Michelle Cahill’s Daisy & Woolf takes its epigraph and its inspiration from Virginia Woolf’s feminist essay A Room of One’s Own (1929): “A woman writing thinks back through her mothers.”

But who are those mothers? Who are those women who dared to write – and whose voices we have not heard?

Review: Daisy & Woolf – Michelle Cahill (Hachette)

Daisy & Woolf is Cahill’s first novel, although she has previously published collections of poetry and short stories, including Letter to Pessoa, which won a New South Wales Premier’s Literary Award in 2017. The novel is boldly touted as a successor to Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) in its revising of a literary classic.

Read more: Guide to the classics: A Room of One's Own, Virginia Woolf's feminist call to arms

Wide Sargasso Sea tells the story of Bertha (whom Rhys renames Antoinette), Rochester’s first wife in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Bertha is cast as a “madwoman”, a burden on her husband, who is banished to the attic. Wide Sargasso Sea gives Antoinette a voice and a life, reimagining her so powerfully that Jane Eyre can never be read the same way again.

Cahill’s novel similarly seeks to tell the story of Daisy Simmons, a marginalised character in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925). Daisy is the Anglo-Indian lover of Peter Walsh, himself the former lover of Clarissa Dalloway. She features very little in Woolf’s novel, where she is merely the object of Peter’s desire. But Mina, the narrator of Daisy & Woolf, is determined to bring Daisy out of Mrs Dalloway’s shadow:

I need to give Daisy a voice and a body. Daisy is the character whose story I hope to write, the woman whom Virginia Woolf had scarcely sketched as naïve, vulnerable and wanton, giving it away too easily, pretty and young, all dressed in white.

Although Mrs Dalloway is a novel focussed on the experience of its eponymous character and her journey around London one June day while she is preparing for a party at her home, the novel touches on the lives of others.

The most famous marginal character in Mrs Dalloway is Septimus Smith, the shell-shocked soldier, who represents the silencing of the wartime trauma of a generation of young men. Daisy represents the silencing of another kind of social and global trauma. She speaks to the impacts of gender, race and class in colonial India.

Cahill’s narrator, Mina, has taken accommodation in Tavistock Square, in the Bloomsbury district of London, close to where Woolf lived with her husband Leonard, and where they established Hogarth Press in the basement of their home. Like the fictional Daisy, and like Cahill herself, Mina is of Indian heritage; like Daisy, she experiences oppression and exploitation.

It is this kind of orientalism, an assumed exoticism born of colonialism, which Mina and Cahill seek to conquer. The novel strives to overcome and rewrite Daisy’s objectification at the hands of Peter, to be sure, but also at the hands of Woolf:

The whole book bears the scratching of Peter’s idealised passions, sublimated on to Daisy and Clarissa, and there’s Virginia having it materialise all the same, so that it is hard to know if she sympathises with his awkward ways or if she holds Peter in contempt.

Read more: Virginia Woolf: writing death and illness into the national story of post-first world war Britain

The power dynamic of privilege

It is here that Cahill comes up against Woolf.

Woolf the matriarch, the grand figure of high modernism, we might even say the snob, is set up in contradistinction to Daisy – the small, the common, the inoffensive, the feminine.

I noted in my recent overview of Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own the need for us to remember that

Woolf herself came from a privileged position, such that she could much more easily advise against “doing work that one did not wish to do, and to do it like a slave, flattering and fawning”.

“Woolf champions white women,” observes Mina;

she argues brilliantly against their subjection in A Room of One’s Own and in Three Guineas, but she uses her genius to slay Daisy Simmons.

In this way, we see how Daisy & Woolf establishes the power dynamic inherent in the construction of history and story. Who is permitted to speak? Who is silenced? Mina asks questions designed to penetrate the assumptions and silences inherent in Mrs Dalloway, wondering, for instance:

But what about Radhika, the servant girl, the nanny; have I fixed and limited her? How does she speak if she is illiterate? […] Is it ever possible to tell stories which are not in some way partial, appropriating?

Cahill’s novel thus falls into a genre Linda Hutcheon called “historiographic metafiction” – narratives which rethink how the stories of the past have been told and attend to the voices of those who have not yet been heard.

Mrs Dalloway is not the only Modernist work to which Daisy and Woolf makes reference. Mina riffs on the language of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922) (“They say April is the cruellest month, breeding lilacs”), Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1927) (“waiting for the future to show”), and the setting and behaviours of the so-called “Rhys woman” – a woman who is sexually objectified, often seen walking in the rain along the Gray’s Inn Road.

Some of these allusions are cited in a brief set of endnotes, themselves an echo of the famously impenetrable notes which accompany The Waste Land. But not all of the references are made explicit, exposing our absorption in a Western canon in which such citations are assumed to be recognisable: these are the voices which speak loudest.

To construct this historiographic metafiction, Daisy & Woolf blends the contemporary narrative of the writer, Mina, a character the reader may come perilously close to reading as Cahill herself, with the epistolary novel she is writing. The letters are primarily from Daisy and thus tell, for the first time, her story in her own words.

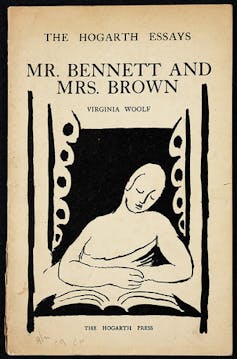

In this way, Cahill models Woolf’s observation that modernism was interested in developing characters from the inside rather than the outside. In Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown (1924), Woolf described this shift from the social realism of the 19th century to the psychological realism of the early 20th century.

That Daisy’s story is told through letters underscores the way in which ordinary women – those not afforded Woolf’s intellectual and class privileges – wrote. Letters and diaries are where those silenced voices can be heard with authenticity, without artifice.

“Though you are a master, and I have little expertise,” Daisy remarks to Peter, “perhaps we share the same compulsion to narrate.”

Despite her dedication, however, ultimately Mina concludes that character and identity must always be partial and incomplete, even for herself. She realises that even she only

exist[s] somewhere between these jottings, my Twitter account, my selfies, my social media posts and messages, revealing to my self and to others who I am.

Character thus “depend[s] entirely on narration”. Every story is inextricable from the way it is told; story and discourse are irrevocably entwined. History, whether individual or collective, can never be entire. T

he writer’s responsibility is simply to keep telling stories “[w]ith the stubbornness of a brown girl refusing to be silenced”, thereby approaching something more like truth. These are the stories of our mothers, Daisy & Woolf suggests – the stories the contemporary woman writer must “think back through”.

Jessica Gildersleeve does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.