Shot in luminous black and white, the Australian Indigenous mystery “Limbo” takes place in the Outback, in a town called Coober Pedy, a place that often resembles the moon. There are craters and caves, and the “Limbo” motel rooms look otherworldly. It is here that cop Travis Hurley (Simon Baker, "The Mentalist) finds himself analyzing a 20-year-old case of an Aboriginal girl’s disappearance to determine if it should be reopened.

Travis tracks down the girl’s now-adult siblings, Charlie (Rob Collins) who is reluctant to talk with cops after being a suspect at the time of the crime, and his estranged sister Emma (Natasha Wanganeen), a single mother raising three kids. Both are wary, but eventually cooperative as Travis finds himself stranded in the town after having engine trouble.

“Limbo,” directed by Ivan Sen (who also wrote, edited, and did the phenomenal cinematography), is a low-key thriller. It is as much a character study of Charlie and Emma grappling with the compounded trauma of racism as it is a case study of Travis, a flinty, burned-out cop who listens to evangelical radio in the film’s first scene and then shoots up heroin in his hotel room in the next. Baker is terrific here, listening and observing all the folks he meets, shifting from reluctant cop to someone who becomes invested in the lives of the people he meets. A scene where Emma asks Travis to talk to Zac (Mark Coe) the young boy she is raising who is not her own, is quite revealing.

Sen does not hurry his film along, letting viewers absorb this atmospheric environment much like Travis does. It is an effective, slow-burn crime drama that has a potent ending. In separate interviews, Sen and Baker spoke to Salon about making “Limbo.”

Can you talk about the look of the film? The emphasis on space and the composition of the visuals which depict isolation is very distinctive and atmospheric.

Ivan Sen: When I write a story, everything grows from the location — the characters, the visual style, the camera style, even the editing. That Coober Pedy location has 6 million holes in the ground created by the newcomers to the land, after colonization. The Europeans dug holes in the ground that has an ancient history. This otherworldly feeling is present within every frame of the film, and Travis who finds himself in this landscape is like a space traveler.

Simon Baker: We shot this film in a mining town where people live underground because the daytime temperatures are extreme. It’s a pockmarked landscape. It’s a place where people come in, drill holes, and if they find anything they explore it, or they move on and drill another hole over here. It is a beautiful landscape completely destroyed by human intervention and greed. They want [to mine] opals, a shiny object that has zero practical purpose, other than being something pretty.

Ivan, why did you choose to shoot in black and white? Was it to reflect the differences between the characters or the gray morality?

Sen: I was initially thinking of shooting on color film, but it is difficult to shoot on film in Australia. I didn’t feel that digital color was right for this story. I wanted a nostalgic, living in a memory type of film. It’s people living in a memory. These families have been living in the past, this limbo, as has our hero [Travis]. The absence of color allows you to concentrate on the story and the characters. The colors out there are quite strong and emotionally can distract you.

What decisions did you make in how to tell this story? It unfolds slowly, quietly.

Sen: I wanted to portray this case review as a very realistic one. I talked to detectives, and this is the reality of crime-solving 20 years after the fact. The chances of revealing any new information are really very low, and the chance of solving this case is much lower than that. I wasn’t going to push this into some Hollywood reality of solving a crime. This reflects the reality of my family and the reality of many Indigenous people in Australia, who have been victims of crime and had to deal with the lackluster police follow-up because it is involving Indigenous families. That has been passed down since colonization and is still part of the fabric of Australia.

Travis goes about his work in a rather laconic fashion. Is he a burnt-out cop or a cynic or does he have justice in mind?

Sen: I modeled his character after some real-life police officers that I know. The apathy that Australian police officers have towards Indigenous Australians is highly prevalent. I wanted this character to have that. Because of the apathetic approach to the case 20 years ago, Travis is not that different. He is not going to roll into town and solve everything. That’s unrealistic. It’s in line with my view of the situation involving Indigenous Australians and the justice system. The cops are as flawed as everyone else, even more so in some cases.

Baker: What I like about the film is that it sits in the gray. In a way, Travis is trying to redeem himself. The idea that he has self-isolated through his own traumas made it easy for him to access this story of this family being isolated through the neglect of the justice system and him being a part of that neglect as well. The generosity of the family and the grief they live with from day to day opens him up a bit. In essence, they help save him, and they show him a sensitivity and an openness and a generosity and a kindness, and he projects that back on to them. I liked the idea of all these broken people reaching for something.

The film addresses the racist treatment of Aboriginals by the police. Can you discuss the idea of authority in the film and the exploitation/abuse of Indigenous folks by those who colonize them?

Sen: I often talk about how the justice system and its relationship with Indigenous Australians is reflective of the wider society of Australia. This apathetic approach to Indigenous Australians permeates all of our government departments and mainstream society. Indigenous people rarely make it into the headlines. Last year we had a national referendum allowing Indigenous people to be recognized within our constitution. It was a met with a resounding “no.” For Indigenous people it was not only a slap in the face, but a kind of a survey to see where we were at as a country. The justice system is only one fragment of that attitude towards Indigenous Australians. When you make art about this stuff, hopefully, it does go on to have some influence.

