What happens to a cult of personality when that personality is gone? German lighting brand Ingo Maurer was forced to reckon with this question after its 87-year-old founder and namesake passed away in 2019. When Foscarini, the Veneto-based lighting brand headed up by Carlo Urbinati, purchased 90 per cent of the business in 2022, it began a new chapter for the Munich-based company, which for so long had been defined by Maurer’s larger-than-life persona.

Ingo Maurer: a poetic, whimsical approach to lighting

Born into a family of fishermen on southern Germany’s Reichenau Island in Lake Constance, Maurer studied graphic design in Munich before spending several years in the US as a freelance designer. He returned to Germany in 1963 and founded his company three years later. His first design was appropriately foundational: a conventional lightbulb set within a hand-blown lightbulb-shaped glass dome. He called it ‘Bulb’, and in 1969, it became part of the permanent design collection at MoMA in New York, kickstarting a long career that became more weird and wonderful as the years went on.

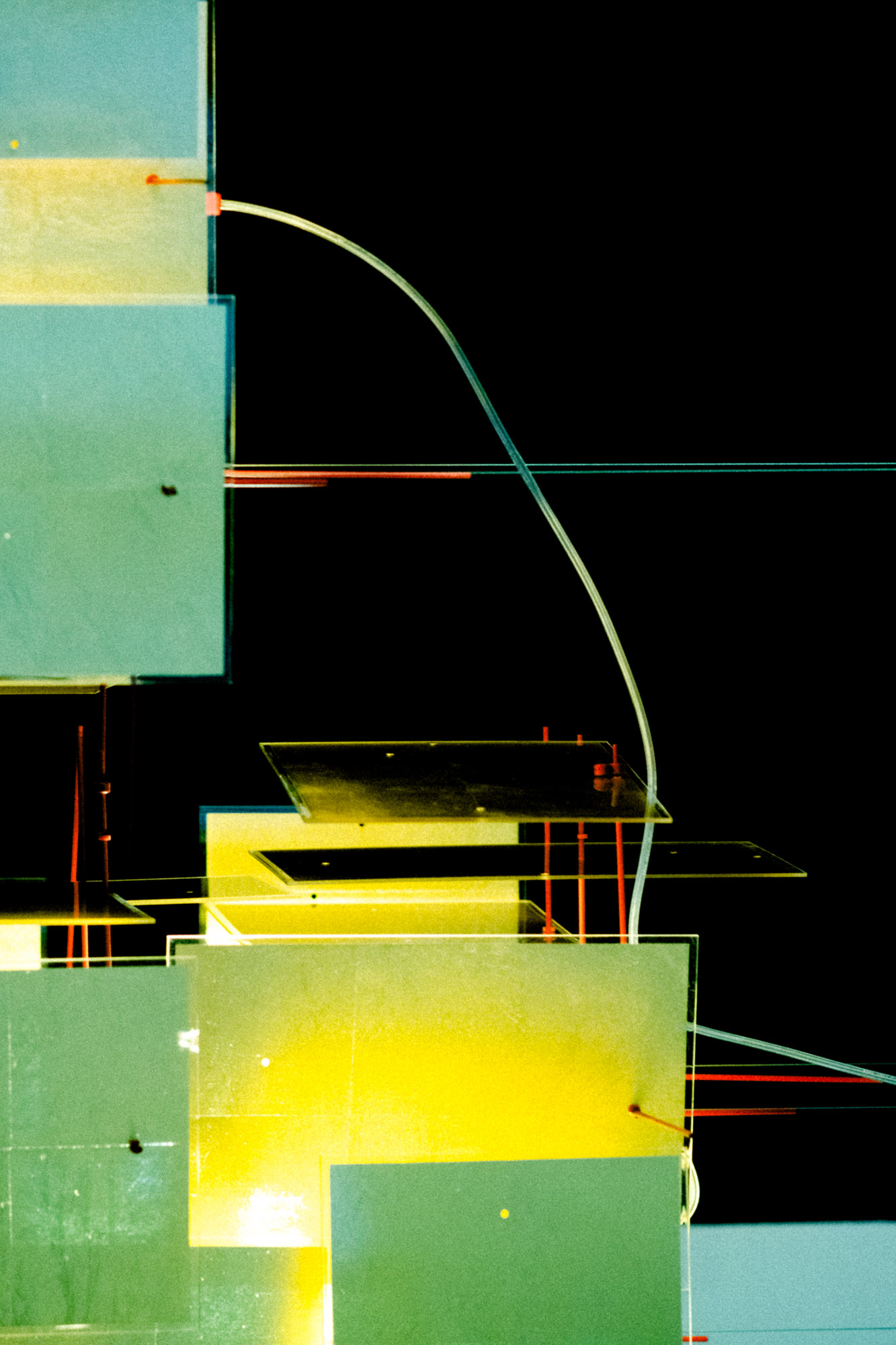

‘He invented in such a creative way,’ says Urbinati. ‘Nobody has ever matched it.’ He uses the example of Maurer’s 1984 ‘YaYaHo’ system, a low-voltage illuminated wire that can be strung with interchangeable elements. Maurer supposedly came up with the idea after observing local street lights while in Haiti over New Year. ‘Now you can find tension wire lighting in every catalogue. But he invented it. And it still feels very new.’

