“Depression, for me, is having no energy to do anything, despite wanting to,” says Matt Gibson, a top domestic racer who currently rides for Continental team Saint Piran.

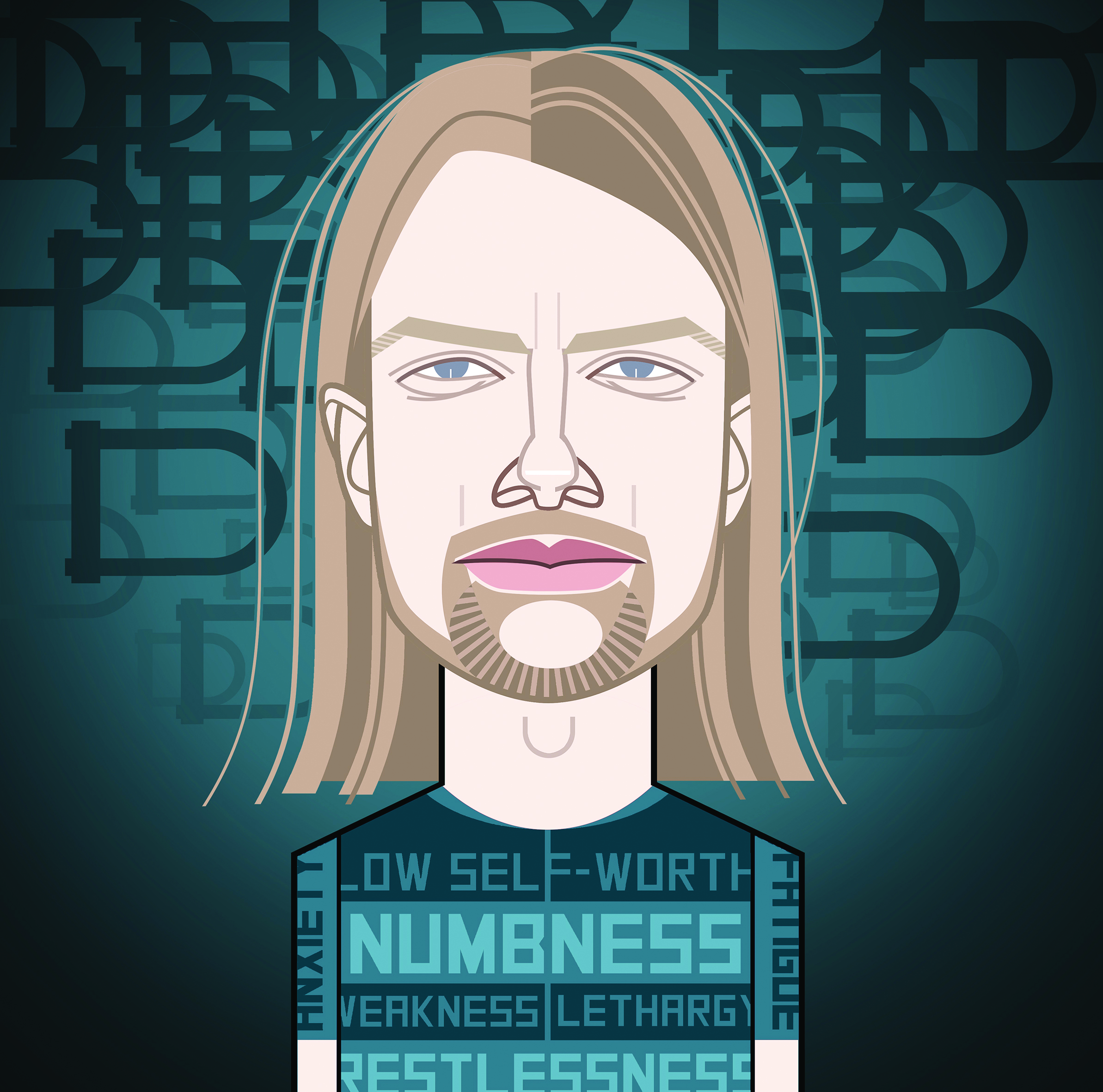

“You feel helpless, worthless, powerless to your own body, and just generally sh*t. You’ll train and try to hit your numbers, but you can’t. You’re lethargic, weak. More than sadness, it’s a feeling of numbness.” The 27-year-old has competed and won bike races around the world, but accompanying most of his accomplishments has been an invisible illness, one affecting 280 million people worldwide.

