The year 2001 saw Barry Bonds hit 73 home runs, Roger Clemens go 20–3 and win the Cy Young Award, Enron CEO Kenneth Lay insist “there are no accounting issues” at the company, and Howard Gardner, a Harvard ethics professor, identify the decline of professional and academic integrity in his book Good Work.

Upon interviewing hundreds of students, Gardner and three researchers discovered a troubling trend. The students wanted to do good work and be successful, but they feared being disadvantaged because their peers were cutting corners. And so, as Gardner said, the prevailing attitude was, “We’ll be damned if we’ll lose out to them … Let us cut corners now and one day, when we have achieved fame and fortune, we’ll be good workers and set a good example.”

So concerned was the professor that he started reflection sessions on ethics at elite colleges. Students were thoughtful, he said, “Yet over and over again, we have also found hollowness at the core.”

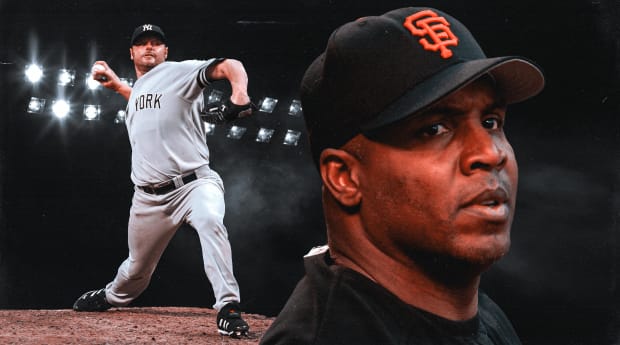

Geoff Burke/USA TODAY Sports; Mark J. Rebilas/USA TODAY Sports

Sound familiar, baseball fans and Hall of Fame voters? This era of atrophied ethics sums up the Steroid Era in baseball. Taking comfort in the company of rogues, ballplayers cut corners, though knowing the ethical breach most dared not admit it. They made money, broke records and cared not about the collateral damage they caused: the never-were and might-have-been careers of those who played cleanly.

(If you still cling to the absurd notions that “everybody was doing it,” “nobody was harmed,” or “steroids don’t make the player,” please read my 2012 story, “To Cheat or Not to Cheat,” on The Four Miracles, to understand how steroids made and broke careers and created an uneven playing field.)

Hall of Fame voting is one reckoning of the Steroid Era and the culture of “fame and fortune by any means.” With the class of ’22 results announced Tuesday, a streak that began in 2007 with Mark McGwire and Jose Canseco on the ballot is expected to remain intact: No known steroid user has been elected to the Hall.

Bonds, Clemens and Sammy Sosa are expected to end their 10-year run on the writers’ ballot without getting elected. Toss in McGwire, Rafael Palmeiro, Gary Sheffield, Andy Pettitte, Manny Ramírez and Alex Rodriguez, and the major known PED players are 0-for-63 on Hall of Fame ballots. A line has been drawn.

David Ortiz could be elected Tuesday but falls into a category of lesser evidence. Ortiz’s name, according to The New York Times, appeared on a list of positive tests in 2003 as part of anonymous survey testing with no penalties. But no substance was identified, and commissioner Rob Manfred and late union chief Michael Weiner, in unprecedented public defenses, both cited scientific questions as reasons not to consider it a positive test. Steroid users likely have been voted in already, but again, not with a preponderance of evidence.

The Baseball Writers Association of America is not a monolith. There are no back rooms where writers hatch plans to keep out steroid users. In fact, for the past six years most voters believe Bonds and Clemens should be in the Hall of Fame.

A majority is not enough. That’s the beauty of the process. Bonds and Clemens are being held to the same standards as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and Joe Jackson (just two votes in 1936). A player must receive 75% support to be elected. It’s always been that way.

For all the revisionist history and rationalizing, the past 15 years of voting is distilled to one truth: You can’t get 75% of voters to agree that steroid use should be honored. Bonds and Clemens picked up support as younger voters joined. A 33-year-old first-time voter, for instance, was in seventh grade when Bonds hit 73 home runs. But the electorate didn’t turn over fast enough for him to reach 75%.

Bonds, Rodriguez, Sosa, McGwire, Palmeiro and Ramírez are six of the top 15 home run hitters of all time. None have been elected. All began their careers between 1986 and '93. So did 18 other players who are in the Hall of Fame. As Henry Aaron said in 2009, “There’s no place in the Hall of Fame for people who cheat.”

