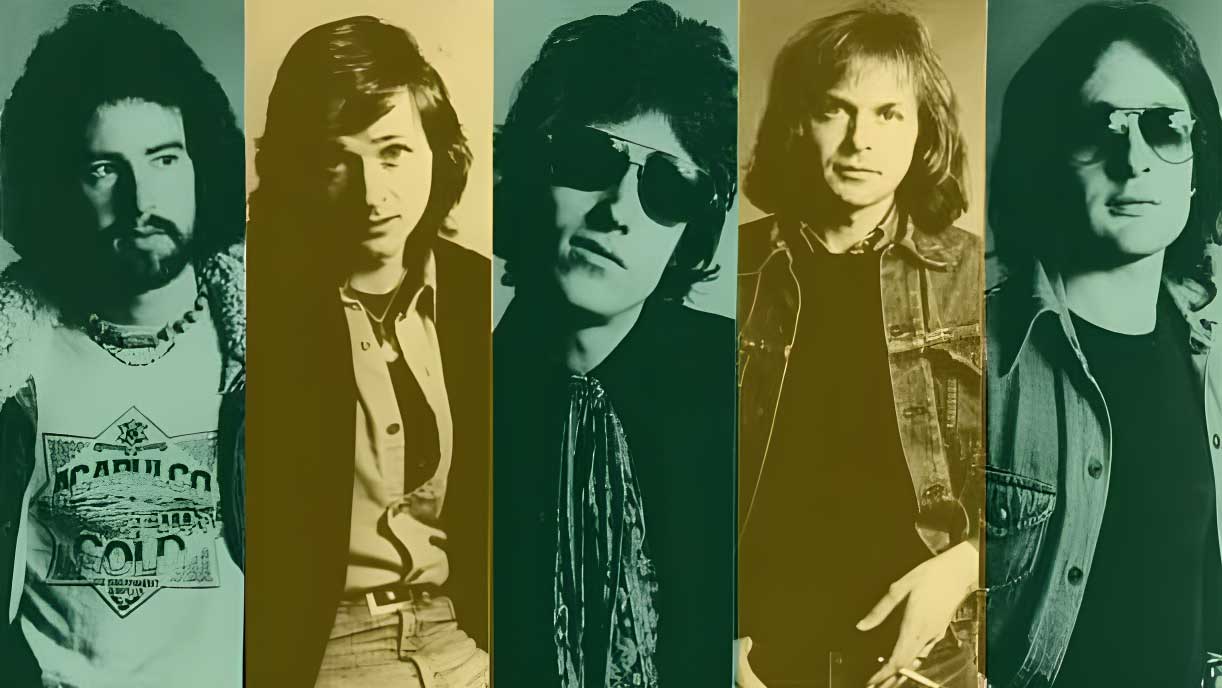

Aussie Legends The Angels are currently on their 50 Years In The Making tour, celebrating an often fractious half century in which their biggest songs have become much-loved Aussie standards. In 2014 Classic Rock spoke with three of the band's most famous members to get their story: brothers Rick and John Brewster, who remain with The Angels until this day, and much-loved former singer Doc Neeson, who died just a month after the interview.

The Angels were no strangers to unruly audiences, but the 100,000 revellers who’d gathered on the steps of the Sydney Opera House on December 31, 1979 was a beast that even they couldn’t tame. The first indication of the crowd’s mood came when the city’s Lord Mayor was bottled off before he could complete his New Year’s Eve address. Then Rolf Harris, if you can believe it, received the same treatment – perhaps showing some foresight on the part of the crowd.

As The Angels – who were huge in Australia – started playing their live-wire yet cerebral boogie, a crowd surge sent dozens of people scampering onto the stage to avoid being crushed. Rather than usher the frightened punters into the wings, security tossed them back like undersized fish into a furious sea.

“We’re starting to get a little nervous,” recalls guitarist John Brewster. “A broken bottle went flying past my head and embedded itself into the cloth of my guitar amp.”

As the band played one of their biggest hits, Marseilles, Brewster heard a thud. Bassist Chris Bailey had just been struck on the head by an empty champagne magnum and was unconscious before he hit the deck. Seconds later a missile struck explosive vocalist Doc Neeson and he too was thrown to the floor. As the band scurried for cover, their sound man, Howard Page, patched himself into the PA and admonished the crowd: “See what you’ve done, you idiots!” he roared.