Baker: There are situations like this going on all across Australia, and there are similar cases in Canada with crimes against Indigenous women. The lack of faith and trust in the justice system because of the years of misconduct towards First Australians is rife. What I did like about this film and the character in regard to race relations, is that there is a forthrightness to Travis. There’s a scene where Charlie says to Travis, “You don’t like Black fellas,” and Travis says, “No, I don’t like too many people. And they don’t really like me.” He has had a few bad run-ins in the past. I love how he doesn’t sugarcoat the “I’m not a racist” aspect. There is a frankness to it. He hasn’t had great experience with Indigenous Australians. It sets up, between those characters, a relationship that is founded on honesty. The strong relationship is between those two men.

What did you think about the ending?

I think it’s a bit cynical and powerful, but we can’t talk about the ending!

Baker: There was a Q&A in Sydney, and a young lady asked about resolution and if the audience is owed a resolution. But that is an audience member looking at it as a film. Ivan, who is an Indigenous filmmaker, said in response to the lack of resolution, “We’ve come to realize in films that we want a resolution, and we expect that we deserve one, or are entitled to a resolution, but in my family and my people, we live constantly without a resolution.” That’s really the essence of what the film is about. What is justice for First Australians subjected to a long, violent, and protracted colonization? And still, in 2023 we vote against a referendum suggesting that Indigenous Australians should be enshrined in our constitution and have a voice to speak on their behalf for themselves in parliament.

Simon, what does it mean for you to take roles in films like “Limbo” after achieving success in Hollywood? This is very far removed from some of your heartthrob roles.

Baker: I’d much rather do this. [Laughs] I had a great run in the States as a younger man. I had a family and I'm working to provide for my family. You get older and develop a bit more character and understand who you are and see more things and reach deeper in characters you get to play. I am fortunate. I come from Australia, and we have a small film industry and compelling, interesting, cross-cultural stories to be told and we know how to do it inexpensively. The process and business of filmmaking in this country is less a business and more of a cultural exploration. I took myself out of Hollywood for a while. I made my own film over here, and then I did “Limbo” and the Netflix series, “Boy Swallows Universe.”

And Ivan, what appealed to you about working with Simon?

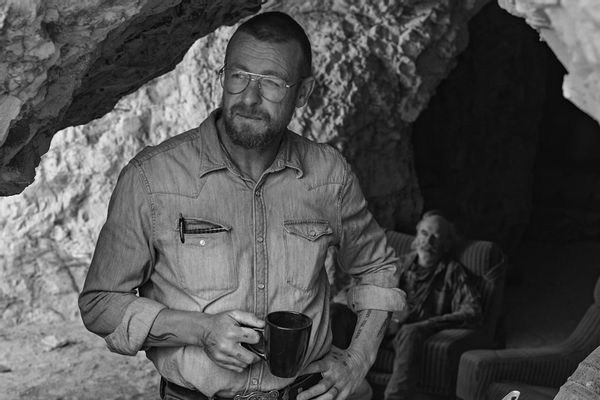

Sen: His excitement right away was a good sign. We moved forward to develop the character. My main thing initially with Simon was to change his appearance. He was quite well known for a certain appearance, and I wanted to knock that on the head and change that and make him almost unrecognizable. Doing that introduced traits to his character, like shaving his head, the tattoos, the Christianity connection. All that came through immediately as he agreed to do the film.

Baker: The character evolved from the early script where Travis was a diabetic. We explored that and took it a bit further — the escapism of heroin. That’s his medication, and I liked to see a somewhat functioning heroin user. He was not a flat-out extreme junkie. We played around with what he was listening to. I said to Ivan, "There is a bigger picture of looking for something else to redeem and attach to," and that religious idea was born out of that.

Do you think “Limbo” is a redemption tale?

Baker: I wouldn’t categorize it as a redemption tale. Is he a good guy or a bad guy? It’s interesting because of all the countries in the world, Americans attach themselves to “good” or “bad.” They want to know if it’s a good guy or a bad guy. I don’t know that actual good guys or bad guys exist. There are people who do wrong, and make bad choices, and get caught in a cycle of that who also love and care and have compassion for at the same time. I think it’s far more complex in our world. I think sometimes a character like Travis has a self-perpetuating negativity. The idea of making mistakes, then pile on top of that self-loathing, and suddenly you are in a cycle of negativity. The way you see yourself is as a piece of sh*t. It is pretty much where that guy exists — so uncomfortable within himself that he wants to be anywhere else.

Sen: There is an element of that within Travis, and also a sense of it with other characters as well. In some strange way, all the characters get a sense of redemption — even the suspect.

“Limbo” opens March 22 in New York, with a wider national expansion to follow in select markets.