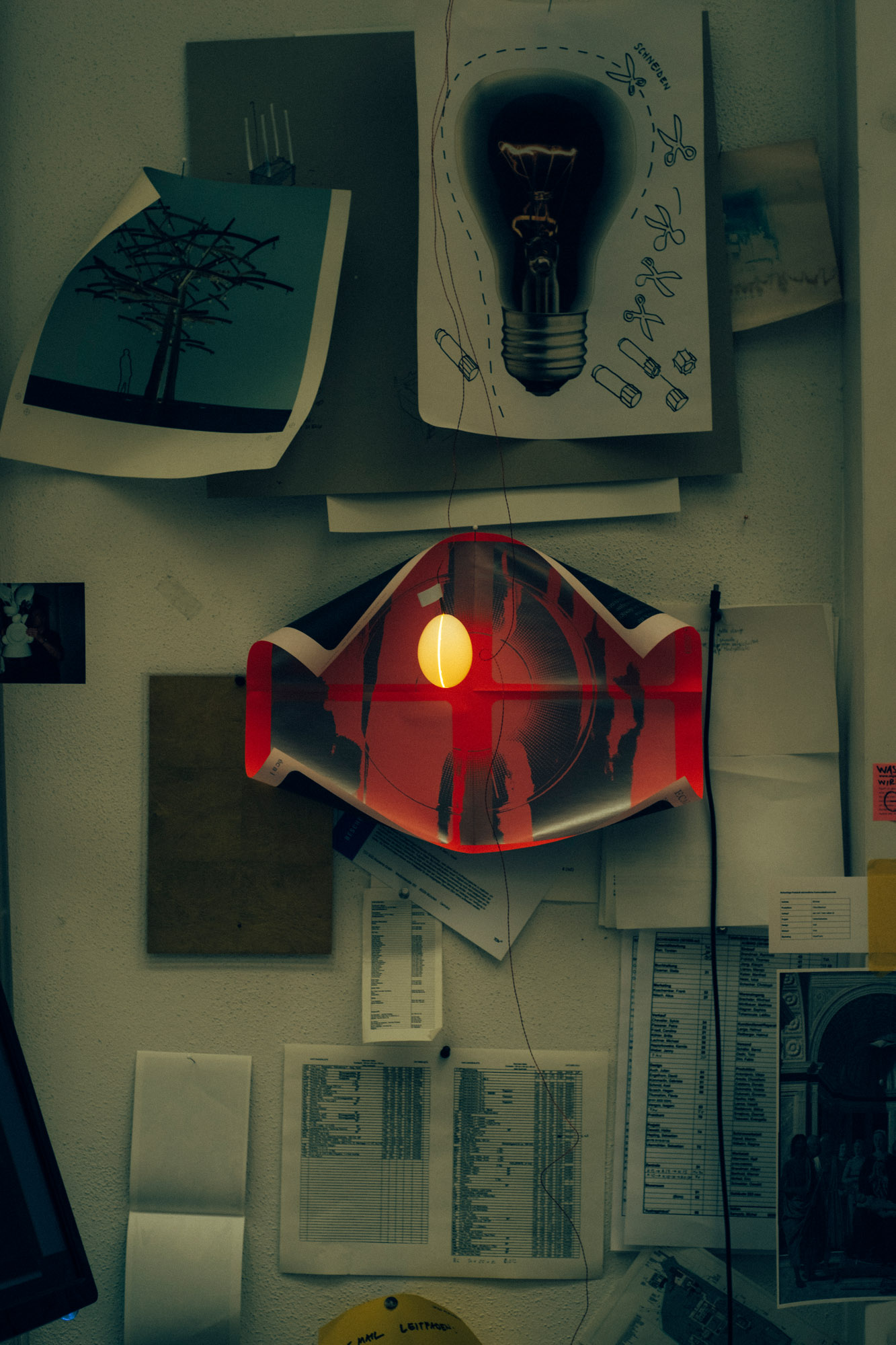

Maurer’s work was poetic, whimsical, even funny. His 2018 ‘Luzy’ pendant lamp, for instance, resembles a disembodied hand slipped into a blue washing-up glove with a naked bulb affixed to a finger, while one of his best known works, the 1970s ‘Uchiwa’ wall lamp, was inspired by his frequent travels. The simple Japanese bamboo fan is backlit and hung like a sconce, diffusing golden light instead of air.

