This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting.

When Wanda Vincent looks out the windows of her day care center in Arlington, Texas, past the playground, she sees a row of enormous beige storage tanks. They’re connected to two wells that produce natural gas for Total, one the world’s largest fossil fuel companies. No government agency—city, state or federal—monitors the air here or inspects regularly for emissions. So Vincent has no way of knowing whether dangerous gases are leaking out of all that equipment, potentially harming the children and staff who spend their days so close to those wells.

She feels surrounded. Within two miles of her day care, 35 wells produce gas at six different sites, most of them operated by TEP Barnett USA, a subsidiary of the French energy giant Total, the dominant gas producer in Arlington. The diverse Dallas suburb of 400,000 has the fortune and misfortune of sitting atop one of the country’s largest onshore natural gas fields, the Barnett Shale.

“No one is held accountable to determine whether it’s safe or not, and yet they allow them to be there,” Vincent said. “There’s not any documentation showing we’ve done testing and you’re safe.”

Last year, as the Black and Latinx neighborhood around her day care was grappling with high COVID-19 numbers, Vincent learned from a local activist that Total wanted to drill three more wells behind her playground. Neither the company nor the city had informed her, and she took that personally. “I’m African American, and it makes me feel like they don’t value our lives.”

Twenty years of fracking in the United States has delivered not only energy independence, but also an expanding export industry in oil, natural gas and liquified natural gas. America’s drilling boom, led by Texas, has also brought heavy industry into many rural and urban communities. Millions of people now live in the shadow of oil and gas wells, unwitting participants in a massive experiment with their health. That drilling poses substantial risks to the climate as well, because methane, the main component of natural gas, is a potent greenhouse gas.

It’s hard to find a place in America where as many people live close to dense drilling as here in Tarrant County. Arlington itself is home to 52 gas well sites and hundreds of wellheads. These wells are often near residential neighborhoods, commercial strips and doctor’s offices. More than 30,000 Arlington children go to public school within half a mile of wells, according to an analysis by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, and up to 7,600 infants and young children attend private day cares within that radius. Eighty-five percent of the public school students are children of color, and more than two-thirds live in poverty. Altogether, more than half of Arlington’s public schools and day care facilities are within a half-mile of active gas production. Eight day care centers are within 600 feet, the standard setback in Arlington.

In recent years, scores of scientific studies have linked proximity to drilling to increased health risks, including childhood asthma, childhood leukemia and birth defects. The exposures can come from the fumes of diesel trucks, generators or drilling rigs. They can also come from chemicals used in fracking, as companies extract oil and gas from the shale by injecting mixtures of water, sand and chemicals. The exposures can continue over the estimated 25-year lifespan of the wells, as gases leak from wells, tanks, pipes and valves.

Researchers at Oregon State University found a 59% increase in the odds of at least one asthma hospitalization among children who lived in Texas ZIP codes with fracking. Researchers from the University of Colorado observed that children with congenital heart defects are more likely to be born to mothers living near wells, and children with leukemia are about four times more likely to be living in areas with high levels of oil and gas development. Children and developing fetuses are especially vulnerable to the toxic air pollution, fine particles and other emissions from oil and gas extraction, according to public health experts. Tarrant County has suffered high rates of childhood asthma, birth defects and other potential effects of drilling, but no government agency has ordered the kind of thorough public health assessment that could connect the dots.

The state of Colorado commissioned scientific studies, then last year overhauled its oil and gas oversight to prioritize public health. Now, most wells there cannot be closer than 2,000 feet from buildings. And the state is required to “ensure environmental justice for disproportionately impacted communities” by giving them a say in the permitting process.

Texas went the opposite direction. After the city of Denton tried to outlaw fracking within its boundaries in 2014, the state Legislature overwhelmingly adopted a law that prohibits local governments from banning drilling or passing any restriction that isn’t “commercially reasonable.” Since then, Texas localities that want to say no to gas companies have faced the prospect of expensive court battles.

Still, over the last year, Arlington has started to push back.

