Not since 2000 under Jacques Chirac had a French president held a state visit in Germany. It was, therefore, with some anticipation that Chancellor Olaf Scholz greeted his counterpart, Emmanuel Macron, from 26 until 28 May in Berlin, Dresden and Münster, days away from the European elections and in a year marked by many Second World World commemorations. Speaking at a press conference at the end of the stay, Macron said both governments had agreed to reinforce their partnership across a number of strategic areas, including decarbonisation and the climate transition.

If these words are to signify anything other than wishful pleasantries, however, both leaders could do worse than thinking of their energy cooperation. But can the renewables enthusiasts of Berlin and atomic supporters of Paris ever see eye to eye? Despite recent quarrels on the use for nuclear power, the role of gas in the energy transition and the future of combustion engines, our French German research at Grenoble Management School and Deutsch-Französisches Institut für Umweltforschung at [Karlsruhe Institute of Technology] show that French and German citizens share surprisingly similar views on energy.

Two seemingly irreconcilable energy profiles

On paper, everything appears to oppose these two countries’ approaches to energy.

France – it’s no secret – relies heavily on nuclear power. In 2023, the sector accounted for 72% of its electricity mix - the highest percentage for a country worldwide. While the Fukushima meltdown in March 2011 prompted neighbouring Germany to phase out nuclear, the French conservative president Nicolas Sarkozy vowed at the time not to reduce its reliance on the atom, a move which he said would have broken “the political consensus of the last 65 years at the risk of destroying jobs in French industry”. The pro-nuclear stance has continued to expand under president Emmanuel Macron. In light of ageing plants, an expected increase in electricity demand and increasingly ambitious climate goals, in February 2022 Macron revealed plans to build six new nuclear EPR power reactors by 2035, with a view to possibly adding a further 8 by 2050.

Germany, in contrast, couldn’t have more different policies. Long home to a strong anti-nuclear movement, the Fukushima disaster led even trained physicists and previous atomic energy advocate, then chancellor Angela Merkel, to question her beliefs in the possibility of safe nuclear power. Three months later, the parliament voted to phase out atomic energy by late 2022. Its climate plans commit it to generate 80% of its electricity from renewable energy sources by 2030. Critics point out that this has resulted in Germany’s dependence on coal for electricity generation (~25% in 2023), but plans phase out all coal-fired power generation by 2038.

Different policies, similar attitudes

As energy policy watchers, we expected that these two country profiles should have translated in different energy preferences between citizens. And yet, our research tells another story. Our recent survey of over 2,000 people (with 1,006 participants in France and 1,004 in Germany) shows that overall, support for renewables, fossil fuels, and nuclear power aligns with citizens’ political preferences.

Ranking of preferences for energy sources: renewable energies ahead of nuclear – coal lags behind

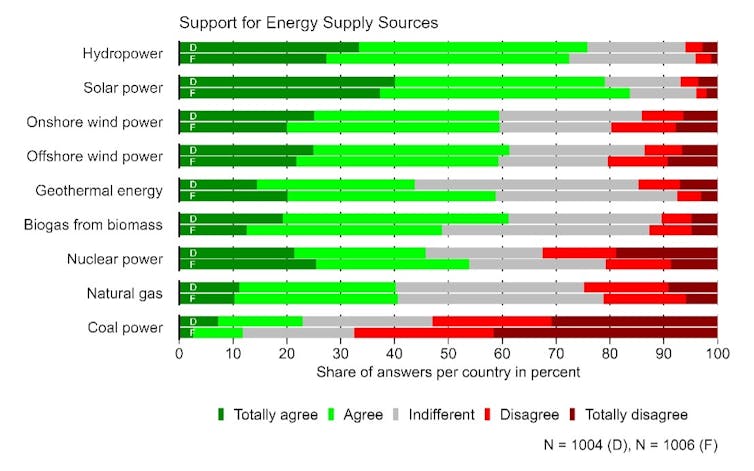

When asked about their support for different energy sources for electricity generation, respondents in France and Germany indicate strong support for renewable energy sources, in particular for solar and hydropower, but also for onshore and offshore wind energy (see Figure 1).

At the same time, the share of onshore and offshore wind energy opponents (i.e., those responding ‘totally disagree’ or ‘disagree’) is 6 percentage points higher in France than in Germany. Respondents in France tend to back geothermal energy (such as water from hot springs, for example) more often, while Germans favour biogas.

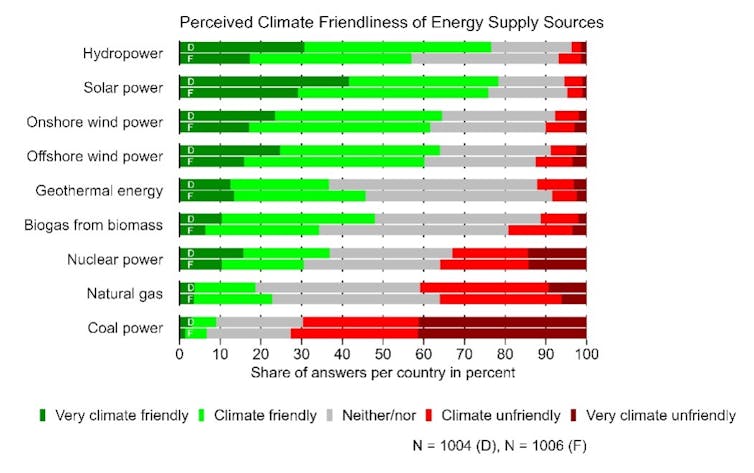

Support for nuclear power is admittedly stronger in France than in Germany, but that’s by a small margin considering that Berlin has already phased it out. Yet, results also show more opposition to nuclear power in Germany than in France (33% opposed in Germany, compared to 21% in France). Surprisingly, a larger share of respondents in Germany than in France considers nuclear power to be climate friendly (see Figure 3) and cheap (see Figure 4). Coal has more supporters in Germany than in France, but finds itself at the bottom of the popularity ladder in both countries by a significant margin.

