On cold nights in July, Adelaide audiences are flocking to an extraordinary festival of light and sound.

The top bill of the Illuminate festival is Wisdom of AI Light, an immersive digital performance in which the audience experience art meshed with science at breakneck speed. Billed as a “digital renaissance”, it is much more than that.

Held in a large pop-up space, the creators are the Istanbul-based Ouchhh Studio who are exploring the limits of what machines can do.

Spurred on by Alan Turing’s Computing machinery and intelligence (1950), a host of digital artists have been exploring how machines replace the artist in thinking, making art and music.

Ouchhh Studio take the digital art revolution to a whole new level. Art history is a data set from which their artificial intelligence scientists, animators and designers create algorithms that produce stunning visual effects that dance over the walls and floor of the space.

Every so often, Leonardo da Vinci’s enigmatic Mona Lisa (1503) or his Vitruvian Man (1490) appear, along with fragments from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-12) or Pieta (1498-99), only to dissolve into particles.

In the second part of the performance, the creators turn to the writings of Galileo, Einstein and other physicists. Snippets of their text and scientific symbols dance across the walls and floor, only to dissolve into computer language or abstract designs.

The partnership of the Ouchhh Studio with scientists at CERN and NASA is ground-breaking: their multi-sensory performance is a visual feast.

Read more: Friday essay: Rise of the artistic machines

Painting trees with light

In the botanical gardens, the Montreal-based Moment Factory are presenting another after-dark spectacle, Light Cycles. The Moment Factory’s laboratory is the forest. Trees, plants and built structures become their canvas.

A curated pathway through the gardens takes audience members on a journey where light, music and video interact. The world of the everyday slips away and nature comes alive.

At one point, you move through a maze of intersecting laser lights. At another, lights dance up and down giant trees accompanied by thumping music that emulate the fantasy-laden tree-monsters of children’s stories.

Further on, a choreography of lights dance across a lake performing movements to rival contemporary dance. The finale is the changing light parade at the Palm House.

This deeply performative, immersive and experiential walk through light and sound is utterly stunning.

Rewriting history

Illuminate Adelaide is also lighting up buildings throughout the city after dark. The façade of the Art Gallery of South Australia is host to Vincent Namatjira’s Going Out Bush.

The gallery’s classical columns become gum trees in the Hermannsburg style of watercolour painting made famous by Albert Namatjira, while Vincent weaves in and out of Country in his great-grandfather’s signature green truck.

The imagery is, at one level, jocular and folksy. At a deeper level it is rewriting colonial history. The scene is set in Indulkana, the artist’s home in the APY (Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara) Lands, where the local football team plays and the camp dog roams.

Colonial power, symbolised by images of Captain Cook and the Queen, becomes First Nations power. The heads of Captain Cook and the Queen are replaced by Vincent Namatjira’s: a nighttime dream or more?

Read more: Terra nullius interruptus: Captain James Cook and absent presence in First Nations art

Studies in melancholy

Within the walls of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Robert Wilson: Moving Portraits is on show. While not a part of Illuminate Adelaide, its focus is also light, sound and movement.

Wilson’s fascination is stillness – and the movement in stillness. His 23 video portraits are teasingly titled “moving portraits”.

Wilson is a major contemporary art world figure, best known for his collaboration with Philip Glass in Einstein on the Beach (1975), and most recently for his radical new interpretation of Handel’s Messiah (2020). In his highly innovative work across the performing and visual arts, the reductive forms of space and time are always at play.

Some of Wilson’s subjects for his highly staged, theatrical pieces in his Moving Portraits are actors because they are trained to hold a pose. The scenes created are frequently steeped in art history, cinema or literature as in Lady Gaga: Mademoiselle Caroline Riviere (2013).

This video portrait, which draws on Jean Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s famous 1806 portrait, replicates its costume and pose perfectly, but for Wilson it is a study in melancholy. The youthful Caroline Riviere died a year after Ingres’s portrait commission.

In filming, Lady Gaga held the pose for seven hours. The video portrait, which runs on a loop over several minutes, is intensely still and subdued. A tear intermittently runs down Lady Gaga’s face. A snow goose occasionally flies above to allude to the brevity and beauty of life.

Each Wilson video portrait is paired with objects from the gallery’s collection, for this one it is a Roman balsarium (c.50-200 CE), a delicate glass tear-collecting receptacle a mere 13cm high.

Wilson sees his portraits as opening up a psychological window for the viewer, the balsarium is uncanny in completing the effect.