A City Council showdown

Last June, when the Arlington City Council convened to discuss Total’s bid to drill and frack three additional wells behind Vincent’s day care, Mother’s Heart, the nation was deep into a reckoning over racism. In the days leading up to the June 9 meeting, Arlington residents had been taking to the streets in Black Lives Matter protests. Earlier that day, the council had passed two resolutions committing to racial equity.

Mayor Jeff Williams opened the evening meeting with a moment of silence for George Floyd and a prayer: “Help us to answer the call to help each of our citizens. And especially now, our Black brothers and sisters. Here in our community and throughout our country, Lord, they are hurting as we are hurting,” Williams said, head bowed. “Help to guide us in the direction that we need to go to ensure that each of our citizens is not only treated equally, but treated well.”

Vincent was among the first to speak against the permit.

“Our clients are about 80% African American and about 20% Latino,” she said. “Can you guarantee me 100% that you’re not putting any of us in harm’s way now or in the future?”

Council Member Marvin Sutton pressed Total on whether the company would monitor the air near Mother’s Heart to see whether young children were being exposed to toxic fumes.

“No, we don’t do the air monitoring,” said Kevin Strawser, Total’s senior manager for government relations and public affairs. “We rely on the TCEQ for that.” (The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, spokesperson Gary Rasp told Reveal, does not monitor air emissions at individual drilling sites.)

Strawser said Total controls air pollution in many ways – by drilling with electric instead of diesel rigs and checking monthly for leaks. “There’s no one better in the business,” he said. “I appreciate the residents around the site and particularly the school that’s just to the north of us. And I feel like we’ve cohabitated there for the last 10 years without any issues.”

Ranjana Bhandari, executive director of Liveable Arlington, a volunteer organization that opposes urban drilling, explained how she went door to door before the pandemic, alerting Vincent and others about Total’s plan to drill more wells. “We discovered that nobody was aware of this,” she said. “We did the job that Total should have done.”

But Council Member Helen Moise, a longtime supporter of the oil and gas industry, warned that Arlington’s hands were tied. “As a council, we are aware that fracking is not a desirable activity any longer in a city,” she said. But Arlington was happy to take millions of dollars from gas companies in the past and is now “living with the consequences.”

Fracking began here on the Barnett Shale. And communities on the shale did enjoy an influx of cash in the early years of the fracking boom some 15 years ago. In Arlington, oil royalties funded a $100 million Tomorrow Foundation, which awards several million dollars a year to programs that do such things as provide medical care to infants or install energy-saving streetlights.

But the economic windfall forecast in industry-funded reports never materialized. Most of the royalties and profits went to companies or absentee owners of mineral rights. “And the potential costs, those mostly stay with and in the local community,” according to Matthew Fry, an associate professor of geography and environment at the University of North Texas, who has researched the impact of drilling in the Barnett Shale.

The industry does provide thousands of local jobs, but they now make up less than 1% of employment in the county – and today, gas production generates less than 1% of county tax revenue, according to industry and government data, a third of its peak.

Perhaps the political calculus was beginning to shift. That night, the council did something it had rarely done before. It voted 6 to 3 to reject Total’s plans to drill behind Mother’s Heart.

Wellheads spread ‘like toxic spores’

Decades ago, updates to the federal Clean Air Act required companies to install modern pollution control devices whenever they build or modify large facilities such as refineries, incinerators and power plants. It slashed pollution from power plants and other big polluters, as well as cars and trucks, vastly improving air quality in many metropolitan areas. But the law has a blind spot when it comes to oil and gas sites. It considers each well site as a separate source of pollution, even in cases like Arlington, where one company, Total, operates 33, each with multiple wells.

“This surgical loophole that no other industry in America has enjoyed prevents sprawling well sites from being considered together,” said John Walke, a former official with the Environmental Protection Agency who is now a lawyer at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It has incentivized the spreading of wellheads like toxic spores across many communities.”

The Obama administration was the first to regulate air pollution released by drilling and fracking; the EPA under his leadership regulated volatile organic compounds in 2012 and methane, a potent greenhouse gas, in 2016. After drilling, companies were required to capture the gas immediately or burn it in a flare rather than release it into the air. Companies were also required to hunt for leaks twice a year and fix them. But the Obama rules regulated only new wells, grandfathering in hundreds of thousands of others, including most of the wells in the Barnett Shale. And those regulations had barely gone into effect when they were gutted by the next president, Donald Trump.