“When I’m having a bout of depression,” he continues, “I tend to withdraw from any sort of social interaction. Sometimes I’ll force myself out and it does make me feel better, but my default setting is not to reply to any texts, not to answer the phone, and not to burden anyone with how I’m feeling.”

Gibson, who is recovering from a broken leg sustained in the winter, suffers from bouts of depression – as do an estimated 16%, or one in six, of the UK population. A common mental disorder, depression is typified by having a low mood and a loss of interest in almost all activities.

Thankfully, the stigma around mental health has gradually decreased over the past decade, but speaking out can still feel very difficult – particularly for pro riders who are expected to convey resilience. Whether or not cyclists are especially susceptible to depression is impossible to ascertain, but Gibson knows of other professional riders who struggle like he does. “It’s more common than is publicly known,” he believes.

A big problem, according to the University of Bern’s Alexander Smith, is that cycling teams and governing bodies, at all levels, are doing little to address an illness that has become 25% more prevalent since the Covid pandemic. “The IOC, FIFA and a lot of other sporting federations invest a lot into mental health support, both from a preventive point of view for athletes and spectators, and also raising mental health awareness,” Smith says. “Sadly, though, cycling is far behind in this regard, and there is a massive lack of awareness of symptoms and misrecognition.” It’s clear, then, that we must talk about depression among cyclists.

Types and triggers

Alongside anxiety and bipolar (other issues previously covered in this ‘Let’s Talk About’ series), depression is among the three most common mental health disorders. There are different types of the illness: major depression includes feeling extremely downbeat for two or more weeks; persistent depression disorder lasts for more than two years; seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is typical throughout the winter; and postpartum depression can occur after childbirth. Whatever the specific diagnosis, the characteristics are similar: restlessness; fatigue; feelings of guilt and fear; a lack of pleasure in activities that are usually enjoyed; difficulty concentrating; low self-worth; and, in severe cases, suicidal thoughts. Women are almost twice as likely as men to suffer from depression, and young adults between 18 and 25 have been shown to be more at risk than older people.

There is no singular reason behind the development of depression, and it is thought to be a response to a combination of different factors involving the brain’s chemistry, hormones, genetics, and social elements. It has been proven that substance use, chronic conditions, other mental health issues and family history can lead to its onset. Professor Michael Liebrenz, also from the University of Bern’s department of forensic psychiatry, says that the time investment required by cycling, regardless of the level, can put a strain on relationships, and is “another reason why affective disorders like depression are probably more common among cyclists than in the wider population.” He points out that “major depressive episodes can develop without being a reaction to an event.” In other words, there’s not always a trigger. “People look for a specific reason, but sometimes there isn’t one.”

Lack of data

“Anxiety was always prevalent for me as a child,” Gibson says, recalling anxiety attacks in the classroom, “but no one ever took it seriously.” Having begun cycle racing aged 14, he marked himself out as one of the northwest’s brightest talents, and he was selected to British Cycling’s junior academy as a 16-year-old, and then the senior academy aged 18. It was then that depression first hit. “Everything was going really well, and in my second year as a junior I was training with the senior team on the track, and I was being pushed to train harder and harder,” he remembers, “but I knew I was getting fatigued and was overtraining, as I’d only had two days completely off the bike all season. During one altitude training camp in Tenerife, I forced it too much and caught a virus. For the next 18 months I couldn’t perform or train properly, as I was always fatigued, and my ability decreased rapidly.”

