When Gareth Damian Martin started making Citizen Sleeper in 2020, as a solo developer with just one release to their name, they didn't expect too much. "I wanted to make something fast, in under two years, and something experimental. I didn't know if it would work," Damian Martin says. "Just before release, I really was convinced that it was a niche game, and it wouldn't do very well."

A decade earlier, Damian Martin had graduated into a recession, with a degree in puppetry. The next few years were spent bouncing between jobs, working on everything from theatre to QA at Sega – and in between, doing an awful lot of zero-hours contract work. They poured all of those experiences into a cyberpunk RPG in the truest sense, putting you in the shoes of an android Sleeper scraping by on the streets of the future.

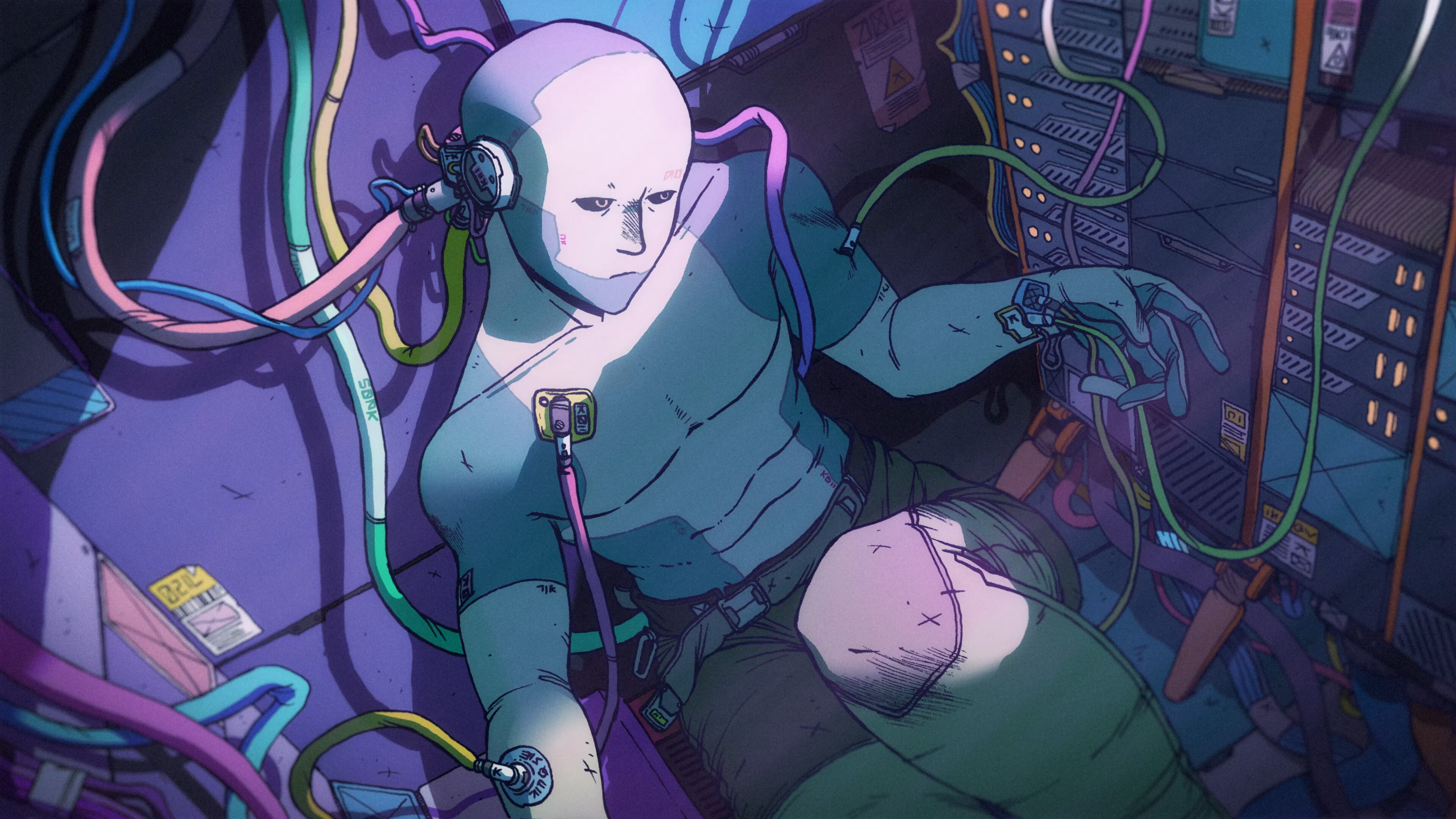

During the game's development, Damian Martin recruited two collaborators to help define the look and sound of that future. Composer Amos Roddy had worked on their debut game, In Other Waters, and returned to produce a moody synth soundtrack for the next one. Guillaume Singelin, meanwhile, was a French graphic novelist who'd liked In Other Waters enough to draw fan art for it, and who brought a cartoony lightness that complemented the grittiness of the new game's futuristic world. "They lifted each other," Damian Martin says.

