It’s just two weeks since the cast and crew at OpenAI decided to celebrate the first anniversary of last year’s launch of ChatGPT with the high farce of the did-they-didn’t-they sacking of its CEO Sam Altman.

It was all head-shakingly good fun. But before we move on, to understand what’s happening in big tech we need to keep our eyes on its bigness, not its tech innovation (much less its personalities). It’s the corporate interests of the large half-dozen or so companies that are shaping the digital transition.

With Altman returning as CEO and all OpenAI’s 700-odd staff back at work innovating around the same products as before, it looked like the only significant changes were the removal of employees (including Altman) from the controlling board of the not-for-profit and, in the very Silicon Valley “it’s a man’s world” kind of way, the two women board members were moved on and replaced by two, well, men.

But that sort of thinking brings too much of the starry-eyed celebrity residue of tabloid thinking to how we report the digital transition.

Follow the money to understand how the power of Microsoft’s US$10 billion capital investment has driven OpenAI from a research institute working “to ensure that artificial intelligence benefits all of humanity” to something more like a subcontracted skunk works, an industrial research lab with Microsoft as its dominant “when I say jump”-sized client.

Microsoft already owns 49% of OpenAI Global, the capped-for-profit subsidiary of OpenAI. Late last week, it was reported that the original and just about the biggest of the big tech companies would get a spot on the governing board, albeit as a non-voting observer.

Sounds like that inevitable shift of research interests is good for Microsoft, although the sharemarket shrugged it off, leaving the giant’s share price about where it was before Altman was fired. Maybe what’s good for Microsoft may be good for humanity… But as a for-profit corporation guided by the noxious concept of shareholder value, Microsoft is a poor stand-in for the interests of all the rest of us.

The change highlights one of the big Silicon Valley unknowns: can any of the individual big tech companies innovate themselves — and us with them — to a profoundly different future? Not from the look of things so far. Meta, for example, has spent more than US$20 billion to pivot its old standby Facebook to the metaverse, while Google has nestled itself into the broader “Alphabet” to innovate income streams (including big tech’s great white whale of the self-driving car).

OpenAI was set up with its not-for-profit open-source ethos by a broad grouping of Silicon Valley heavyweights as a solution to the distortion of innovation by individual corporate self-interest. Its soft launch of the third iteration of ChatGPT turned into the fastest-growing consumer technology in history with more than 100 million users in just a year.

Microsoft is integrating the technology into its Bing search engine. It forced Google to hurry on the release of Bard and encouraged Amazon to enter its own strategic partnership with the Open AI spin-off Anthropic.

Call it the innovator’s dilemma: these are companies that already make gobs of money — they’ve leveraged the opportunities of the internet to become the world’s top 10 companies. The best AI can do for them is help them stay where they are — while spending a lot of money on the way through.

Or call it enshittification, aka platform decay. “Here is how platforms die,” said Cory Doctorow. “First, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then they die.”

As with so much of the platform decay we experience every time we log on, expect the entropy of individual AI engines to be hurried by the AI crunching of consumer surveillance data to market and advertise things we may or may not want.

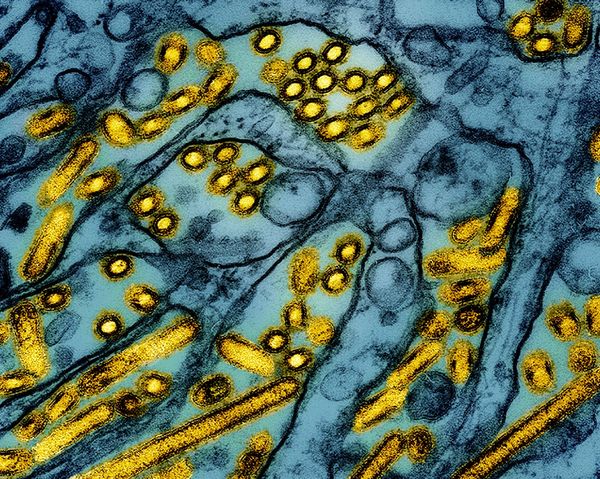

Or maybe — as COP28 should be reminding us this week — it’s environmental constraints. Artificial intelligence crunches data across multiple parameters, demanding extensive computing power (that’s why OpenAI needed something like Microsoft’s giant Azure server farm). That computing power demands electricity, constraining the diversity, size and application of generative AI platforms.

These challenges compound, as reports this week have suggested, to make ChatGPT “lazy” as it seeks to cut corners.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley boosters are talking up what OpenAI’s outgoing Australian board member Helen Toner recently called “the illusion of China’s AI prowess” (an article now read more for its veiled swipe at her then-fellow board member Altman for hyping the China threat as a pushback against regulation.)

The open-source chat interface of big tech platforms like ChatGPT (or Google’s Bard) is a key breakthrough in the continued remaking of our lives by artificial intelligence and machine learning. Can they overcome the distractions of corporate self-interest, the inevitability of platform decay and environmental constraints? Or should we expect the next big thing to come from somewhere else?