“We felt like lambs to the slaughter,” Neeson reflected in May 2014, “sacrificed on the steps of the Opera House.”

In living rooms around Australia, shocked families viewed the live broadcast with mouths agape. The network cut to an ad break. When coverage resumed it was as if nothing had happened.

“They went: ‘Oh well, that was New Year’s Eve. All the best for the New Year,’” Brewster says with a laugh, speaking today from his home in Adelaide. “It was quite possible that Chris and Doc being hit shocked the audience, cos there was this eerie lull and people quietly walked away. But it could have escalated into something really serious – I’m talking death.”

Forty years after they formed and 35 years since that New Year’s Eve debacle, the spectre of chaos, controversy and, sadly, death still hovers around The Angels. At the time of the Opera House show, The Angels were arguably the biggest rock band in Australia, more popular even than AC/DC. Their influence spread as far as the scenes that would later emerge from the Sunset Strip and Seattle.

The past 15 years, however, have seen infighting, lawsuits and ill health as factions have fought for ownership of the band and its music. Even now, with the founding members in their sixties, and Doc Neeson so ill that he was only able to contribute to this story by sporadic email, old grudges die hard.

John Brewster calls himself “the black sheep” of the family. While his grandfather founded the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, his dad conducted it and his younger brother, Rick, won an under-21 piano eisteddfod at the age of 16, John was seduced by rock’n’roll. It was he who lured Rick away from Adelaide’s prestigious concert halls by convincing him to join the Moonshine Jug & String Band in 1970. An acoustic group using instruments such as washboard, harmonica and banjo, the line-up featured Bernard ‘Doc’ Neeson, an Irish immigrant and former soldier who was taking the same English And Drama course as John Brewster.

By 1974 the elder Brewster realised that if they were to make a career of it, they’d need to electrify their instruments and change their name. Dubbing themselves the Keystone Angels, and featuring the Brewster brothers on guitar (with John on vocals), Neeson on bass and drummer Charlie King, they hit the road. Support slots followed with such international stars as Tina Turner, Little Richard and Chuck Berry. But it was the three South Australian dates they played with AC/DC in early 1975 that shaped their fate.

Malcolm and Angus Young were sufficiently impressed with the Keystone Angels to recommend them to their elder brother, George, and his production partner Harry Vanda. The next time the Brewsters and Neeson rolled through Sydney, there were some special guests in the audience.

“We were playing [notorious Sydney sweatbox] Chequers, and down the stairs came Angus, Malcolm, Bon Scott, Harry Vanda and George Young,” recalls John. “I get goosebumps telling you that. George said: ‘Come to the studio tomorrow and sing a few of your songs.’”

George Young would have an immediate impact on the band. He suggested they trim down their name to The Angels. When Graham ‘Buzz’ Bidstrup replaced King on drums in 1976 and protested soon after that Neeson wasn’t up to the task on bass, it was Young who suggested Neeson switch to frontman, making way for Chris Bailey to join on bass. (Bailey had previously played with Bon Scott in the Mount Lofty Rangers.) And it was George who suggested they cut their hair, an anomaly in an age where contemporaries prided themselves on the length of their locks.

“He said: ‘You’ll be the first band in Australia to do it,’” recalls John. “And we thought, ‘That’s a really good idea.’ So we cut our hair.”

A deal with AC/DC’s production company Alberts was struck, but The Angels’ directionless 1977 self-titled debut did little to bother the charts. The financial pressures were such that they came perilously close to quitting, but they decided to honour the seven weeks of shows already booked.

“Without exaggeration, it was in that seventh week that the band started to take off,” recalls John. “All of a sudden there was a crowd.”

The surge in interest was helped by the fact that with new songs such as I Ain’t The One and Take A Long Line, The Angels had found their sound: punkish, streetwise rock’n’roll, with a lyrical focus that was far more sophisticated than their contemporaries – Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen once called the band, “AC/DC with strange lyrics.”

Also evolving was the group’s image, with Neeson using his dramatic background to craft a stage character who dressed like a dishevelled aristocrat and performed like a wild-eyed madman, spewing nonsensical philosophy in-between songs, and manipulating the band’s lighting to replicate the stark shadows of the films he loved.