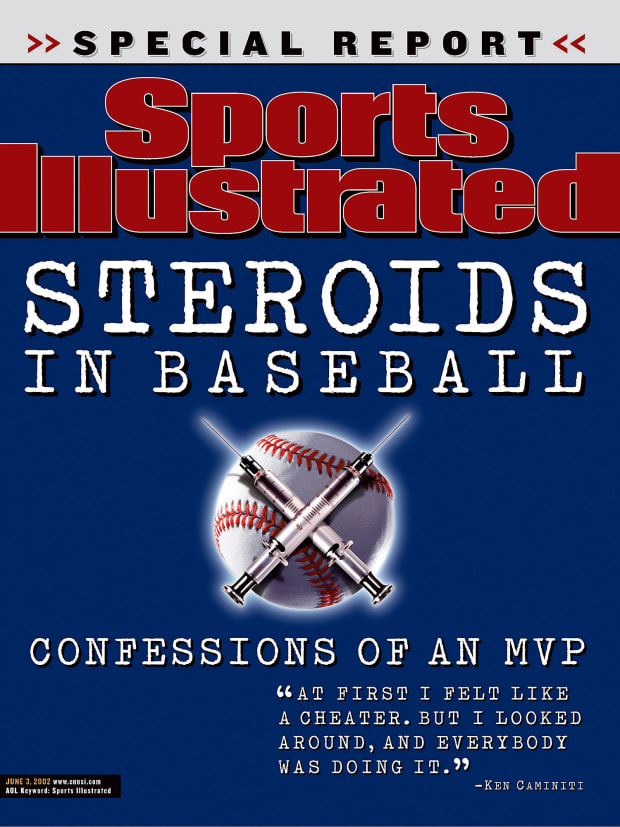

Until 1996, there had never been a season in which 12 players hit 40 home runs. Then it happened every year for the next six years. Then in 2002 I wrote a story in which Ken Caminiti detailed his steroid use and how rampant it was in the game. Suddenly Congress got involved and within three months players agreed to steroid testing. And since then, there have been no more seasons with a dozen players hitting 40 home runs.

James Porto

“I know what steroids did for me. It made me superhuman,” said pitcher Matt Herges, one of the few to admit it. “It made me an android, basically. Your body shuts down and the stuff takes over.”

Said pitcher Dan Naulty, “I was a full blown cheater and I knew it. You didn’t need a written rule. I was violating clear principles that were laid down within the rules.”

In 2004, Andy Van Slyke asked a question that should resonate just as strongly today: “It’s cheating. Why can’t anybody see that it’s cheating and it’s wrong?” Around that same time, Jeff Kent, who like Fred McGriff gets lost on Hall of Fame ballots because steroid users take up so much oxygen, said, “There should be more integrity in this game, and integrity is that you don’t cheat.”

McGwire is the rare cat who understood the cost of his choice. In 2012 he said, “It’s a mistake that I have to live with for the rest of my life. I have to deal with never, ever getting into the Hall of Fame. I totally understand and totally respect their opinion and I will never, ever push it.”

From 1996 to '99, McGwire averaged 61 homers, 133 RBIs and a .705 slugging percentage. McGwire never received more than 24% of the writers’ vote in his 10 years on the ballot. In one try on the Today’s Game Era Committee ballot, McGwire received “less than five votes” from the 16-person committee. He was dropped from the next ballot.

His lack of support, combined with the influence of late Hall of Famers such as Aaron and Joe Morgan who did not want to see steroid users enshrined, suggest Bonds and Clemens will do no better with the committee than they did with the writers. The same 75% threshold applies. The committee meets next in December.

Sign up to get the Five-Tool Newsletter in your inbox every week during the MLB offseason.

The end of Bonds and Clemens on the writers’ ballot marks a bend in the road, not an end, to how steroid users will be judged. Rodriguez, for instance, will be on the next nine ballots. But 15 years of voting history make a statement. Bonds and Clemens gained a boost in support in 2016 when 109 writers, mostly older, were dropped from the electorate. People began talking about how they eventually would be elected. It didn’t happen. The last 10% became a mountain too steep to climb.

We will never be done with it. Shoeless Joe Jackson was born in 1887 and Pete Rose in 1941 and you can start an instant debate today by bringing up their names and the Hall. So it will be for Bonds and Clemens.

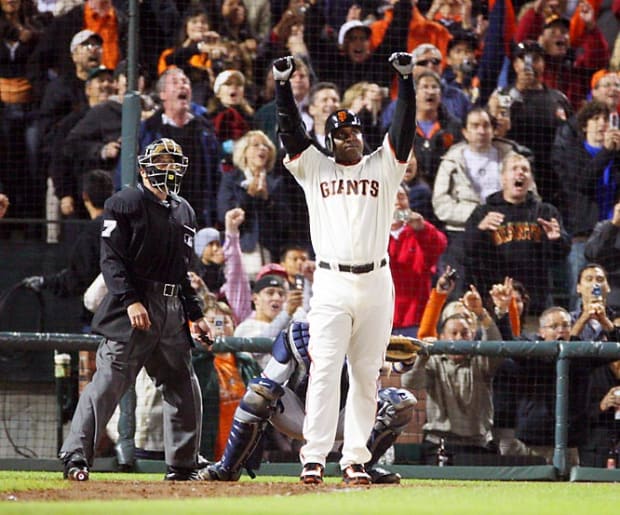

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated

But the angst of judging this era may dissipate, if only because of testing made possible by the honesty of Caminiti. Only two players who played in the majors last season were active in 2002, when Caminiti spoke up and made it the last season without PED testing: Albert Pujols and Oliver Perez.

Gardner, the Harvard ethics professor, is now 78. He is the son of German Jews who arrived in New York with $5 in their pocket on the night of Kristallnacht, which is to say they escaped just in time. They settled in Scranton, Pa. Gardner attended Harvard and never left, becoming a lifelong academic. He developed a groundbreaking theory that people have different kinds of intelligences, such as linguistic, mathematical, kinesthetic, and interpersonal, among others. “Intelligence” had never been considered plural.

As significant as Gardner recognized intelligences to be, he regarded ethics as even more important. What we do with our intelligences, not the aptitude itself, is what matters.

“I am fortunate to have the example of my parents, who were deeply ethical people,” he told The Harvard Crimson in 2018. “They did not do anything unethical; they wouldn’t even consider it. … I became interested in the purpose of our minds and our lives, in how intelligences and morality can work together to yield the kind of persons we admire and the kind of society in which we would like to live.”

Is professional ethics too much to ask, even in Hall of Fame voting? Not yet.