But, as is often the case with visionaries, working with him could be a challenge. ‘I once made a drawing of the hierarchy at Ingo Maurer,’ says Axel Schmid, Ingo Maurer’s head of product and project design. ‘I made a dot for Ingo, a dot for Jenny [Lau, Maurer’s wife, who helped run the company until she died in 2014] and then a horizontal line underneath that represented everyone else.’

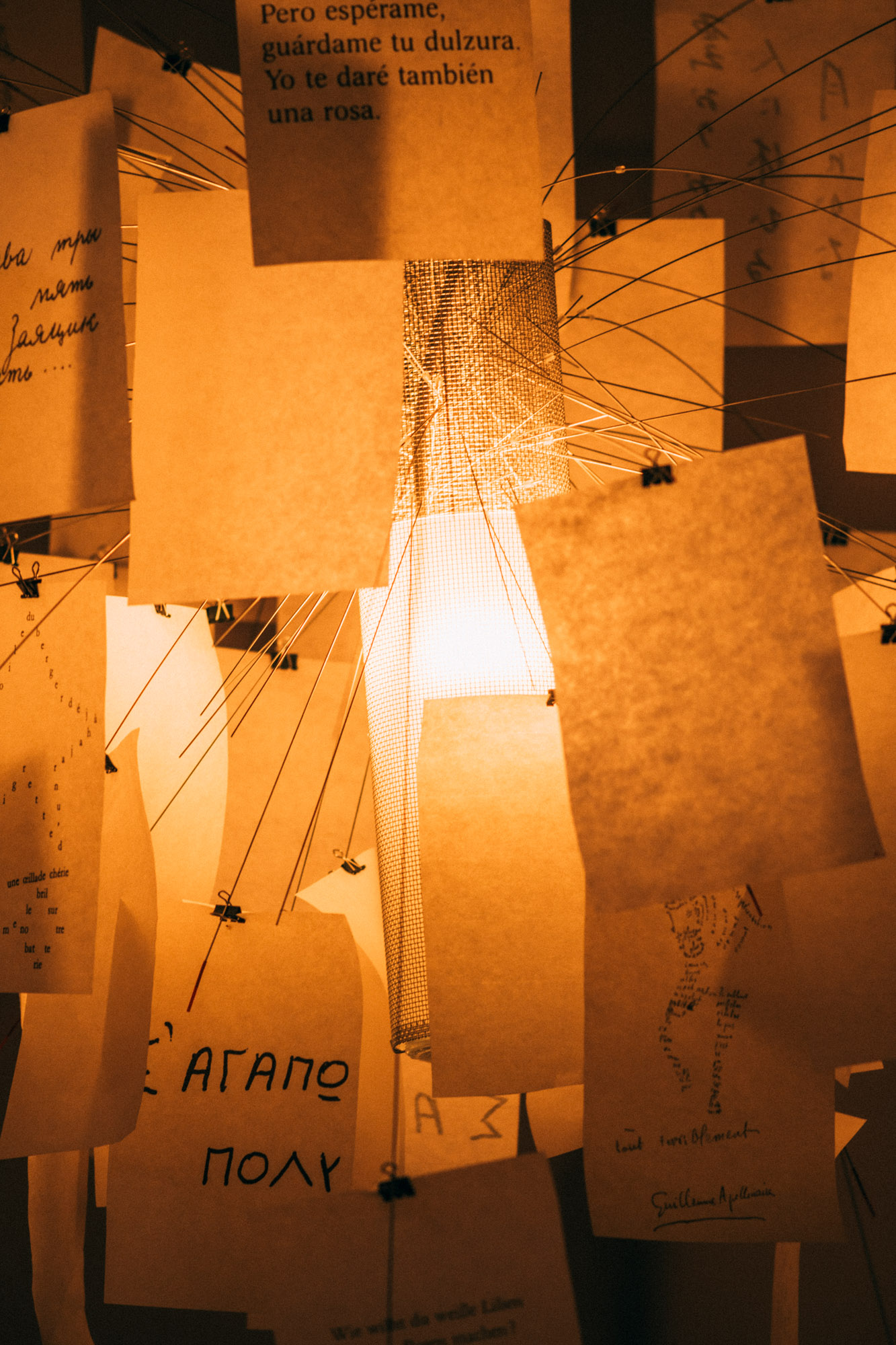

Urbinati puts it more bluntly: ‘Every time, it was the same story. Ingo would come back from Egypt or New York and throw some objects or technology on the table – things that probably had nothing to do with lighting – and explain why he was fascinated with them, then leave immediately for another trip. When he returned months later, he would select from three or four different prototypes. He’d ask the designer which they liked best and listen to their explanation. Then he would say – and this says a lot about him – yes, I understand your point, but we’re going with the other option.’ The arrangement, though challenging, worked well for the company while Maurer was still around. He may have always had the final say, but his approach fostered a culture of experimentation. When the design team was pushed to develop their own independent ideas and processes, it forced them to innovate. When two of Maurer’s designers, Dagmar Mombach and Hagen Sczech, were toying with the idea of working with textiles, Maurer urged them to look at paper instead for its superior ability to transmit light. ‘He put the designers in a room for an entire year to push the idea technically forward,’ Schmid recalls. ‘At the end, the pair opened the doors and said, “This is everything that’s possible with paper”.’

Their research would go on to become a cornerstone of the company’s portfolio from the late 1990s onwards. Maurer had already designed lamps in paper before – such as the crinkly, wide-brimmed 1980 ‘Lampampe’ – but Mombach and Sczech treated the material in an entirely novel way. Using artisan-made paper imported from Japan, they discovered that, if it were repeatedly crumpled and flattened, the sheet would eventually take on the consistency of a textile while retaining its strength. They were then able to manipulate the material like it was fabric. The sculpture-like ‘Kokoro’ (1998), ‘Poul Poul’ (1998), ‘Yoruba Rose’ (2017), and ‘Babadul’ (2017), as well as several other lamps, are all composed of elegantly draped paper finished with a plissé texture reminiscent of an Issey Miyake garment.

Maurer worked right up until his death. A few months later, the pandemic hit. The company was, understandably, thrown into unknown territory. Not only had the make-up of its organisation dramatically altered, so had the rest of the world. ‘It was a huge change for us. We were all working closely together like a family and suddenly everything switched,’ remembers Schmid. ‘So when the company was sold [by Maurer’s daughters Sarah Utermöhlen and Claude Maurer], it wasn’t a surprise.’ What was a surprise for many, however, was the buyer.

