One of the many casualties of unchecked climate change is Arctic ice. Each year, the ice seasonally melts, but it has recently been receding faster in the summer than it can refreeze in winter. This rapid disappearance has accelerated sea level rise and heat waves on every continent. And the warmer the Earth gets—and stays—the worse other ice sheets and glaciers across the planet fare.

Two anthropologists from Rice University, Dominic Boyer and Cymene Howe, documented the effects on one such glacier in Iceland, Okjökull (nicknamed Ok). In 2014, Boyer and Howe stumbled on a news story that noted Ok had lost so much ice that it could no longer officially be called a glacier. The researchers decided to look into the story of how a glacier “dies,” eventually producing a documentary about the event, Not Ok, which premiered in 2018.

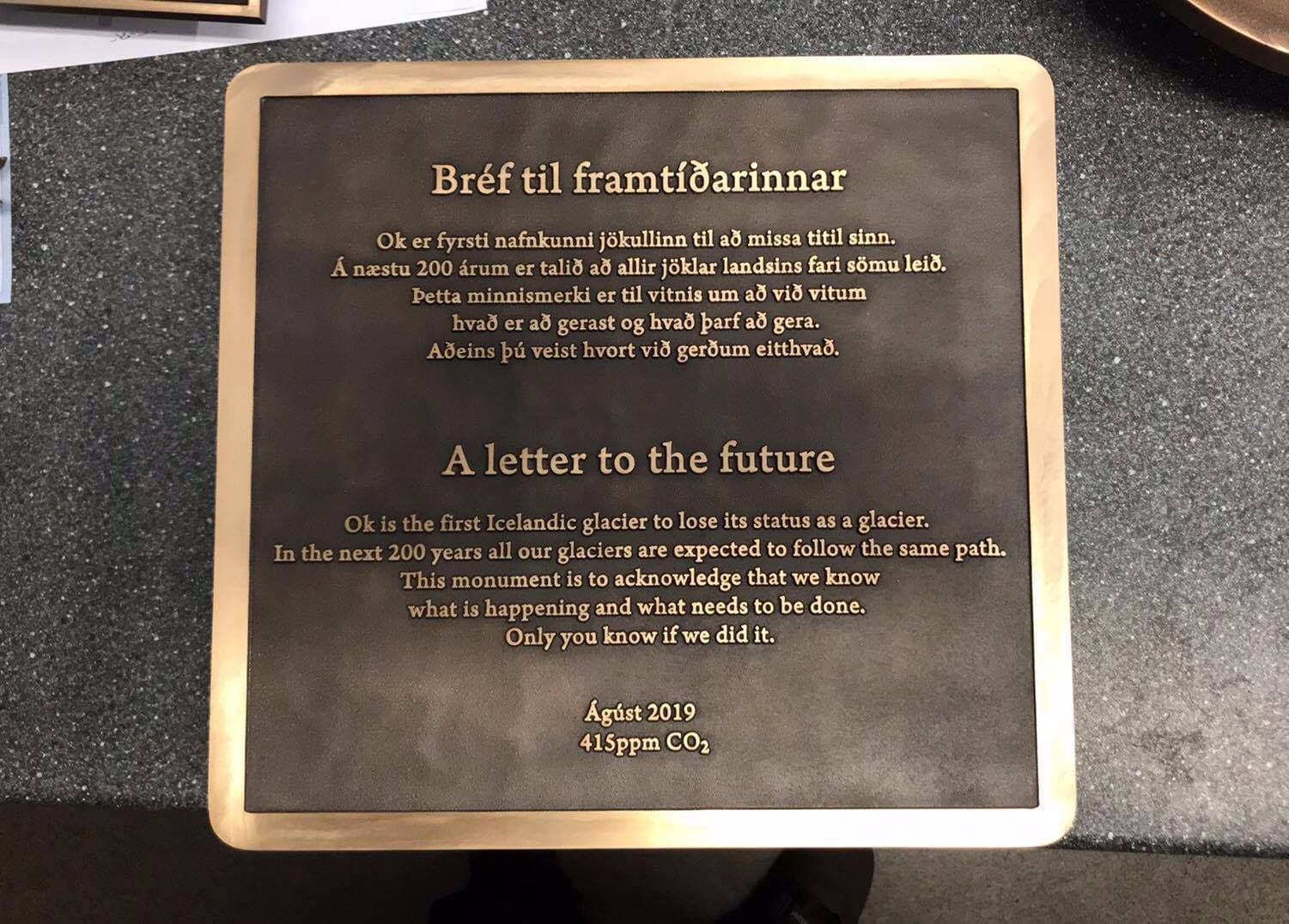

The pair will return to Iceland next month to dedicate a memorial with a plaque that identifies Ok as the first Icelandic glacier lost to climate change. It’s a sobering reminder that the same fate could await the rest of the world’s glaciers within the next 200 years. The plaque lists the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at the time of Ok’s death, 415 parts per million, well above the 350 parts per million limit needed to keep the earth’s climate hospitable for glaciers—and humans. “We know what is happening and what needs to be done,” the plaque addresses future readers. “Only you know if we did it.”

