The moment that Creed singer Scott Stapp realised the band’s 1999 second album Human Clay had catapulted the group into a rarified realm of success came in 2001 when they were presented with a Diamond certification to mark 10 million sales. Stapp checked out what sort of company the Florida four-piece were keeping, and the U2 nut was shocked to see that Bono & co.’s The Joshua Tree had reached the landmark only a short while earlier. The Joshua Tree had been out since 1987; Human Clay had done it in less than two years.

“That put it in perspective for me,” says Stapp today. “That’s when it was like: ‘Whoa, this is mind-blowing.’ It gave me clarity and perspective on what was happening.”

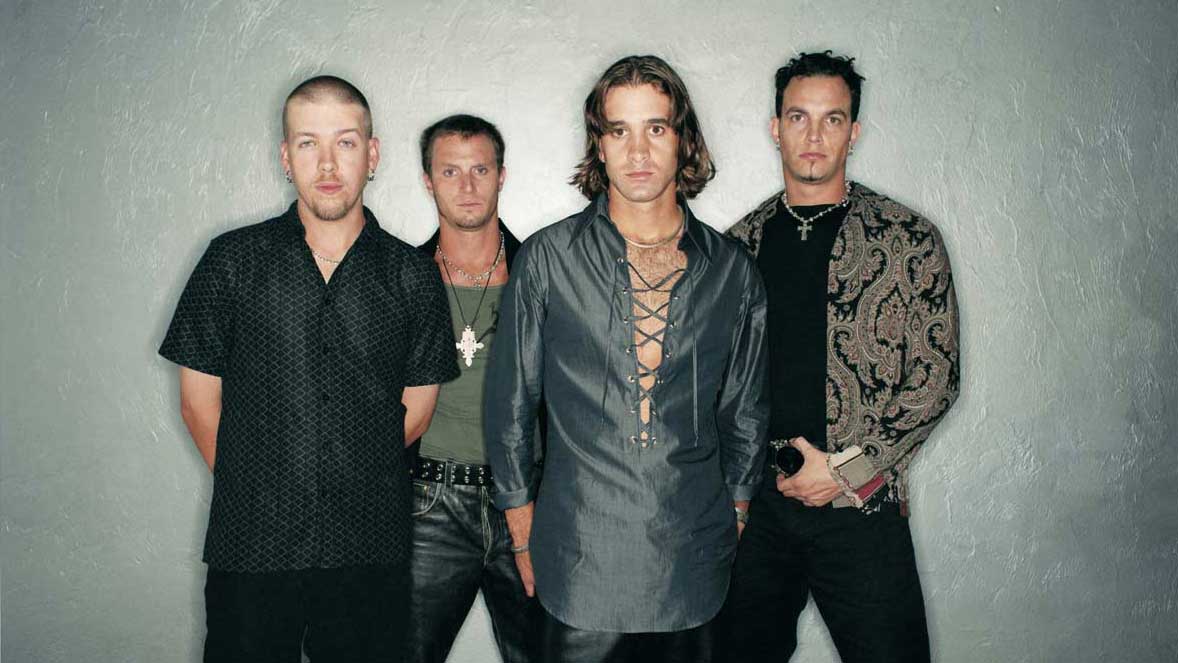

“And what was happening?” you ask? Well, Stapp and his bandmates – guitarist Mark Tremonti, bassist Brian Marshall and drummer Scott ‘Flip’ Phillips – were entering the new millennium as one of the biggest rock bands in the world. Not everyone was happy about it, but we’ll get to that.

Human Clay, which went on to sell a staggering 11 million copies in the US and 20 million worldwide, turns 25 this year, and Creed are celebrating the milestone with an anniversary reissue. And for perhaps the first time in their history, maybe the band feel like they can raise their heads above the parapet without getting a slap.

After a lifetime of ridicule, it has all been coming up Creed recently. A new generation of fans have been making videos to their songs on TikTok, the US baseball team the Texas Rangers and NFL team the Minnesota Vikings have been using their huge hit Higher as an unofficial anthem - the song also cropped up in a high-profile Super Bowl ad for Paramount+ earlier this year – and their Spotify numbers are booming.