Foscarini and Ingo Maurer

Foscarini was founded in 1981 to produce Murano glass lighting for the contract sector. In the late 1980s, the brand shifted to producing for the consumer market, bringing respected designers like Rodolfo Dordoni and Ferruccio Laviani into the fold. Foscarini’s lights are sophisticated and minimal – worlds away from the tongue-in-cheek masterpieces that Maurer became known for. So what interest did the straight-laced Foscarini have in a brand like Ingo Maurer? For Urbinati, it was personal.

‘I used to run into Ingo all around the world,’ recalls Urbinati, who was a designer at Foscarini before taking over the company with his business partner Alessandro Vecchiato in 1988. ‘At different fairs and in New York – his apartment was only 50m away from our showroom.’ Urbinati even admits that he attempted to acquire the business in the early 1990s. ‘I knew its distribution wasn’t that strong and I thought it would be beneficial,’ he says. ‘But Maurer wasn’t interested in money.’

Urbinati stresses that, even now, his decision to purchase Ingo Maurer was not solely financial. ‘Ingo is someone I’ve admired my entire professional life,’ he says. ‘And the alternative was that the company might disappear.’ Since taking over, Urbinati has set about organising the shambolic structure and making sense of the company’s vast array of creations, starting with its catalogue. ‘It wasn’t really a catalogue,’ he says. ‘It was more like an artist’s portfolio.’ Foscarini’s directives have included conducting a broad audit of Ingo Maurer’s processes, standardising its technology (international and European lighting regulations have changed drastically over the decades), developing new products with the design team, and introducing the brand to a wider international audience. ‘The legacy and the heritage of what Ingo has left us is so rich,’ he says. ‘Our goal is to respect it and enhance it. Not to change or translate it.’

That mission brought them to the 2023 Salone del Mobile in Milan, where, in addition to Ingo Maurer’s usual booth at Euroluce, the company staged a Fuorisalone exhibition at Caselli 11-12, a contemporary gallery housed in a pair of 19th-century toll booths flanking the Porta Nuova city gate. This year, it’s planning to pop up at Base Milano in the Tortona district, where it will install a series of surreal illuminated sculptures across the building’s façade. While the brand will save new launches for the next Euroluce in 2025, it hopes to convert a new, younger cohort of Ingo Maurer admirers. ‘There are a generation of people who don’t know anything about Ingo Maurer,’ marvels Urbinati. As a longtime devotee himself, however, he is clear that this is not an issue at home. ‘All three of my sons grew up under Ingo Maurer’s lights.’