The next frontier

There was an alchemy at work here, and perhaps it catalysed Citizen Sleeper's breakthrough success. On Steam, the game sold as many copies in its first week as In Other Waters had in two years – not counting the multitudes more who played it on Game Pass – and was nominated for three IGF awards and four BAFTAs. Another aspect that struck a chord with players: the plight of the Sleeper. A real human personality copied into a robot body as a way of creating cheap labour, you had to wrestle with your built-in obsolescence, taking any job available to pay for the Stabiliser that kept you from falling apart. It proved a pliable metaphor, resonating with personal experiences of everything from poverty to disability. "People have a strong relationship with it," Damian Martin says. "And I've got to respect that. I don't have… You know, I feel certain things about it, but I don't feel like those people do. Because to me, it's a knowable object. To players, it's a world – it's alive to them."

The experiment paid off, then, enough so that Damian Martin says others are already replicating its conditions: "In three years' time, you will see a lot of Citizen Sleeper-likes." That's part of the reason they're immediately returning to its world. "But also, I don't want to just walk away and leave it. I want to make sure I've fully explored this form." You might expect the game's success to push them towards expanding Jump Over The Age, their studio, but they're keeping development within the same tight bunch of collaborators. Still, there are some perks. While their previous games were made from home, or a shared office, today we find Damian Martin in a shiny new studio. Citizen Sleeper has brought a certain level of stability to the developer's life, it seems. And they've returned the favour to your brand-new Sleeper.

