is that each rise takes time to have full effect. It’s possible that the brakes have already been pressed far enough, and that any further rate rise could push the economy into recession. The MPC said as much in its rationale for the September hold.

While higher interest rates subdue inflationary pressure by reducing the amounts that people borrow and spend, households and businesses don’t feel the effect immediately. This is because they have either not borrowed or fixed their interest rates at a lower level. When those fixed-rate periods end, these borrowers will join the many who must already channel more of their income into interest payments, leaving less to buy other things.

The Bank of England (BoE) estimated in January that more than 1.4 million out of the total of 8.5 million mortgage borrowers in the UK would see interest rates jump during 2023, as they move off fixed rates that were mostly below 2%. Another 1.6 million are also expected to have to remortgage in 2024. Meanwhile, even debt-free businesses will find their income reduced as customers who need credit find it’s costing them more.

Alternative arguments

Additional pressures to avoid any further interest rate rises are now evident. Some economists doubt that raising rates has had much effect against today’s inflation because it has largely been caused, not by an overheating economy, but by scarcity of goods and commodities due to the Ukraine war and opening up after the pandemic.

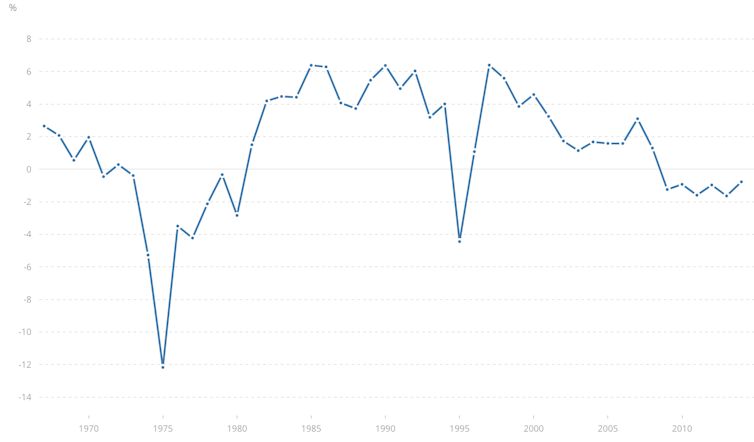

Still others point to evidence that rises in interest rates are followed by higher inflation. This has been found in recent studies of the US and Japan, and some lower-income economies such as Brazil and Indonesia. To understand this, you need to grasp a standard economic theory called the “Fisher effect”, named after an early 20th century American economist called Irvine Fisher. It suggests that economies have an equilibrium “real” interest rate, measured by the interest rate minus inflation.

For example, if a high-street bank offers one-year loans at 5% and annual inflation jumps from 3% to 5%, the bank has less incentive to lend at the same rate because the amount it gets back at the end of the year will be worth less than before. For the same reason, households and firms are dissuaded from saving. They are reacting to the fact that “real” interest rates have fallen. To keep lending and saving on track – in other words, to keep the economy running as normal – the central bank must raise the headline interest rate.

UK interest rate vs inflation

Some of this research also suggests there is a two-way causation. Not only do interest rates need to rise in response to inflation, they can also pull inflation upwards – precisely the opposite of what the monetary policymakers intend. This becomes a risk when interest rates are expected to stay high. Businesses then push up their prices, and households raise their wage demands, to cover their increased borrowing costs, and the expectation is fulfilled as central banks are forced to keep rates high.

Rate rises can still be effective if they reduce inflation quickly, allowing them to fall back to previous levels before expectations change. The International Monetary Fund, which often represents the economic mainstream, has conveyed the view that global interest rates will drop back to pre-pandemic levels once the present inflation wave has passed.

But other experts, including the Bank of England’s chief economist, Huw Pill, believe interest rates must stay elevated for a longer time to ensure inflation is crushed. Some even argue that they should now stabilise close to present levels, as a reset from the exceptional 13 years in which they stayed close to zero after the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

UK real interest rates

The risks of keeping interest rates at their present high level extend further than the possibility of causing recession, and worsening misery for the poorest borrowers, without taming inflation. A rise in interest rates means investors become more short-termist – increasing their focus on immediate costs and putting less value on potential gains further into the future. Especially when we need many billions of dollars of investment to build the green economy, a shortfall caused by high interest rates could have ramifications for the future of the planet.

Besides that concern, production capacity will only grow slowly across the board if investment is choked off. That is likely to be another source of inflationary pressure, if central banks don’t start to reverse the rise in interest rates early next year.

Alan Shipman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.