“I think I may have been the first performer in Australia to use German Expressionism in a rock context,” he told Classic Rock in May 2014. Rick Brewster, meanwhile, hit upon the idea of playing this frantic music while standing absolutely motionless, eyes hidden behind dark sunglasses. Punters would constantly dare him to break character. Today the younger Brewster laughs at the memory.

“They’d rip their tops off,” he says, from his home in Tasmania. “People would suck lemons or eat onions in front of me to try to get me to laugh.”

The Angels’ gigs were rowdy affairs. Their 1976 song Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again developed its own audience chant, the fans responding to the titular question by shouting: “No way, get fucked, fuck off!”

“That’s when we really felt like the songs were connecting with the public,” Neeson said. By the time the band were special guests on David Bowie’s 1978 Australian tour, The Angels’ second album, Face To Face, had gone double platinum. By the end of the run it was triple.

With AC/DC spending most of their time overseas, by the time of 1979’s No Exit The Angels were the kings of the Australian music scene. Following the release of 1980’s Dark Room, they undertook their first US campaign – under the name Angel City, to avoid any legal issues with the pomp-rock band Angel.

Their popularity was peculiarly local, not least in the Pacific Northwest. “We were a big deal in Seattle,” says John Brewster. “Mike McCready of Pearl Jam was wearing a Face To Face shirt on tour in Australia recently. I’m told Kurt Cobain was a fan too.”

Further down the coast, future members of Guns N’ Roses and Great White had fallen in love with Face To Face (the latter band would later cover The Angels’ songs Face The Day and Can’t Shake It).

Rather than following AC/DC’s lead and relocating overseas, The Angels elected to remain in Australia. With hindsight, John Brewster admits it was a decision that hindered their Stateside career.

“If we’d stayed in America on the first album, we’d have cracked it,” he muses. “The record company were begging us to stay, but management said: ‘No, we’ve got to go back to Australia.’”

Despite their success, discontent was brewing. Prior to recording Dark Room, the band parted ways with Alberts, a move John calls “the most stupid decision ever made by management”. In 1981 Bidstrup was replaced by Brent Eccles; in 1982 Bailey was replaced by Jim Hilbun. In 1983 Neeson signalled his desire to leave the band and start a solo career. An Angels show at that year’s Narara Festival was scheduled to be his last with them. When the band blew on-the-rise headliners INXS and an already huge Men At Work off the stage, Neeson had a change of heart.

Two years later it was John Brewster who was looking for a way out. Unhappy with their 1984 album Two Minute Warning, he practically engineered his own firing.

“The final straw for the band came when they did a film clip and I was on the golf course,” says John. “They were pretty pissed off. I turned into the bad guy, so they kicked me out. I said: ‘Yeah, great.’”

The next few years were fruitful for both parties. John Brewster formed the Party Boys with ex-Status Quo bassist Alan Lancaster, and notched up an Australian No.1 with their version of John Kongos’s He’s Gonna Step On You Again. His former bandmates enjoyed a commercial purple patch with 1986’s Howling and 1990’s Beyond Salvation (the latter recorded during a brief and tempestuous union with Guns N’ Roses manager Alan Niven).

By 1993 The Angels welcomed John Brewster back into the fold. Although in the remainder of the decade they produced just one album of original material (1998’s Skin & Bone), the band remained a huge live draw. All that changed in December 1999, when Neeson was involved in a serious accident when his car was rear-ended by a truck.

What happened next is the root of the disharmony that has plagued The Angels ever since. Talking to The Age newspaper in 2007, Neeson said the accident was so severe his specialist told him he had two options: retirement, or be confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. He also talked of being virtually confined to bed for three years, which led to depression so severe he considered suicide.

The Brewsters have a different take. Though John offers only a terse “no comment”, Rick is a little more effusive: “Doc used the accident as a reason to quit the band. John and I saw the car after the accident. I think Doc actually came to rehearsal in the car – the one that was supposedly concertinaed – the next day or the one after, as if nothing had happened. It was a huge blow when we heard Doc wasn’t going to tour and he’d quit the band. John and I looked at each other in disbelief: ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’ It was a bump!”