It hasn’t just been about looking in the rearview mirror, either – they are back together for their second crack at a reunion since splitting in 2004, and are currently playing some of the biggest shows of their career. No one, especially the four band members who spent their commercial peak getting hit with the critical shit stick, saw this coming.

Back when they first emerged in 1997, Creed’s mix of bombastic metal riffs, emotive yearning and baritone-voiced anthems won big. They had arrived at the precise point that legions of American rock fans needed something to fill a grunge-shaped hole. In Stapp they had a frontman who looked like he’d just stepped out of his own calendar, topless, pouting, but with feelings. If grunge was pale and pasty, here was the tanned cavalry. MTV breathed a sigh of relief; Creed had no idea what they were swaggering into.

“We were just college kids from Tallahassee, Florida,” Tremonti recalls. “We put all our money together from college to buy gear to go on tour and start from the bottom. I saw people say in the press: ‘Oh, this is some corporate put-together band’! It couldn’t have been farther from the truth. We were a college band that got signed to a brand-new label, and none of us knew what we were doing. We got lucky to be surrounded with a bunch of hard-working people that wanted to make this thing happen.”

Human Clay had its roots in the surprise success of the band’s 1997 debut My Own Prison. Finding themselves fast-tracked to headliner status, they realised they didn’t have enough songs to fill a 90-minute set.

“We began writing on the road so we’d have more songs to play live,” Stapp recalls. “I remember us having the confidence to not only write during sound-check and in hotel rooms, but then play them live for an audience before they were even recorded. I don’t know if you could do that today with everyone recording things, because the songs would get out. But I think that shows the confidence we had in ourselves to write and create and then play it for a live audience. It gave us a litmus test on how songs would react.”

Some songs were even written during gigs, which is how their swaying rock singalong Higher came about.

“I told the guys: ‘Let’s write something live,’” recounts Stapp, an earnest and considered talker. “At the time, I was exploring stream-of-consciousness and dreaming and awakening in your dreams. That song, the chorus was a freestyle.”

On another occasion, he remembers, he’d just received news that he was going to be a father for the first time, and walked into the venue at Penn State University to the sound of Tremonti doodling with the plaintive lick that would become the intro to their Grammy-winning hit With Arms Wide Open. “I had all these emotions running through me, and I liked what Mark was doing. We had such creative chemistry and were in tune with each other. When he started playing that, I was just expressing my feelings in the moment.”

By the time Creed set up a studio in a hired house on the outskirts of Tallahassee ready to record, everything was ready to roll. Life on the other side of Human Clay would bring huge commercial success, fame, money, mansions, splits, alcoholism, drug addiction, breakdowns, turmoil… and eventual reconciliation. This was the calm before the storm, the group getting down to work with producer John Kurzweg and revelling in the free-flowing vibes surrounding them.

“The most beautiful and wonderful thing about that recording experience is it was so much fun,” Stapp remembers.

“The vibe was awesome,” agrees drummer Phillips. “Everybody went in with a lot of confidence in the way we were performing those songs at the time. We had a very unified vision of what we wanted to achieve.”

Tremonti remembers sitting in the studio with Kurzweg and listening to a playback of Higher and thinking to himself that they were onto something. It didn’t take long for him to be proved right. Tremonti and his wife were on their way home from furniture shopping the first time he heard Higher being played on the radio.

“They had mentioned something about sophomore slumps,” he says, “but when they played that single they said: ‘Alright, it appears Creed is not going to have their sophomore slump with this song.’”

“It was a different time as terrestrial radio was the only real music outlet back then,” opines Marshall, explaining that they put in the hard yards when it came to promo, hauling themselves across the country for radio sessions, interviews and in-store appearances and eventually noticing that it was paying off. “We’d pull up to a gig and see a line outside the venue and be like, ‘This is gonna be a sold-out night’. That was real eye-opening.”

After the success of Higher, the only way was up. Human Clay, released in September 1999, entered US charts at No.1 and stayed on the Billboard 200 for a record-breaking 104 weeks.

“It was when we started playing arenas that it was like: ‘Alright, this is the big time, this is what I’ve dreamt about my whole life,’” says Tremonti.

