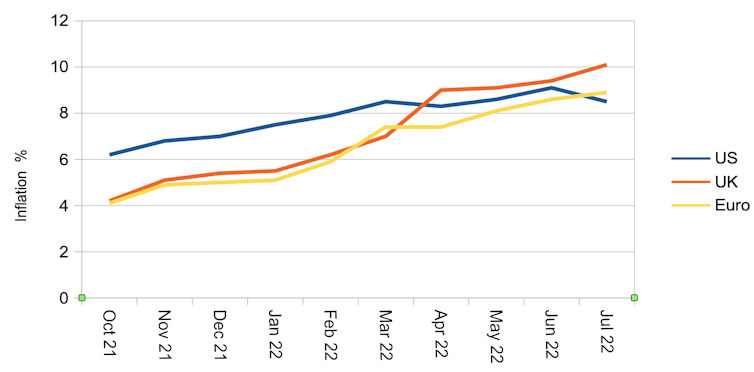

Inflation in the UK and eurozone is still getting worse. UK prices rose a whopping 10.1% in July compared to a year earlier, while those in the eurozone went up 8.9% – breaking longstanding records in both places. Contrast this with the equivalent data from the US a few days earlier, where the 8.5% rate was lower than the previous month and below market expectations.

While some analysts believe that US prices have now peaked, most think that the UK and eurozone, which are much more exposed to the effects of the Ukraine war, have a way to go yet. Even the Bank of England is saying that UK inflation will peak at over 13% later in 2022, before gradually returning to the 2% target level within two years.

UK inflation vs US and Europe

The prospect of more inflation is very bad news, since it reduces people’s real incomes and might also reduce investment, trade and economic growth. On top of that, the “cure” of raising interest rates can be harmful in its own right by making borrowing less attractive and driving down the value of everything from houses to shares.

But we also think it’s too optimistic to expect inflation to drop to 2% any time soon. More likely, we have entered a phase where various structural factors will keep it elevated for years to come.

Transitory inflation?

Until recently, central banks and the majority of economists and commentators attributed rising prices to temporary factors and claimed this would stop without much intervention. They mainly blamed logistic bottlenecks and production constraints due to the COVID-19 lockdowns. They also argued that as the cost of many products had been abnormally subdued during the lockdowns, it was inevitable that inflation would temporarily spike when prices returned to previous levels.

When prices started rising more widely and violently – which we predicted in a previous article a year ago – central banks and many economists started blaming the war in Ukraine and the elevated energy and food prices that came with it. But while all these factors have helped to drive inflation, they are not the whole story.

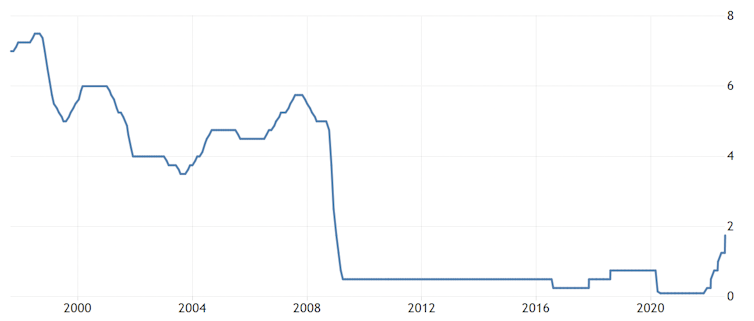

UK inflation 1997-2022

There is one clear cause of inflation that central bankers are not eager to advertise, namely the record low interest rates and expansion of the money supply through quantitative easing that they have been implementing since the 2008 financial crisis. In centuries of capitalism, we’ve never seen such low interest rates before.

UK benchmark interest rate 1997-2022

This ultra-loose monetary policy has created a backdrop of high demand at a time when production capabilities and the supply of cheap energy and imports have been disrupted. It has also pushed all asset classes – property, shares, precious metals, cryptocurrencies and so on – into bubble territory.

This has created record levels of inequality across our societies, while also further inflating demand by making people who hold these assets feel they can afford to spend more. Households as well as businesses have taken on cheap debt to finance properties and investments, or just to stay afloat.

Read more: Tinkering with the mortgage market won't solve the UK housing affordability crisis

Thanks to these high debt levels and high asset prices, central banks will need to tread very carefully when it comes to raising interest rates to combat inflation. Yet if they only hike interest rates a little, inflation will stay higher for longer.

Currencies, Brexit and globalisation

As far as the UK is concerned, the pound sterling is another factor likely to stoke inflation for years to come. It has already been weakening in comparison to other international currencies for a number of years, causing imports such as food, energy, cars and clothes to become more expensive.

There are numerous reasons to assume that this trend continues. Very aggressive interest rate rises in the US are making the dollar more appealing, which lowers the value of other international currencies. The chronic under-investment and consequent productivity gap in the UK compared to other G7 countries is another issue.

The pound also faces growing separatist sentiment in Northern Ireland and a looming second independence referendum in Scotland. Then there is Brexit. It is weakening trade with the EU and reducing business investment, both of which weigh on the currency.

There is also the looming prospect of a trade war with the EU. And incidentally, the loss of hundreds of thousands of EU professionals from the UK workforce is aggravating the nation’s longstanding skills gap. This is helping to make wages more expensive and reducing production, which will also lead to higher prices.

It should be said that the eurozone is also suffering from a weak currency. Alongside the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy in the US, the EU also has to bear the brunt of the Russian gas crisis and structural economic problems in countries such as Italy and Spain that have never been resolved. Although the pound’s weakness is worse overall, the euro is nudging US dollar parity for the first time in two decades.

Pound and euro values 2008-2022

Across the world, a final critical factor is the partial reversal of globalisation. According to Agustín Carstens, the head of the Bank for International Settlements (often described as the central bank of the central banks), this will increase product prices and keep inflation higher than it would have been for years to come.

There will be other factors that will counteract inflation. One is the retiral of the baby boomers, the largest generation ever seen, who will consume less as they stop working. Another is that technological advances continually increase productivity, which makes it cheaper to produce each unit. But with so many pressures driving prices up in the coming years, the overall likelihood is that inflation will remain stubbornly above central banks’ mandates of about 2%. This will have repercussions for consumption, profits, insolvencies and the stock market – not to mention economic growth overall.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.