Indonesians will go to the polls on February 14 in what is dubbed a “festival of democracy”.

They will be choosing not only a new president and vice president but also parliamentary and local representatives – in the world’s largest single-day election.

More than 204 million of Indonesia’s 270 million people are registered to vote, and while voting is not compulsory, election day is a public holiday so turnout is generally high – 81 percent at the last election in 2019, according to Indonesia’s General Election Commission.

There are 18 national political parties across Indonesia, with 575 parliamentary seats up for grabs.

The current Indonesian president, Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, has already served the maximum two terms in office, so this year’s election will mark the first change in leadership in 10 years.

Even Sembiring, the director of the Indonesian Forum for Environment in Riau (WALHI Riau) described the election as an “opportunity for healing” for Indonesian voters and “an important moment of potential to restore Indonesia for the next five years”.

However, some believe that whoever wins, it is likely to be business as usual in the world’s third-largest democracy.

“Given the relatively thin policy platforms of the three candidates and the fact that they’ve all largely pledged continuity, and been governors or cabinet members, it’s not a particularly significant departure from Jokowi’s platform,” said Judith Jacob, the director of geopolitical risk and security intelligence at risk management company Forward Global.

Here is all you need to know about the election.

Who are the candidates?

There are three presidential and vice presidential pairings vying for the top jobs including a former military general, a one-time academic and a self-professed “man of the people”.

Prabowo Subianto and Gibran Rakabuming Raka:

Prabowo Subianto is a 72-year-old former military strongman and Indonesia’s current defence minister. He is running for the top job for a third time, having lost to Jokowi in 2014 and 2019.

Prabowo has long been criticised for his time in the military and has been accused of, but never charged with, the kidnappings of more than 20 pro-democracy activists at the end of the 1990s, about a dozen of whom have never been found.

He has also been accused of human rights abuses in East Timor and Papua and was discharged from the military in 1998 and banned from entering the United States until 2020, after he became defence minister under Jokowi.

His running mate, 36-year-old Gibran Rakabuming Raka, is also a controversial candidate.

Gibran is Jokowi’s eldest son and was originally considered out of the running as he did not meet the minimum 40-year-old age requirement for presidential and vice presidential candidates. However, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court ruled last October that younger candidates could run if they had previously been elected to public office, a decision that cleared the way for Gibran, who is the current mayor of Surakarta, also known as Solo.

The decision was clouded by accusations of nepotism because the head of the court at the time was Anwar Usman, Jokowi’s brother-in-law.

Prabowo is the head of Gerindra, a nationalist, right-wing populist political party, and has the backing of a coalition of other parties including Golkar and the National Mandate Party (PAN).

Although Prabowo and Gibran do not have Jokowi’s explicit endorsement (the incumbent president is supposed to remain neutral), they are seen as the “continuity” candidates.

They have pledged to move ahead with Jokowi’s initiative to make Indonesia one of the world’s top five largest economies by 2045, as well as many of his infrastructure projects including moving the capital from Jakarta to the purpose-built city of Nusantara on the island of Borneo.

Prabowo has also said he plans to build three million new homes in rural, coastal and urban areas, and launch a free lunch programme for schoolchildren in a policy designed to combat stunting.

Ganjar Pranowo and Mahfud MD:

Ganjar Pranowo is the 55-year-old former governor of Central Java and is a member of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), a secular nationalist political party that backed Jokowi for the presidency in 2014 and 2019 and is led by Megawati Sukarnoputri, the daughter of Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno.

Ganjar is running with 66-year-old Mahfud MD, the former coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs, and the candidates also have the support of the United Development Party (PPP), the People’s Conscience Party (Hanura) and the Indonesian Unity Party (Perindo).

Ganjar and Mahfud have pitched themselves as two men of humble origins who understand the people of Indonesia.

They say they have travelled the length and breadth of the country to listen to the concerns of ordinary Indonesians, and have run a campaign based on improving their lives, partly through the wider distribution of social assistance under a programme known as KTP Sakti.

They have also pledged to raise salaries for civil servants, teachers and lecturers.

Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar:

Anies Baswedan is the former governor of Jakarta and is running as an independent and “opposition” candidate in the election. The 54-year-old was educated in the US, entered academia and later went into politics as education minister.