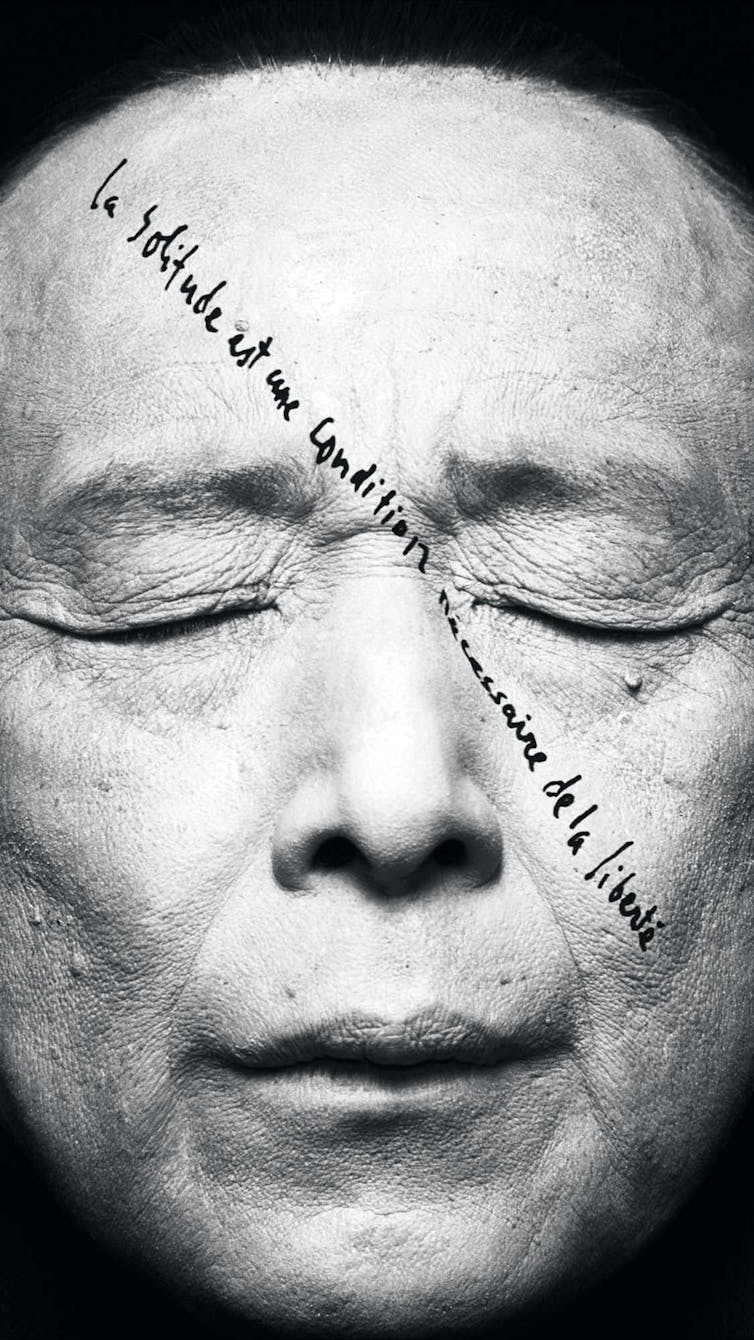

In another intense portrait of Chinese expatriate writer and Nobel Laureate for Literature, Gao Xingjian, Writer (2005), space is compressed. The portrait zones in on his cropped face. Every facial line and skin pore are visible.

With his eyes closed, apart from the slight flicker of the eyelids, the face becomes a record of struggle and success. Text in French from Jean Paul Sartre, edges slowly across his face reading, in English, “solitude is a necessary condition for liberty”.

The video portraits extend to animals, the human-animal nexus a particular fascination for Wilson. This includes the intriguing Ivory, Black Panther (2006) which Wilson and his technicians filmed for 23 long minutes in a domestic setting, the panther’s eyes directed at these intruders.

The union between the humans and this potentially dangerous animal is palpable: the stillness is both unnerving and its drawcard.

Other moving portraits include a softer, more vulnerable Brad Pitt, Actor (2004), clad only in boxer shorts and socks, standing in the rain and holding a water pistol, a reference to Alfred Hitchcock.

Wilson works collaboratively. That starts with his subject, and extends to his creative team who, following the theatrically staged shoot, spend another two weeks editing and sound mixing. Each portrait comes with an accompanying soundtrack.

When looking at the Wilson video portraits, time slows down; the slight movement in the imagery, such as Winona Ryder’s feather on her hat swaying in her intriguing Winona Ryder Actress (2004), requires careful looking. Viewers in the exhibition space are being subtly inducted into Wilson’s mantra of “movement in stillness” in this deeply affective series which is poetry in motion.

A truly exquisite exhibition.

Illuminate Adelaide is at multiple venues until July 31. Robert Wilson: Moving Portraits is at the Art Gallery of South Australia until October 3.

Catherine Speck has received funding from the ARC to research Australian art exhibitions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.