Additional analyses reveal that in Germany, people who support nuclear energy also tend to support coal and natural gas, indicating a preference among some of the population for ‘traditional’ technologies. On the contrary, in France, there is no relationship between public support for nuclear and coal power, possibly because coal power in particular has played a minor role in the French electricity mix for the past decades.

Political leanings are key

Support for different energy sources appears remarkably similar in France and Germany. Within each country, however, preferences are strongly related to political identity. In both countries, individuals identifying with environmentally-oriented policies tend to show stronger support for renewables while opposing coal and nuclear energy. In Germany (but not in France), this group also displays a greater opposition to natural gas.

In France, the absence of a correlation between identifying with environmentally-oriented policies and opposition to natural gas is surprising, as natural gas is considered the second least climate-friendly technology by respondents (see Figure 3). One explanation may be that, in comparison to Germany, natural gas plays a significantly smaller role in the already decarbonized electricity mix in France.

In contrast, participants identifying as conservatives show less support for renewables and are not as strongly opposed to coal, natural gas, and nuclear power. Moreover, individuals identifying with nationally-oriented policies demonstrate a stronger support for nuclear energy in both countries, possibly because they perceive nuclear power as an effective means of reducing energy import dependency (Figure 5). In Germany (but not in France), this group also displays a greater backing for natural gas, biogas, and coal.

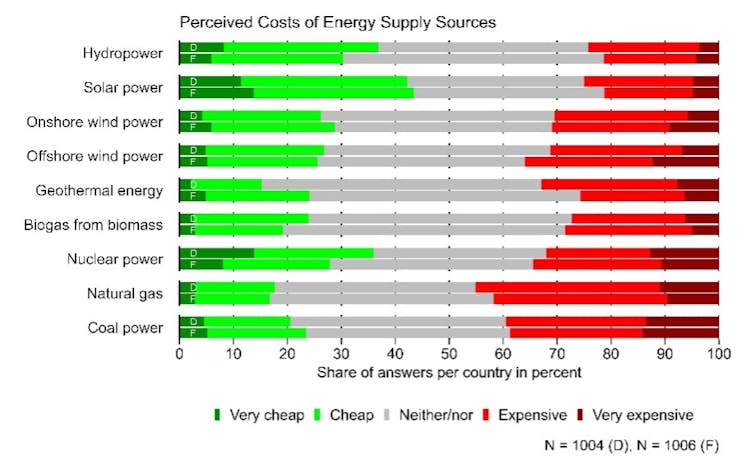

The costs of energy

In both France and Germany, the strong differences in public support for various energy sources are mirrored by differing public perceptions of their climate friendliness (see Figure 3). In contrast, perceptions of the costliness of electricity generation vary less across different energy sources (see Figure 4). Nonetheless, political identity seems to influence costs perceptions: In Germany, individuals that identify as conservatives and nationalists have a stronger tendency to view nuclear energy, coal, and gas as cheap.

In France, this tendency is only observed for nuclear energy. One explanation for this difference across countries might be that in comparison to Germany, electricity prices for households were significantly lower in France over the past decades, where it was mainly produced by nuclear power. However, those identifying with environmentally oriented policies are more inclined to perceive renewable energy sources as low-cost in both countries.

Owing to disparities in the electricity mix and taxation policies, household electricity prices are notably higher in Germany compared to France. In the latter half of 2023, households in Germany grappled with rates as high as 40 cents per kWh, marking the highest price within the EU, while their counterparts in France contended with a comparatively lower rate of 25.5 cents per kWh.

A significant majority of respondents in Germany recognize the fact that electricity comes at a lower price for end-users on the other side of the Rhine (see Figure 5). In contrast, respondents in France appear less aware of price differences across the two countries, with nearly equal proportions believing electricity to be cheaper or more expensive in France than in Germany.

Beyond French German polarisation

To overcome the political divide on energy policy, it will not be enough for French and German politicians to simply point to the climate friendliness of renewables, since most people in both countries are already aware of it. Rather, it seems necessary to show how the use of renewable energy sources can promote a positive development of consumer prices, competitiveness, and energy sovereignty in France and Germany – arguments more likely to sway conservatives.

Beyond these insights on energy sources, the survey also investigates support for the energy transition which is defined as all measures to decrease greenhouse gas emissions such as carbon dioxide caused by the production and consumption of energy.

Respondents in both countries and across the political spectrum declared supporting the energy transition in their own country (56% in favor in Germany, 61% in France) with less than 17% of respondents opposing it. Across both countries, about two thirds of respondents agreed that France and Germany should cooperate more to propel the energy transition, with less than 10% opposed to closer ties. Despite this, many are unsure of how to go about it. Let’s see if this support for greater cooperation among EU member states will be reflected in the results of the forthcoming European elections.

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.