Further evidence of the band’s lofty new status came when Tremonti took receipt of a new guitar: “I remember specifically being in an arena and opening up a guitar case that had my signature guitar, my PRS Tremonti model,” he recalls in awe. “That was one of those peak moments in my career, like, ‘I can’t believe I have a guitar with my name on it with the best guitar company in the world.’”

For Tremonti, it’s a memory up there with the time that Eddie Van Halen took him under his wing when Creed supported Van Halen for two nights in 1998.

“I remember Eddie going: ‘Hey, who’s the guitar player?’ and I raised my hand,” Tremonti recalls. “He’s like: ‘Come here,’ and he showed me his whole guitar rig and how everything worked. He’s like: ‘What colour do you like?’ I said: ‘Black.’ The next day, he brings me a black guitar, the Wolfgang guitar. It’s one of my prized possessions.”

As Creed’s resident metalhead, Tremonti was the member most thrilled that they were getting to play alongside some of his heroes.

“Being able to share the stage with Metallica few times was epic for me,” he says. “There was a couple of festivals we did where I remember one day we played in between Sepultura and Ministry. Those moments were killer for me.” He reflects on it for a second. “At the same time, I was like: ‘I don’t know if we’re the type of band that fits after Sepultura!’”

Human Clay continued to fly off the shelves, and Stapp says their lives were completely transformed.

“I went from living in an apartment sleeping on a mattress to, within two years, playing arenas, being on television. From playing in a bar with just our friends showing up, driving a van and a trailer around and unloading gear, to having tour buses, semi-trucks,” he says. “Everything happened so quickly. All of it was a pinch-me moment.”

“I just assumed it happened to all the bands,” Phillips says, laughing. “I assumed that everybody got to do these really cool video shoots and go to these award shows and perform on Letterman or Leno. I just thought that was part of the process. It wasn’t until after the fact that I looked back on it and was like: ‘Wow!’”

However, the backlash was on its way. Stapp still has their magazine front covers and features framed on his wall, such as the Billboard article that proclaimed: “Scott Stapp is this summer’s rock’n’roll saviour”. He struggles to get his head round how quickly feeling turned against them.

“It’s not part of your rock’n’roll dream,” he says. “We went from the press showering us with love, where they’re like: ‘Creed saves rock’n’roll!’, to the backlash. It was from the press. It wasn’t from the fans, they were showing their support by buying the records and the tickets. It was hard to understand, like: ‘Wait a minute, on one hand we’re continuing to reach people and selling out multiple nights at arenas, but then why is this happening, what did we do?’ It hurt. I can’t say that I didn’t feel it in my heart and wish that it was different. I can only speak for myself, but I definitely didn’t handle it well.”

The immediate impact of the onslaught, Stapp says, was that it placed a rather large chip on his shoulder. “You can walk into situations with the press and the media and anyone else who jumped on the bandwagon, with a sense of frustration,” he explains. “I think it could give off a different impression than who we really were, who I really was prior to that, because your defences are up and you’re feeling a little bit betrayed. It definitely had an impact on me.”

Tremonti says his outlook on the avalanche of negativity that was directed at Creed has changed over time, mellowed by his experiences with Alter Bridge, the band he formed with Creed members Marshall and Philips along with guitarist and vocalist Myles Kennedy in the aftermath of Creed’s initial split.

“All the critics love Alter Bridge, so I’ve been able to live on both sides of the fence,” he reasons. “I was in one band that sold millions upon millions of records and had hate and love for the band, and I was in a band that everybody seemed to love but we didn’t sell the amount of records Creed did. I realised in the end that if you want to have huge success you’re gonna have a huge amount of haters, no matter who you are.”

Tremonti thinks it was kickback for how ubiquitous the band had become. “We were shoved down everybody’s throats. You couldn’t turn on the radio without hearing Creed. It was everywhere, so if you liked it at first and you heard it too much, you started hating it.”

It didn’t take long for all the external antagonism to generate hostilities inside the band. Marshall departed due to “personal and professional differences” in 2000, and the group made one more record, 2001’s Weathered, before disbanding in 2004.