“How odd,” Neeson told Classic Rock via email, when informed of the Brewsters’ responses. “I have no recollection of [them] seeing the car after my accident at all. My car was torn off its axle and towed away very quickly, so… I’m not sure how [they] could have seen it.”

Throughout the 90s The Angels were managed by drummer Brent Eccles, giving him a unique vantage point of the dynamics within the band. According to Eccles, the fallout from the accident was symptomatic of a bigger issue.

“Really, the relationship between the Brewsters and Doc had come to an end,” he comments. “If they had wanted it to happen, they would have remained working together. You can blame who you want, it doesn’t really matter. They couldn’t do it.”

In the years following the accident, things only got messier. In 2001, the Brewsters reclaimed ownership of The Angels’ catalogue by reuniting with Buzz Bidstrup and Chris Bailey under the monicker the Original Angels. Two years later, Neeson founded Doc Neeson’s Angels, meaning there were two groups touring Australia playing the band’s songs. When the Original Angels started calling themselves The Angels in 2006, a hefty legal document landed on the Brewsters’ doorstep.

“Doc got an injunction to stop us using the name,” says Rick, still palpably angry. “How dare he assume that he has a right to stop us using a name which is ours as much as it is his, when he voluntarily quit?”

Neeson counters: “My issue was that I was unable to work, but the band kept going out as The Angels without me as the lead singer, and I was often seeing or hearing ads using my photograph and my voice to advertise their gigs. I saw this as being deceptive and misleading.”

The ensuing mediation had an unexpected upside. In 2008 The Angels reunited with Neeson and resumed touring – albeit on the back of a mutual agreement: The Angels Reunification Deed. This states that the line-up of Neeson, Buzz Bidstrup, Chris Bailey and the Brewsters is the only one entitled to call themselves The Angels.

Inevitably that reunion also fell apart with the departure of Neeson and Bidstrup in 2010 – another matter of conjecture. The pair claim they were fired. John Brewster, who has continued to tour and record under The Angels’ name despite the agreement, insists not.

“Buzz is saying we kicked them out of the band,” says Brewster. “It’s absolute rubbish. I’ve got it in black and white. Doc left the band. Got it in black and white from Buzz: he wasn’t going to be in the band if Doc wasn’t there.”

If there’s one thing that has the potential to calm feuds, it’s ill health. In 2008 John underwent quintuple bypass surgery, from which he made a full recovery. Former bassist Chris Bailey wasn’t as fortunate. He passed away from throat cancer in April 2013. At the end of 2012 Neeson was diagnosed with a brain tumour. He was initially given 18 months to live, before going into remission. Sadly the tumour returned.

“We reached out, I don’t know how many times, as soon as we heard Doc had a brain tumour,” says Rick Brewster. “As far as we were concerned, all the hatchets were dead and buried. All we wanted to do was get together, reminisce about the Moonshine days and see him off with some peace, put all the shit behind us. But it was not to be.”

Speaking in May, Neeson had a different point of view. The singer claimed he was willing to try to mend fences, “but they weren’t… Buzz and I visited Chris the day before he died and, happily, by then the three of us had put our differences aside. I sent John messages of concern and asked after him when he had to undergo heart surgery. Just as he and Rick have enquired after me and even tried to visit me recently. But, unfortunately, unless the brothers are willing to honour the agreement, I don’t want – if you’ll pardon the pun – to see their faces again.”

On June 4, 2014, less than a month after speaking to Classic Rock for this piece, Doc Neeson passed away at the age of 67. The Brewster Brothers released a statement praising their former bandmate as “one of a kind, a totally unique performer… beneath the public persona was a gentle soul”.

Sadly for everyone involved with this groundbreaking band and the people who followed them, Neeson’s death left far too many hatchets unburied.

“I’m dreadfully sad about it,” says John Brewster. “I’ve found myself thinking about the early days, about the relationships that existed between me, Rick and Doc, and it was great. But, sadly, relationships do break down.”

For Neeson, speaking just before his death, the bad blood hadn’t quite overshadowed the band’s achievements. “After all they put me through,” he said, “all that remains is the great work we did together."

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 201, published in August 2014. The 2024 lineup of The Angels includes Rick Brewster, John Brewster, and his two sons, Sam and Tom. They're currently on tour in Australia.