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

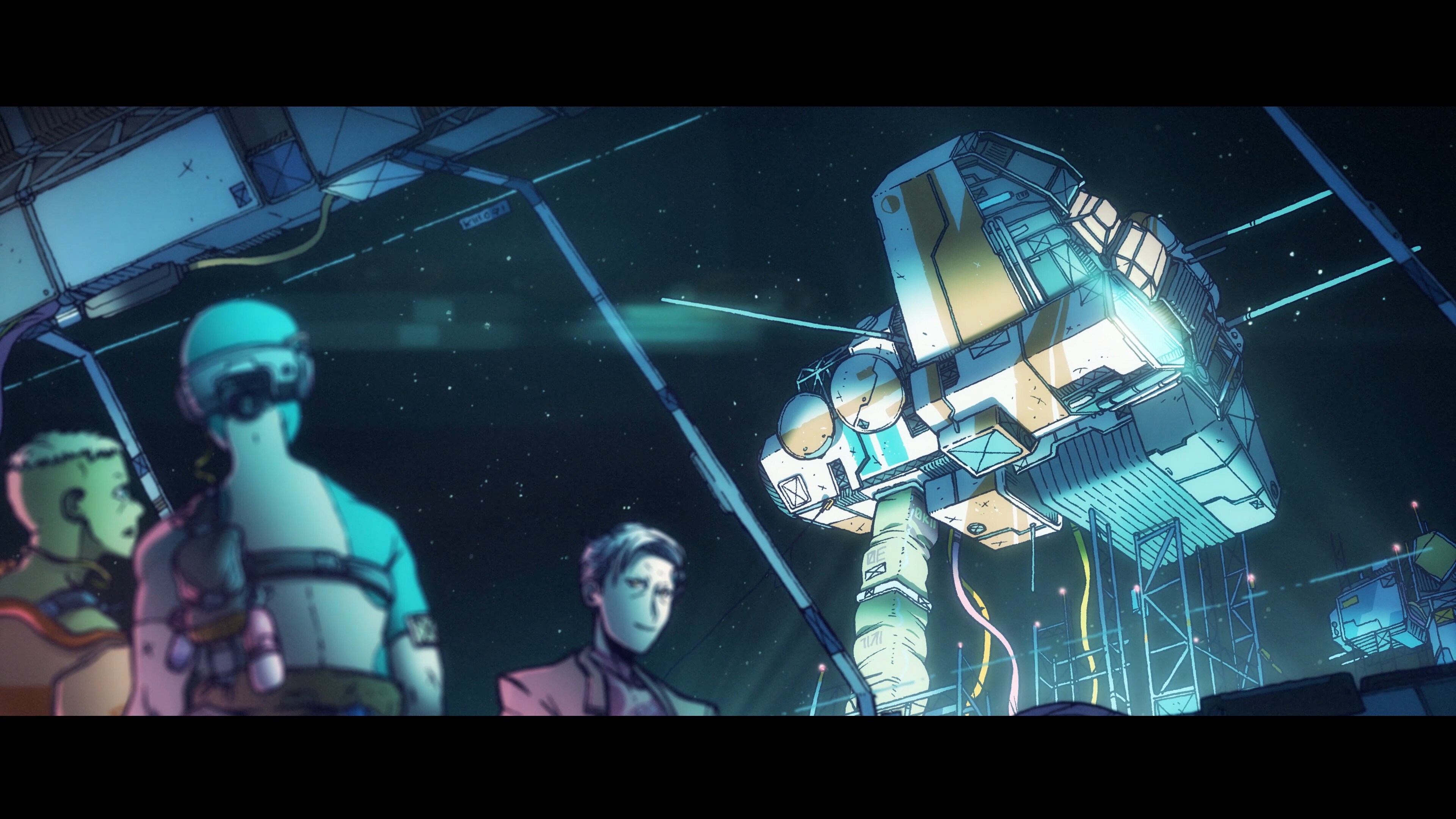

Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector leaves your original character where they were, living out whatever ending you might have found for them. The Sleeper you pick up with has a rather different life: no longer reliant on Stabiliser for survival (thanks in part to longtime companion Serafin), and proud owner of a spaceship. "It's not like the Starship Enterprise," Damian Martin clarifies. "It's more like having a canal boat." Still, it certainly beats waking up alone, inside a claustrophobic shipping container, as you did at the start of the original game.

"I wouldn't want to tell the same story again," Damian Martin says. "That's just not interesting to me – I have to spend every day of two, three years with this thing." So instead of urban science fiction, keying into their love of William Gibson, the model for Starward Vector is a "'monster of the week' sci-fi show". The developer rattles off examples: "Farscape, Firefly, Cowboy Bebop," all of them following the episodic adventures of a tight spaceship crew. "My feeling is that's never really been done well in games. Mass Effect 2 comes the closest, I think, but the problem there is that you're everyone's boss, so it's like a combination of that and The Office in space, where you mooch around and see if you can get a date from one of your co-workers." Rather than a workplace, Damian Martin wants Starward Vector to feel more like "flatmates in space".

If that all sounds a little freewheeling and carefree for the sequel to a game about the precarity of existence under capitalism, then there are a few extra details we should fill in about this new Sleeper. The game once again begins with you waking up – except this time, it's halfway through the surgery to excise your Stabiliser dependency. What happens next makes good on every warning about the dangers of rebooting a PC mid-update: your memories are gone forever, including any recollections of your closest friend. "Serafin has an existing relationship with the player," Damian Martin says – but you can no longer reciprocate. "It's up to you to decide, like, how are you going to be with him?" Meanwhile, that ship of yours? It's stolen, from your former boss. Who also happens to be a gangster.

And so you begin Citizen Sleeper 2 on the run. "It's good to have that propulsive energy behind you," Damian Martin says, "to push you down a path." Note the indefinite article there. Because while the original game stuck to a single location, the Erlin's Eye, Starward Vector opens up an entire asteroid belt of possible destinations and routes to you.

"Think of it like a fugitive movie. This is the first town they get to and are like, 'Oh, we're out of fuel'"

Your first stop, however, is fixed – and it's here, on the space station of Hexport, that our demo begins. "Think of it like a fugitive movie," Damian Martin says. "This is the first town they get to and are like, 'Oh, we're out of fuel'." Your ship has been damaged in the escape, a ruptured fuel line limiting your ability to travel. Hexport itself will look fairly familiar to anyone who visited the Eye: a 3D environment viewed from afar, peppered with hotspot locations where you can chat with the locals, spend some Cryo on supplies, or complete tasks. As is Citizen Sleeper tradition, every Cycle (essentially an in-game day) begins with you rolling a handful of dice. These represent your possible actions for the day, slotted into tasks with the number of pips on their face altering the odds of it going well or poorly.