He sparked controversy when he ran for the governorship of Jakarta in 2017 and was accused of using identity politics against his rival Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, popularly known as Ahok, who ended up jailed for blasphemy.

Anies’s running mate Muhaimin Iskandar, 57, is the deputy speaker of the People’s Representative Council and the leader of the National Awakening Party (PKB), the largest Muslim political party in Indonesia. They are also backed by the NasDem party and another Muslim party, the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS).

Anies and Muhaimin are running on a promise to make Indonesia “just and prosperous” by, among other things, building 40 new cities across the country and cancelling Jokowi’s plan for Nusantara.

They have also pledged to promote equal opportunities for small business owners in order to create more jobs across Indonesia.

What are the main election issues?

As in many countries around the world, Indonesians’ main concern is the cost of living and being able to provide for themselves and their families.

Economic growth slowed to 5.05 percent in 2023 compared with 5.3 percent the year before, according to Statistics Indonesia, mostly as a result of weak exports and lower commodity prices.

With people under 40 making up about half the total number of registered voters, employment is a key concern.

According to Statistics Indonesia, the unemployment rate in August 2023 was 5.32 percent and the average monthly wage across Indonesia was 3.18 million rupiahs ($203).

Other issues include human rights and democratic decline in Indonesia, with student protests flaring across university campuses in recent weeks as staff and students at some of Indonesia’s largest and most prominent universities including Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta and Universitas Indonesia have spoken out about the need for fair and transparent elections.

“The student actions over the past few days have the potential to be Indonesia’s largest student protest movement since 1997 and 1998. There are more students and university leaders expressing their concerns and grievances during the current protests compared to the other protests,” Alex Arifianto, a research fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore, told Al Jazeera.

“The government has to be very careful in how it chooses to deal with the new movement, especially if it grows faster after February 14 if students become unhappy with the results.”

How does the election work?

Come February 14, polling stations across Indonesia’s three time zones (GMT +7/8/9), will open at 7am and close at 1pm.

All voters over the age of 17 will be given five different ballot papers to choose presidential and vice presidential candidates, as well as representatives at national, provincial, regional, and regency and city levels. Depending on the area, some polling stations are likely to see long queues as voters turn out early in an effort to escape the searing Indonesian heat that builds throughout the day.