Gibson was later diagnosed with chronic fatigue. “I felt like I was completely alone, as no one knew what was wrong with me,” he says. “Without the ability to perform on the bike, the one thing I felt like I’d been any good at, all I was left with was the insecure teenager underneath. Looking back, that was when the first period of depression began.” Nine years on: “There have been periods where I’ve felt OK, but for the most part I’ve not been OK. A lot of the time, you wouldn’t know it. I can fake a smile and hide the emotions,” he says.

Unresolved traumas are often the foundation of depressive episodes. “Things from earlier in my life are the more likely reasons as to why I feel like I do, and cycling has brought up emotions not dealt with from when I was younger,” Gibson continues. “There were certain situations as a child where I felt responsible for the way others felt and for keeping them happy. Coaches and other riders were sometimes sympathetic, but for the most part they’d say, ‘there’s nothing wrong with you, get on with it’. I wish that were the case – I wish I could get on with it.”

In 2019, aged 22, Gibson joined Burgos-BH, a Spanish Pro Continental team, on a two-year contract. Though thrilled to have achieved his childhood dream of turning professional, the reality was somewhat different. “It was a foreign environment that I didn’t fit into and I wasn’t used [by the team] to my full potential. It was a low moment.” He was not the only professional rider suffering from depression. “The environment in pro road cycling, the way riders are chucked from one race to another, is detrimental to their mental health,” he says.

One study after the Tokyo Olympics in 2021 found that up to 30% of athletes reported symptoms of depression in the aftermath of the Olympic Games, and other research has concluded that between 15 and 20% of professional athletes suffer on a year-round basis. But no reliable figures have ever been collected on the number of professional cyclists with depression. “The lack of data on mental health in cyclists is shocking,” says Liebrenz. The professor is calling on cycling’s world governing body to act, and questions surveillance practices such as weighing riders and recording caloric intake multiple times a day. “We need the UCI to step in and to create anonymous data to help our community to stay healthy for the next 30 years, not just the next five years.”

Suffering in silence

It is thought that 60% of people with depression don’t seek help, and thus the true prevalence may be much higher than currently estimated. The secretiveness is no surprise to Gibson. “The feeling of burdening people weighed on me massively,” he says. Speaking out should be encouraged, though, since treatments are available, such as antidepressants, CBT talking therapy and counselling. In 2019, Gibson sought help. “It took me a long time to get therapy because I felt I didn’t deserve help,” he says. “I felt I should have been able to sort through my problems. Symptoms like not getting out of bed or not cleaning the house I was almost embarrassed to admit. The first time I went to the doctor to talk about it, I was petrified and just burst into tears.”

Last year, Gibson started taking antidepressants, as do 8.6 million British adults. “They helped me to train more consistently, but I didn’t feel like myself,” he says. There were other problems with taking the medication, too. “I took them for a year but if I ever ran out, I’d have the most intense depression for a week as my body was withdrawing from taking them. Antidepressants are really useful for starting the process of helping yourself, but not something to take for a long time.”

Therapy has made a huge difference for Gibson. “It’s massively helped me to process the reasons why I feel depressed and helped to give answers,” he says. “It’s become easier to understand my own thought processes and behaviour, and it helps me to plan and put in place strategies that help me to perform more effectively. I really believe that without therapy I wouldn’t still be here.”

Amateurs also affected

Of course, depression doesn’t just affect the sport’s professionals. British amateur rider Max Farrar (not his real name), 28, a cyclist since his teenage years, moved to Sweden in autumn 2019 to complete his university degree. “I was really excited, but I quickly learned that I had so much studying to do and I only left my flat to go to lectures,” he says. “Scandinavian winters are always dark too, and when there is daylight it’s usually grey and miserable.” Farrar believes his struggles were compounded by seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a common form of depression associated with winter. “I experience a dip in mood every winter, so there’s always a risk of a spiral in the darker months,” he acknowledges.

“You can’t force anyone to do anything – you have to support and encourage them, and accept that you may not understand how they feel, and how they are behaving might not correlate with reality. Being there, patient and understanding with them is sometimes enough.