In the first game, the number of dice you had to work with was based on your physical condition. A kind of persistent health bar, running from 'Stable' to 'Broken', it could be depleted by taking injuries, but also simply by existing, the built-in obsolescence of your robot body causing it to wear down day by day. It was a simple system that powered the "sense of inexorable decline" at the game's core, something that had to be constantly battled against. In retrospect, though, Damian Martin can see the shortcomings of this design. "It became predictable," they admit. "If you had a good supply of Stabiliser, as the game went on, you could feel increasingly comfortable." That served the thematic arc of your character, but while making the DLC chapters, the developer began to realise the limits of the stories it could be used to tell. "Because I made it quite quickly, and with a kind of minimum viable attitude, I ended up with this very simple dice system that works great but it doesn't expand well." And so condition has been ditched along with the Stabiliser.

"Condition implied damage," Damian Martin says. "I liked the idea of a resource that you could gain by trying to persuade someone of something, just as much as by using a welding torch to cut open an airlock." That resource is stress, represented in the HUD by a row of ten red lights, waiting to flicker on when things get too much. Every second light is marked with dice pips, from one to five; allow yourself to get that deep in the red, and any matching roll will be harmful. Not to your Sleeper, directly, but to that die, each of which now has its own dedicated health bar. That consists of three yellow dashes – empty them, and you'll lose access to the die permanently.

"You can sneak by on high stress. If you keep rolling high, you're safe," Damian Martin explains. "I'm trying to encourage this behaviour where the player is running on the edge of their capabilities at all times." After all, when stress is bubbling away at a manageable level, only one in six rolls will be any problem. Damian Martin is rolling a handful of physical dice on the desktop to illustrate the point: nice healthy fours and fives. Until eventually, inevitably – snake eyes. "You can end up damaging all your dice in one turn. And all of a sudden, you're in trouble."

In place of the inexorable decline, Starward Vector presents a boom-and-bust cycle, in which bright periods can turn dark without warning, leading to spirals that are hard to climb out of. The answer isn't cure but prevention – managing your stress levels by making sure your Sleeper has periods of downtime before things get bad. A new metaphor, then: "It's more like burnout, and long-term damage."

Next port of call

On Hexport, it's easy enough to keep stress on an even keel by balancing work with rest, in a rhythm more or less consistent with that of the first game. But now you're also always working towards something: your next contract, which Damian Martin describes as "very much like an episode in the 'monster of the week' format." Seen through that filter, your ship's ruptured fuel lines are a classic first-act setup. Visiting the local mechanic, Karsten, they turn out to be – surprise, surprise – very expensive parts to replace. But if we don't fancy paying the 500 Cryo, Karsten adds, he'd be willing to barter. Would we mind fetching him a data core from a nearby shipwreck?

Cue a heist-style preparation sequence. First up, supplies, which decide how many Cycles you have to complete the job before starvation kicks in. You're literally buying time, and not at a favourable conversion rate. "Supplies are very expensive," Damian Martin says. "So there's a big trade-off there." Then it's time to gather a crew. Each contract allows your Sleeper to take two allies, picked from the residents of your ship and any locals who happen to be looking for work. For this contract, one slot must be filled by Serafin. One of the other two options, Nia, is greyed out; we'd need to earn her trust first, Damian Martin explains, before she'll be willing to come along.

Instead we take Juni, a charming street-urchin hacker sort who actually approaches us about this job. She's certainly got the right CV, given her maxed-out Interface stat: good for hacking data cores and the like. This is one of the game's five skills, making their return in Starward Vector along with the starting classes that define them. This time, however, the differences are much more pronounced. "In the first game, you could pick up the other skills to flatten out your skill tree, basically," Damian Martin says. "You can't do that any more. And you're punished much more aggressively for not having a skill." On contracts, these shortfalls can be made up by your crew, who add their own dice to the pool.

There are, however, complications to bringing people along. Crew might have their own motives for taking the job, leading to unexpected narrative developments. And even when you're all singing from the same hymn sheet, there's the matter of stress to consider. Crewmates use a simplified version of this system, without any dice pips – a straight health bar, essentially – but stress matters more than ever when you're on a contract, since it can't be recovered until you're done. You've no time to relax when you're on the job.

There seems to be an awful lot of ticking clocks in play, even before we learn that contracts can have their own stress bars. Here, the shipwreck is falling apart around us, something we can slow down by sealing up a breach in the hull, but doing that requires spending dice – and also using up valuable time as you burn through supplies. Contracts are the dramatic peaks of the story, Damian Martin says, and it's not too hard to map the events of this one onto a TV episode structure, complete with guest stars, cliffhanger-friendly peril and a final-ad-break twist that we've been asked not to spoil here.

Vitally, though, this episode didn't need to play out as it did in our demo. "There are a few different ways out of Hexport," Damian Martin confirms. "It's important to me, even in the early part of the game while we're still tutorialising, to try and have opportunities for the player to be able to express [themselves]." We could have decided not to take this contract after all, and instead scraped together the cash by taking jobs from a contracts board – which may in turn have helped us build trust with Nia, opening up the possibility to take her on the data orb contract.