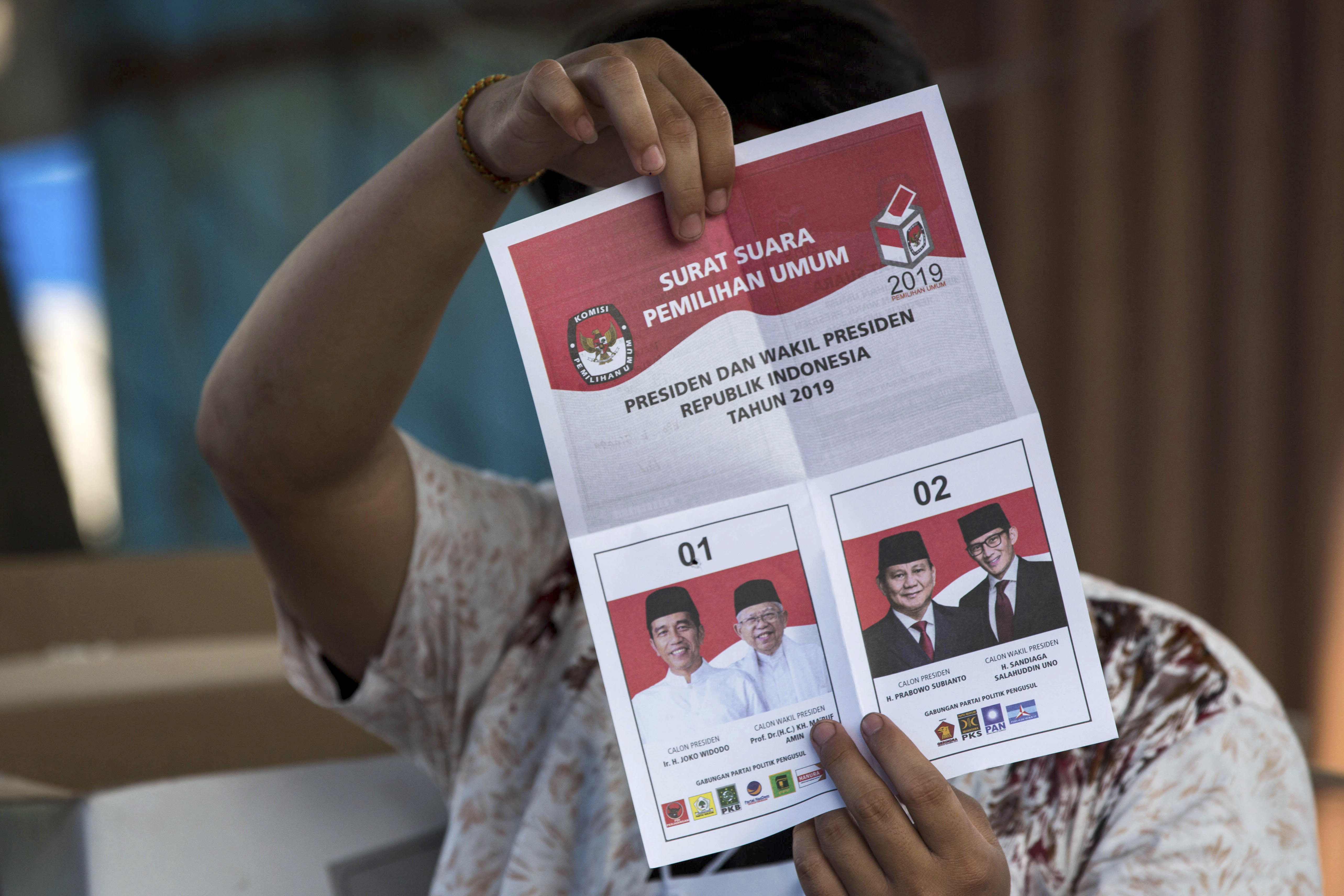

In the voting booth, people make their choice by piercing the ballot paper with a nail in a process known as “coblos” which means “to punch”. It is felt that using a nail to punch a hole in the ballot paper makes it harder to manipulate votes.

Votes are counted in public at polling stations, with the paper ballots held up so everyone can see the light shining through the pierced hole as the names of the chosen candidates are read aloud. Once they have voted, every voter dips their little finger in indelible ink to guard against casting multiple votes.

“The anatomy of the sheer numbers of voters involved makes the Indonesian election the largest one-day election in the world,” Titi Anggraini, an advisory board member of the Association for Elections and Democracy and a constitutional law lecturer at Universitas Indonesia, told Al Jazeera.

“The combination of simultaneous elections with an open proportional system which is carried out manually also makes the Indonesian election one of the most complicated and complex elections in the world.”

The process at the polling stations will be overseen by about seven million election officials and independent workers.

In 2019, more than 890 election workers died following the exhaustive polls.

When can we expect a result?

There are more than 820,000 polling stations across Indonesia, an archipelago made up of some 17,000 islands, and the count starts as soon as voting closes.

Many polling stations use a “quick count” – based on a sampling method – to give an early indication of where things are headed.

A preliminary result from the elections commission is likely to be announced on the evening of February 14, but the official result could take as long as 35 days. Much depends on whether the vote is close.

Any legal complaints by any of the candidates involved, including the three sets of presidential and vice presidential hopefuls, will need to be filed within 35 days of the election.

On his previous two outings, Prabowo challenged the result through Indonesia’s Constitutional Court.

In 2019, the legal challenge and accusation of vote rigging and ballot tampering sparked violent protests across the country that left nine people dead.

Who can vote?

Any Indonesian citizen who is 17 or older can vote.

About 52 percent of registered voters are under the age of 40, and about a third of the total are under the age of 30, making the “youth vote” an important one.

This year, 49.91 percent of registered voters are male and 50.09 percent are female.

Members of the Indonesian police and the military are banned from voting.

What happens after February 14?

Presidential candidates need 50 percent of the overall vote and at least 20 percent of votes in each province in order to claim victory. Political parties need four percent of the vote in order to enter parliament.

According to many Indonesian pollsters, Prabowo is leading the polls, although he continues to hover close to the 50 percent mark, meaning that he may not be able to claim an outright win in the first round.

If no single candidate passes the 50 percent threshold, the top two candidate pairs will go into a second and final round on June 26.

The new president will be inaugurated in October.