These regulatory gaps have left much of the oversight of drilling and fracking in states’ hands. Some states, such as New York, Vermont and Maryland, have banned it. Colorado and Wyoming imposed strict rules. Others, like Texas, have given substantial leeway to industry.

“Texas does the minimum of what it has to do to meet federal standards,” said Cyrus Reed, interim director of the Sierra Club’s Texas chapter. “We’ve always argued they should be much more stringent where you have oil and gas mixing with people in close proximity.”

Two agencies in Texas regulate oil and gas production: the Texas Railroad Commission, which permits oil and gas drilling and inspects for groundwater contamination every five years, and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, which regulates air pollution. It’s responsible for ensuring that the state meets federal air pollution standards for smog, ozone and soot but leaves routine inspection of wells to gas companies like Total. The agency, which conducts inspections only in response to complaints or red flags in gas companies’ self-reports, monitors a tiny fraction of Tarrant County’s 4,001 wells. The TCEQ conducted 93 inspections here in fiscal year 2019 and 134 in fiscal year 2020, according to Gary Rasp, the TCEQ spokesperson.

The TCEQ can set individualized emission limits as part of the permitting process. But the agency offers leniency to many companies, allowing most well sites in Tarrant County, including some of Total’s, to obtain a permit by rule. That status allows companies to avoid not only individualized emission limits, but also public hearings.

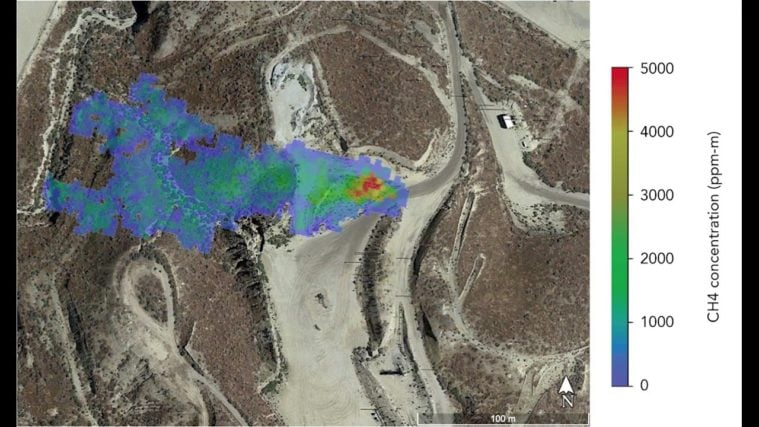

Some communities on the Barnett Shale have stepped in to fill the regulatory gaps. Kenneth Tramm’s company, Modern Geosciences, has been contracted by five municipalities to inspect well sites for leaks. In one case in Grand Prairie, a gas company reported no leaks at its well site over the course of five years. Yet in a 2015 audit, Tramm’s company found 22 leaks in 15 minutes. “A lot of people are using instruments that honestly couldn’t see numbers that would matter,” Tramm said. “Yet they derive a comfort from the performance of an inspection.”

The inadequate inspections come at a cost. He recalls visiting a site in Denton in 2018 where he said his instruments detected “a catastrophic failure.” “Something on one of their tanks is actually blowing out,” he said. “So it’s immediate lockdown.”

In Arlington, lax regulations mean no government entity has ever conducted an environmental impact or health assessment of either individual wells or the cumulative effects of the oil and gas enterprise that sprawls across the city. Nor, as Ranjana Bhandari, the anti-drilling activist, points out, has there ever been an effort to evaluate whether the drilling disproportionately affects communities of color. “I’m quite certain that there is no requirement” to assess wells’ environmental impact, Richard Gertson, the city’s assistant director of planning, told Reveal. “We’re not ignorant of the fact that any operation, much less gas drilling, is going to have impacts. We just have to balance it appropriately against our obligation not only to the citizens, but also to operators for commercially reasonable extraction.”

Researchers from the University of Texas at Austin recently studied emissions from the Barnett Shale and found that the amount of methane pollution being released per unit of gas is growing even as production declines. Some emissions come from large equipment failures, according to David Allen, a co-author of the study and a former chair of the EPA’s science advisory board, but much comes from thousands of smaller leaks across the nation’s fourth-largest metro area. Equipment parts, he said, are “going to continue to break and then get repaired and break and get repaired.”