“A lot of people will ask, ‘What can I do to make you feel better?’ Unfortunately, other people can’t fix it for you. For some people it might take a while, and they need to sit it out, get through a low period before putting in steps towards feeling better. It’s very individual in terms of what might help each person.

“Often the best thing you can do is give them time. Once they’re feeling OK, then ask them what you can do the next time they are feeling bad. They’ll be in a better state of mind and can provide clearer answers.”

Farrar returned to the UK when the Covid pandemic began, and his mental health deteriorated further. “That’s when I went to the real depth of it,” he says. “I was finishing my degree remotely, my relationship was breaking down, and I went down a dark hole of not seeing any positive energy in anything.” Farrar knew he was acting irrationally, but could not change course. “I would look in the mirror and say, ‘how could anyone love that or see any worth in that person?’ My view in life is that everyone is valuable, so to not see value in myself was concerning, but I couldn’t change how I felt.” Despite trying his best to exit the negative spiral, nothing worked. “The reason I got so scared is that I was doing everything you’re told to do: I was going on the bike regularly, eating healthy, speaking with people, avoiding drinking, smoking and taking drugs. So why was I feeling so awful? I knew something was wrong.”

In June 2020, Farrar called his doctor and was given a referral to acceptance and commitment therapy, a mindfulness- based treatment that encourages people to embrace their feelings instead of resisting them. “Very quickly it was a success,” he smiles. “I realised that I had been feeling guilty about cycling because my partner was having health issues, and also felt pressure to conform to societal expectations. I was rebelling against the idea of having a perfect, settled life by my mid-20s. Therapy taught me about reframing and understanding, and acting on the values that mattered to me, such as exercising and being outside.”

Following a stint working in Asia, Farrar decided to return to Sweden, and was introduced to gravel cycling. “I immediately fell in love with gravel because it offered me a freedom to get into a state of meditation – something in me needs the simplicity and clarity of a pedal stroke.” He is “in a good place now”, and draws on lessons learned from the therapy sessions every day. “I approach every decision with the question of: does this correlate with my values? Is this going to satisfy my curiosities? Is it going to affect how much I cycle?”

Now living back in the UK, Farrar uses cycling to stave off depression. “I name all of my Strava rides after things I’ve seen,” he says. “It might be trees, animals, a cool building, whatever, and doing so allows me to ensure that I value what I experience. It’s about taking me out of the everyday routine of washing clothes and dishes and meetings, and being in the present. Therapy has changed my life.”

Back on course

Gibson, who is planning a racing comeback this July, is visiting a therapist once again, but feels he is “on a really good trajectory in my life”. He has accepted that his depressive bouts are likely to recur on a regular basis. “I still suffer from periods of low mood and energy, and probably always will,” he says, “but I know I’m gradually getting more able to work around it. It’s about learning strategies, processing my emotions and feelings, and allowing myself time to rest completely.” His current injury has been a moment to pause and reflect. “Feeling like I can be 100% myself has lifted a massive weight off my shoulders. It has reinvigorated my passion for bikes and I think that will show in my performances.”

Gibson and Farrar are not unique or even rare cases – tens of millions of Europeans live with depression. But as these two bravely outspoken riders demonstrate, there are remedies and support networks that can mitigate symptoms and improve mental wellbeing.

For Gibson, a rider who’s won six UCI races in three different countries, his experiences have reassured him that a relaxing bike ride can work wonders.

“When I can’t hit my numbers, it takes me a while to accept it, but I’ve learned that long, easy rides make me feel so much better and help with how I cope with depression,” he concludes. “Being active, outside, enjoying myself, is a huge part of regulating my emotions.”

If you have been affected by anything in this article, free listening services include Samaritans (116 123) and Shout Crisis Text (text “SHOUT” to 85258). The mental health charity Mind can be reached on 0300 123 3393, and the National Suicide Prevention Helpline can be contacted on 0800 689 5652.