The Houston-based researchers spoke with the Observer about how Arctic ice masses melting thousands of miles away affect Texas.

Texas Observer: What got you interested in this glacier in particular?

Cymene Howe: It started with an anthropological research project that was focused on the loss of glaciers and a dramatically changing environment we’re having in Iceland. I call it the “social life of ice,”—it impacts the way that people understand their landscape and their country and their sense of identity. Iceland is known as “The Land of Fire and Ice” because of the volcanoes and glaciers on the islands. Icelanders have always had in the past a kind of wary relationship with glaciers. They can create these glacial outburst floods, and those can take out farms and homes [with a] flash of really cold, icy water that comes down very quickly.

During the course of the research, we came across a very small news story in the English press in Iceland, maybe four lines, about the loss of Iceland’s first glacier to climate change. We kind of followed up on this little glacier. We interviewed the glaciologist who determined that it was no longer a glacier, and that became the centerpiece of the documentary itself.

Part of what the research is about is recognizing the shift of feeling imperiled by your natural environment, to feeling compelled to protect your natural environment. And in terms of climate change, I think we see that inversion happening more dramatically in places like Iceland, because global warming is affecting the Arctic so much more—about twice as much as it’s affecting the rest of the world in terms of the increase in heat levels.

We’re seeing the impacts of Arctic ice loss with, for example, the historic heat waves in Alaska this summer. But for someone in Texas, this might feel far away. What impact does this glacier have on us here?

Dominic Boyer: We could think of this as being far-flung, but because of the way the world’s cryosphere, or icescapes, are connected to hydrospheres, the water scapes, we are actually all really impacted by glacial melt. In Houston, where we’re speaking to you from, we’ve got sea level rise that is two to three times as high as the average for coastal cities across the world, because the Gulf of Mexico is so shallow and warm. The ice melting in Greenland and Iceland right now is being redistributed across the globe to the Gulf of Mexico. We saw with Hurricane Harvey just how susceptible the coastal area is to those kinds of supercharged storms and even just regular rainfall. Houston had five 300-year floods between 2015 and 2017, and only one of those was a hurricane; the other ones were just normal storm fronts that just dropped huge amounts of water.

What is the symbolism behind creating a memorial plaque for a glacier?

CH: Usually [we build] memorials to a battle or a war or some important historical figure. These are memorials to things that humans have done, and that they feel proud about. And so we want to invert that, in a way—to use this memorial to say, “This is something climate change and humans have also done.” Ultimately, the message we’re trying to convey [is] that this is anthropogenic, this is human-caused. Instead of feeling proud about this particular memorial, we should feel woken to act.

DB: One of our interviewees [in the documentary] told us that memorials are not for the dead, they are for the living. It’s the way that community comes together after a loss, whether it’s a family or village, or whatever scale of human community we’re talking about. We need to act as a human community now at the level of the species, the level of all the nations of the world working together.

What kind of action do you hope this sparks, locally or internationally?

DB: Iceland is doing pretty well—it’s not a big contributor of greenhouse gases. It’s a country of about 340,000 people. It’s a reminder to all of us that we have this natural heritage that is an increasingly precarious situation and will be unless we change our ways. The most important [action we hope for] is that people actually begin to engage on this issue. All of us have a role to play in terms of raising awareness, in terms of demands from our political representatives that they take this issue seriously, in terms of the consumer choices we make.

CH: Iceland is losing its natural landscape so rapidly because of climate change historically caused by big industrial countries like ours.

DB: It’s striking that a place like Texas, which has contributed a lot and profited a lot from fossil fuels over the years, is actually [facing] all of these new kinds of risks. Texas has the highest number of climate-change-related disasters [in the United States], because it gets both drought and floods. Most states get one or the other. We’re lucky to get both here. It’s one of those ironies that the very thing that’s been the lifeblood of the Texan economy for so many decades is actually now what’s making Texas an increasingly difficult place to live, whether it’s because of the heat, or because of the drought, or because of the catastrophic rainfall and flooding.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

READ MORE:

-

Climate Change is Making Texas Summers Worse. Here’s Who That Hurts the Most: Outdoor workers and the most vulnerable Texans — the poor, disabled and elderly — are feeling the brunt of summer’s punishing heat.

-

Trump Administration Report: Climate Change Is Hurting Texas: If greenhouse gasses aren’t curbed, the Texas economy will likely face devastating consequences from climate change.

-

Shallow Waters: In a warming world, the fight for water can push nations apart—or bring them together.

-

Sinking Land and Climate Change Are Worsening Tidal Floods on the Texas Coast: More than 10,000 homes along the Texas coast will flood at least 26 times a year by 2045, researchers say.