‘We were on our own’

Bhandari, an economist and former college instructor, had her first brush with gas drilling in 2007. That’s when Chesapeake Energy Corp. sent landmen door to door in her affluent neighborhood in West Arlington, a hilly area of elegant homes on large, elaborately landscaped lots. Chesapeake, later acquired by Total, wanted the mineral rights to the gas below their homes. Bhandari, who didn’t want drilling anywhere near her son, then 5, refused to sign. Some neighbors had a different strategy, she said – they wanted the royalties without the drill rigs. Ultimately, the company agreed to move the well site about a mile away and drill horizontally from there.

The experience taught Bhandari that property owners can influence where drilling happens – in a way that renters can’t. “When I drive out of my neighborhood, within about three minutes, I see three drill sites, and they are right next door to much poorer homes,” she said.

In the years that followed, the Sierra Club, the environmental advocacy group, promoted natural gas as a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and fight climate change. So did then-President Barack Obama. Their argument at the time was that power plants using natural gas pump out far less carbon dioxide than coal-fired plants. But they didn’t factor in the vast amounts of methane – an even more potent greenhouse gas – that leak from wells and other equipment.

In the midst of the ensuing fracking boom, new drill sites kept getting approved in Arlington. Bhandari expected national environmental groups to swoop in and raise a ruckus. But “nobody came, nobody did anything,” Bhandari recalls. “We were on our own.”

The few neighborhoods that managed to keep out drilling, Bhandari noticed, were affluent like hers.

One of those rare places was an upscale, predominantly White neighborhood called Rush Creek. During a packed 2012 City Council meeting, scores of people spoke against drilling there, including then-Mayor Robert Cluck. He urged the gas company to drill horizontally from somewhere else to access the gas.

“I think there are other ways to get to this area rather than putting it in a place that’s surrounded by homes and is a beautiful place,” Cluck said. “This is a premium housing area. Why in the world would you not come from some other place?”

After the council voted to spare Rush Creek, it approved drilling in a predominantly Latinx area near Cowboys Stadium, where the median household income is $23,000, less than half the city median.

“That night was pretty revealing,” recalled Bhandari, who watched the meeting remotely. “I was pretty horrified.”

From Bhandari’s perspective, there was now so much drilling in Arlington that it had changed the character of her city. She said she’d get headaches from the fumes as she drove around town. In 2013, the City Council was considering a request to drill near two day cares. For the first time, she got up to speak. Despite voices of opposition, the council voted to approve a new drill zone at a well pad called Rocking Horse. Although Bhandari didn’t realize it at the time, that decision – to permit not a single drill site, but an entire zone – would frustrate drilling opponents years into the future.

The following year, Bhandari and a half-dozen other mothers and grandmothers banded together to launch Liveable Arlington. “Something just snapped, and I said we were going to form a group,” she recalled. “I didn’t want to be an activist. I still don’t think of myself as one. When you live in places like this, you have to do this for your children.”

Later that year, the people of nearby Denton passed their fateful ballot initiative to ban fracking, spurring the state Legislature to rise to the defense of the gas industry. House Bill 40 – one of a wave of state preemption laws sweeping the country – passed the Texas House overwhelmingly, 125-20. Rep. Chris Turner, a Democrat who represents Arlington, was one of the few to oppose it. In March, he introduced legislation to give local communities more say. But with Republicans in control of the Legislature, his bill hasn’t gotten a floor vote.

That’s left opposition in the hands of volunteers like Bhandari.

Liveable Arlington’s first big win was in 2017, when a gas company applied to drill a wastewater injection well near Lake Arlington, the source of drinking water for half a million people. Bhandari’s group organized a petition opposing the permit, and the company withdrew its application.

Before Mother’s Heart, the only time the Arlington City Council had rejected Total’s drilling plans was in 2018, when the company sought a permit near another day care, Cornerstone Academy. But after Total promised to relocate Cornerstone’s playground, the council reversed itself and approved the wells.