“We were all young, we went through some growing pains,” says Philips. “Communication was a key thing we missed at some point. We had this amazing ascent, and then it all fell apart just because we couldn’t get on the same page with each other.”

“I’d say one of the reasons why we split up was just the pressures of not being able to stop,” reckons Tremonti. “Once the machine was turned on, it couldn’t stop, it was always: ‘We need this, we need that, we need it here, we need it there…’ There was never really a lot of breathing room. And when personalities within the band start clashing, that pressure from the outside amplifies it a bit.”

“I wish I could go back and do it again, with the wisdom and experience I have now,” Marshall says. “I wish I could do some things differently. I think staying grounded and communication, that’s a big thing, staying true to yourself.”

Two decades on, they’ve been granted a second chance. It was at the beginning of 2020 that Stapp and Tremonti broke the ice over the phone after the two hadn’t spoken for a long period. The guitarist had just returned from playing the cruise festival ShipRocked with Alter Bridge, and suggested that something similar could be an option for Creed.

“Scott was all about it, then covid happened and everything got shelved,” Tremonti says. “It took a long time to plan all this stuff.”

The band’s cruise comeback set sail back in April this year with two sold-out trips, and all the tickets for a similar voyage in 2025 have already been sold. Before that one, though, they’ll embark on a US tour that has sold more than they did at their peak.

“My manager called me up, and going through the markets he’s like: ‘Indianapolis, 18,000… Tampa, 17,000 tickets, 20,000 tickets…’ It’s nuts. It’s very exciting.”

When they looked at the data of ticket buyers for the shows, Tremonti reveals that the biggest age group was between 25 and 35.

“Those people would’ve been babies [during Creed’s initial run],” he enthuses, “so it’s a whole new generation for us. I think it has a lot to do with the social media stuff, people who’ve seen it on TikTok or people who’ve seen all these sport teams playing our songs, their parents talking about it, who knows? We’re glad to be able to play for a whole new audience.”

That fresh batch of diehards includes Tremonti’s own children.

“My kids have always lived in the house that Creed built and they’ve never got to see the band,” he says. “They’re coming out with me for the first three weeks of the tour and they couldn’t be more excited.”

“What’s going on right now harkens me back to as it was happening so fast in 98/99 all over again,” says Stapp. “It’s an incredible ride, and I’m feeling such joy and fulfilment. It’s almost like a redemptive feeling with what’s happening right now.”

If it’s to last, though, they’ll need to rectify what went wrong during their first crack at a reunion, in 2009, a coming-together that resulted in their fourth album, Full Circle, but ended up petering out in 2012. Stapp still isn’t sure why it went awry.

“I’m kind of at a loss [to explain it], because my heart was in the right place,” says the singer. “And it’s in the right place now. But, to answer it honestly, I think there were certain things in my life at that period of time that I needed to weed out and get rid of which could enable me to be the best version of myself. I think that would be the only difference between then and now.”

Tremonti thinks the trick to staying together comes down to everyone being open with each other about what else they’ve got going on musically outside of Creed.

“I think we all have to understand that we’ve put a ton of work into our other bands and projects and they can’t just get thrown away because of this,” he says. “Of course, this is doing very, very well, but that will never mean that, come next March, I’m not getting in the studio with Alter Bridge, or I’m not releasing a Tremonti record. Scott’s record Higher Power is out and he’s touring for that record right now.

"We’re all doing things, which is great. I think that keeps Creed healthy. Everybody needs to know: I got my project, you got your project and then we come back with Creed. Stapp says the relationships between the four band members are slowly getting back to base, returning to something that resembles what they were like when they started the band.

“When we first got together, we were all best friends,” he recalls. “We were spending holidays together, situations that were going on in our personal lives, whether it was hurt or a break-up or the passing of a loved one or whatnot, we were all in that together, emotionally and as friends supporting each other.”

It’s a sense of camaraderie that the frontman is desperate to get back to. “I’m beginning to see and have seen signs of that now. It’s a very encouraging thing. I want to cultivate that and nurture that. I think that’s what could keep this band moving forward.”

The 25th Anniversary Edition of Human Clay is out now via Craft Recordings.