That change of personnel might have made things simpler, given what we learn about Juni aboard the shipwreck. Instead, though, we'd have had to deal with Nia's big brother back in Hexport, angry she was dragged along on such a dangerous contract, and insisting we pay half the earnings out to Nia as recompense. Assuming, of course, that we even managed to complete the objective, without Juni's hacker skills at our disposal. "In the original game, it was hard to have failstates," Damian Martin says. "But you can 100 per cent fail or, like, fuck up contracts – and that allows for these situations where you have to come back and deal with the consequences."

Mass affect

Space Missions going badly wrong and a wide cast of colourful characters who might join your crew on a more permanent basis? It's not hard to see why Damian Martin describes this sequel as "my Mass Effect 2". They admit to having a "conflicted relationship" with BioWare's series, but that just makes it grist for the mill. "I really enjoy the process of playing a triple-A game and being like, 'I'm gonna steal this, and I'm gonna do it better than they do'," they say. "Part of this is me looking at Mass Effect 2 and going, 'I love that game, but there's so many things about it that don't work for me'."

Their biggest target in this respect is granting your supporting cast greater autonomy. Crew members might well choose to hop off the ship at the next stop, and possibly stay there for good. "Your crew aren't just hanging around in the engine room, waiting for you to talk to them," Damian Martin says. "They're in the same place you're in, doing their own thing. And sometimes, after a few cycles, there'll be a scene where that crew member has done something." A mischievous smile. "I'm always trying to find ways to get you into trouble."

Your role on the ship, it seems, might well be that of responsible adult. "In Citizen Sleeper 1, you're very much an individual, and that affords you a certain kind of freedom, almost," Damian Martin says. "Whereas in Citizen Sleeper 2, you've taken responsibility for people." This is why you begin the game alongside Serafin, they explain. "Someone needs you to do the right thing, even when you don't know what that is. And then more and more of those people are going to come to you." Having your own spaceship (legal ownership be damned) makes you useful to other people – for transport, for shelter, for empowering them to work.

Thinking back on those zero-hour jobs that fed into the first Citizen Sleeper, and how it has changed its maker's life, we can't help but wonder if there's an element of continued autobiography at work here. "It does reflect a kind of change in my feelings, and in my life as well," Damian Martin says. It might be easy to suggest this very studio is, metaphorically speaking, the ship. But, of course, the developer has been careful not to make themself the captain of a crew here (a decision that's hard to argue with, given the results of the industry's recent expansionism) and they set us straight on that point soon enough: "Well, I mean, my house is the ship."

Which isn't to say that their concerns, making Starward Vector, are entirely domestic. Damian Martin describes a development ritual they've settled on over the years – one we first heard about in E369's preview of Citizen Sleeper. "I write on a Post-it note what the game is about, and stick it somewhere in my field of view. For In Other Waters, I wrote 'symbiosis'. For Citizen Sleeper, I wrote 'precarity'. For this one…" They peel the note from the corner of their monitor, and hold it up to show scrawled biro capital letters: 'CRISIS'. Below that is a later addendum: 'ENTROPY/NEED'.

It's worth noting that Starward Vector is set against the backdrop of a war, between the Conway and SenetStat corporations, but not actually in it. The asteroid belt you call home is "on the shore of the war," Damian Martin explains. "And no one knows when the war is going to come here, or if it will." It's a uniting concern of every character you meet in the game, we're told, their particular focus and urgency differing from person to person, just as it does in our own lives.

"People's psychological distance has a big effect on how they feel about crisis, and how present it feels," Damian Martin says. They're speaking from experience here. "A big influence is the war in Ukraine. My partner's Romanian – Romania is literally on the shore of the Black Sea. It's a place where mines wash up from the war." But that distance can be less literal: "If you talk to people about climate change, there are some people who feel that they're on the shores of that war."

Damian Martin is less interested in the nature of the crisis itself than how we process it, from a distance, and how it impacts our personal relationships. In particular, they want to dig into the idea that the closest bonds are forged in crisis. Questions of what we need from one another, and what we owe. These are enormous topics for any artist to tackle, of course, not least in a game that's expanding out in multiple other directions at the same time, but Damian Martin felt a responsibility to try. "Citizen Sleeper established this idea that, like, this is a game about now. I guess 'now' also changes over time. And so Citizen Sleeper 2 should continue to be about now – as opposed to being about five years ago or whatever."

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.