Given that experience, Bhandari said she was on edge last summer, “waiting to find out what mischief they’re planning. I’ll be damned if I’m going to let Total win something here easily.”

Weak rules and no will to enforce

At first blush, the Mother’s Heart vote seemed like a turning point. But in the ensuing months, Total continued to press for the right to drill next to preschools. And previous City Council votes, combined with that 2015 state law, would make it hard for the city to say no.

Total did not immediately challenge the Mother’s Heart vote. It simply pivoted to securing a permit to drill seven new wells at Rocking Horse, the well pad that inspired Bhandari’s first anti-fracking speech. Rocking Horse is in Council Member Marvin Sutton’s district, where the majority of residents are African American or Latinx. It’s also right next to two day cares licensed to care for about 250 kids.

Directly to the east of the well pad lies block after block of modest, single-family homes built in the 1980s. The day cares are just to the northeast. But Total didn’t have to face those parents or residents in a public hearing. Nor did Sutton and his council colleagues get to vote. In that 2013 vote – the one where Bhandari first spoke out and long before Sutton was elected – the City Council had granted Total a “drill zone” at Rocking Horse, giving the company the indefinite right to secure new drilling permits without a vote or public meeting.

Gas companies had pressed for the city to create these zones. “There is no need to burden council with additional permit approvals,” one gas company, Vantage, argued at the time.

“It’s completely emblematic of all the things that are wrong with urban drilling in Arlington,” Bhandari said. “You see it happening recklessly close to homes, schools and medical offices. You see no neighborhood input. You see really, really weak rules and no will or desire on the part of local government or the state to see that those rules are actually implemented.”

Reveal asked Richard Gertson, the Arlington planning official, about his office’s decision to approve the permits at Rocking Horse right after the council blocked drilling near Mother’s Heart.

“I understand those who may say, ‘Well, they’re exactly the same aren’t they?’ It’s drilling and you’ve got day cares and all these other uses, but it’s a different situation as far as we’re concerned,” he said. “Once the council establishes that drill zone, as they did in 2013, then any future permit applications, if they are inside that drill zone, they may be approved administratively.”

In November, 10 days after Total had begun drilling under its new permits at Rocking Horse, Liveable Arlington captured video of black smoke billowing from the machinery. Bhandari suspected the company may have been using a diesel rig.

Bhandari sent the video to a city inspector, who confirmed her suspicions. The city let Total finish the well that was underway but required the company to halt additional work until it brought in an electric rig, Gertson said.

“Those little children have no voice in this,” Bhandari said. “They are completely at the mercy of this nexus of politicians and an industry that just operates like it’s above the law.” She said Total’s use of the diesel rig exemplifies the company’s complete disregard for the rules – until it gets caught.

In Texas, there is rarely anyone looking. Last year, when Total asked the state environmental agency for a permit by rule to drill and frack those seven new wells at Rocking Horse, the agency laid out its lack of oversight in a letter: “Be advised no review has been done by TCEQ to verify that the site meets the requirements of the permit by rule.”

Gertson, too, was explicit that his office expects gas operators to police themselves. “That’s not our procedure to try to babysit a site or to monitor a site during drilling,” he said.

Total declined to respond to questions, but Kevin Strawser, the senior manager, issued a brief statement. “We operate our sites in a safe and environmentally responsible way that is compliant with the requirements of our business,” he said, adding that the company works “diligently to ensure the safety and quality of life for our neighbors near our sites.”

‘We’ve opened the door’

Marvin Sutton spent his career as an air traffic controller at the Dallas Fort Worth International Airport, where keeping people safe was his mission. After the diesel rig incident, he headed over to the Rocking Horse well site to assess the risks. The Childcare Network is just 359 feet away from the drilling, and its outdoor play area is even closer.

“We know that distance between airplanes increases our margin of safety,” Sutton said. “The goal is to add a margin of safety and protect the kids.”

His decision to run for City Council was driven by a desire to improve public safety in his hometown. He ran six times before winning a seat in 2019.

Air pollution worries him, but so does the risk of accidents, like when a gas pipeline released 60,000 pounds of volatile organic compounds near Arlington during February’s cold snap or a 2015 well blowout sent 42,800 gallons of fracking fluid onto Arlington streets.

