The Go-Go’s were used to having their story written for them. It’s happened to any band that has weathered a press junket: the same handful of anecdotes, origin myths, and quotes trotted out in every interview, profile, and concert preview. Let’s get that out of the way quickly then. When the Los Angeles-based five-piece first began gigging at clubs on the Sunset Strip in the late ’70s, most of them were novices. “Every story mentioned how the Go-Go’s could barely play when they started, and look at them now,” bassist Kathy Valentine, an Austin native, would write years later. “It gave every writer a ready-made story hook, the fairytale fable.”

How many people have been to a show, shoes epoxied to the floor by layers of spilled drinks, and watched a young band fumble through a set? It’s a forgivable fault, part of figuring things out—especially in the punk scene the Go-Go’s came up in—and something that becomes a moot point with practice and time. This, perhaps, wouldn’t have been such a narrative sticking point if the press hadn’t had another prebaked novelty in their arsenal: The Go-Go’s were all women. So throughout their career, one that earned them a double-platinum record certification and a Grammy nod, the Go-Go’s in some way remained miracles. It was a version of the same trope plaguing professional women across industries and decades: Isn’t she lucky to be here?

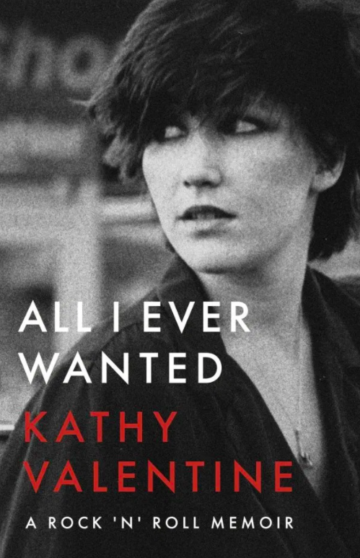

In her new memoir, All I Ever Wanted, Valentine unveils the countless other storylines that could have been told. The Go-Go’s remain the only all-female band to date to make it to the top of the Billboard charts by writing and playing their own music. Yet as revolutionaries emerged before them, no one seemed willing to dig deeper. “Reporters never asked our opinions on anything of substance,” Valentine remembers. “There were no conversations about sexism or feminism. The most common question remained ‘What’s it like to be in an all-girl band?’” With frank, jarringly unsentimental storytelling, Valentine reclaims not only the band’s narrative, but more importantly, her own.

Much of All I Ever Wanted’s breakneck pace is set by world tours and the music industry’s hustle and excess, but Valentine’s childhood trauma is similarly dizzying. Raised in Austin by her mother, a British expat “fueled by Virginia Slims and Lipton tea,” Valentine began experimenting with drugs and alcohol as a preteen. Some of the experiences that marked her adolescence felt like a byproduct of a freewheeling decade: “You haven’t lived until you’ve been on LSD when a race riot starts in your stupid school,” she writes, sounding like a 1970s Mad Lib. But others are far more sinister, personal hardships.

At 12, Valentine had an abortion. It was 1971, two years before Roe v. Wade codified women’s right to choose in Texas and across the country. Valentine’s mother whisked her away to California for the procedure, determined to make the trip a fun getaway. But Valentine’s recollections are dark. “I had lost my childhood, vacuumed out with the zygote, and with that loss, my mom and I had become like a couple of girlfriends getting out of a jam.”

Other childhood experiences Valentine recounts cut deep, including a rape that no one called a rape. Readers can feel Valentine’s loneliness and isolation, furthered by a mother who acted more as an enabling roommate than a caregiver. Still, Valentine demonstrated an early knack for self-preservation. “There’s always a crack in the wall of bad where the good can start to seep in,” she writes. “You just have to notice it and let it happen.” For her, that crack in the wall was music.

By the time she turned 18, Valentine had shared stages with Texas royalty—Jimmie Vaughan, Doug Sahm—making her name as a hard-charging frontwoman and guitarist. But “the shortage of young, female musicians in Austin was frustrating my ambitions,” she recalls. LA, she believed, was where “the real shit happened,” so she picked up and moved, playing gigs around town with her band, the Textones. Her big break with the Go-Go’s came by happenstance: She subbed in on bass—an instrument she’d never played before (cue the press!)—on a three-show stint at West Hollywood’s Whisky a Go Go. After that, she signed on to a band that would blow up less than two years later.

When the Go-Go’s stormed across America in the early ’80s promoting their debut album, Beauty and the Beat, reviews still characterized them as little more than cutesy. “Guy bands were never described as perky and chirpy or adorable and cute,” she writes. But the many pages Valentine devotes to tour antics share the raucousness of many rock god memoirs. Sex? Drugs? Rock and roll? Check, check, check. “If ‘pop sweethearts’ did acid at Graceland, threw up on the floor at fancy restaurants … and stayed up all night writing songs and playing guitars, well, maybe their stupid label might fit,” Valentine concludes.

It’s doubtful that Valentine (or any of the Go-Go’s) cared much about being recognized for their ability to party like the guys. She takes great care in chronicling it, sure—the onslaught of debauchery is partly what makes All I Ever Wanted a quick and engrossing read, and provides a detailed backdrop for analysis now that Valentine is sober. But she also seems to be righting the record. She strives to show that the Go-Go’s weren’t bubbly ingenues on MTV, but women who helped define a decade of pop and punk, laying groundwork for sounds ranging from the Bangles to Bikini Kill. And if the partying came with that rock star lifestyle, she wanted recognition for that too.

Before starting the memoir, I hoped Valentine would paint the Go-Go’s as burn-it-all-down riot grrrls intent on destroying the patriarchy. Or maybe as precursors to the glammed-up-and-owning-it feminism of the Spice Girls. But maybe, like so many music writers before me, I was guilty of trying to fit them into a mold. The Go-Go’s may have paved the way for a movement of female rock and pop, but Valentine doesn’t discuss them like some centralized plot. Their radicalism was simply that they existed.

“We were five women having a good time like a bunch of girlfriends might do, except we played guitars and drums and wrote catchy songs,” Valentine remembers. “It was revolutionary.”

Read more from the Observer:

-

Mi Barrio No Se Vende: San Antonio is planning to demolish its oldest and largest public housing project, threatening the future of a deeply historic neighborhood—one that anchors the city’s identity as the nation’s Mexican American capital.

-

From Jail to the Streets: One Texan’s Story During COVID-19: The homeless are 11 times more likely to be incarcerated than the rest of the population.

-

‘I’m in Limbo Here’: Texans Are Met with an Overwhelmed and Antiquated State Unemployment System: The safety net meant to support the second largest workforce in the country is using decades-old technology. The workforce agency was trying to replace it when the pandemic hit.