Exasperated that a City Council decision eight years ago prevented him from protecting the day cares near Rocking Horse today, Sutton proposed to change the rules. He sought to measure the 600-foot setback between wells and day cares not from the facility, but from the property line. That was enough to run afoul of Total.

In February email exchanges obtained by Reveal, Total told city staff that it wanted the city to exclude its existing well sites from the proposed restrictions, mentioning one well pad in particular, called Galletta. Failing to do so, wrote Julie Jones, Total’s manager for regulation and real estate, “could prohibit further development of wells at that location.” Total went on to claim that failing to issue the exemption would violate state law – and cited HB 40 by name. Galletta is 280 feet from a shopping center that’s home to Little Texans of Arlington Daycare.

At a City Council meeting in February, city staff presented satellite images showing two Total well sites, including Galletta, operating outside of drill zones and adjacent to day cares. The well sites are so close to day cares, they said, that changing the setback from buildings to property lines could indeed prevent Total from drilling new wells there. The staff report indicated meetings with the gas industry, but not with the day cares. And it noted that the gas industry saw the measure as a slippery slope; next, the city would want to increase setbacks for other protected uses, such as schools or doctor’s offices.

Council Member Andrew Piel, an industry supporter, cited Total’s email saying, “I didn’t want to expose the city to litigation.”

The email exchanges show an extensive back and forth between Arlington’s staff and Total’s. “I know staff is and will continue to look for possible solutions to avoid a potential legal conflict,” wrote Galen Gatten, the city’s land use attorney.

The council compromised, deciding that the 600-foot setback will now also apply to playgrounds, but not property lines. The ordinance change, adopted unanimously in April, also grandfathered in existing drill zones, which would allow more drilling at Rocking Horse.

Sutton saw the ordinance change as “testing the waters,” a step toward reasserting local control. So was his recent mayoral bid, in which he came in third in a crowded field, running on a platform that emphasized drilling safety. “We’ve opened the door,” he said, “and we’re going to continue to open that door, to get what we really need to protect our citizens and to protect our kids.”

Even as the nation grapples with climate change and recognizes the need to wean itself off fossil fuels, the residents of Arlington – and millions of others who live close to wells – can expect to keep living with drilling for decades. Their fate now turns on the demands of a growing new export industry that’s ramping up to ship methane across the globe in the form of liquified natural gas.

President Joe Biden has declared his commitment to slashing greenhouse gas pollution by at least 50% by the end of the decade. But he has also said he will not ban fracking – and he has yet to lay out how he will square those two commitments. As for liquefied natural gas, Biden’s energy secretary, Jennifer Granholm, told Congress in January that these exports “have an important role to play in reducing international consumption of fuels that have greater contribution to greenhouse gas emissions.”

Total is based in France, which banned fracking in 2017. Yet thanks in part to drilling in U.S. shale communities like Arlington, the company is a player in liquefied natural gas on a global scale. Total has just rebranded as TotalEnergies, building on its pledge to be a net-zero greenhouse gas polluter by 2050. But its plan to be “a world-class player in the energy transition” still depends heavily on drilling and fracking. “Total has made natural gas, the least polluting of all fossil fuels, a cornerstone of its strategy in order to meet the growing global demand for energy while helping to mitigate climate change,” the company said in an April report.

The EPA, stuck figuring out how to manage fracking’s environmental fallout, begins listening sessions today as it prepares to draft new rules to control the inevitable methane leaks. Many people who are trying to carve out lives inside the drill zone – from Texas to California, Oklahoma, Ohio, Pennsylvania and beyond – have signed up to speak, as has Bhandari. She wants answers about why the U.S. government lets Total drill in the backyard of American day cares when it cannot frack anywhere in its home country.

“We have this ingrained sense that this couldn’t happen in America, so we are willfully looking at it and choosing not to recognize it for what it is,” Bhandari said. “This is ecocide.”

Reveal data reporter Mohamed Al Elew contributed to this story. It was edited by Esther Kaplan, Soo Oh and Taki Telonidis. It was copy edited by Nikki Frick.

This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting. Get the next big story emailed directly to you. Sign up at revealnews.org/newsletter.