In the autumn of 1987, Tony Martin received a phone call from his manager, inviting him to take a drive around the pair’s native Birmingham. At the time, Martin was the frontman with a local band called The Alliance. They had recorded a session for BBC Radio’s The Friday Rock Show and, thanks to a development deal with Warner Brothers Records, recorded an impressive demo tape that was generating a little below-theradar attention.

Martin’s manager, Albert Chapman, was the owner of The Elbow Room, a rough-and-tumble nightspot on the city’s Aston High Street. Chapman had been a schoolmate of some of the members of Black Sabbath, and took on the role as their tour manager during the band’s rise to international success during the mid-70s. Consequently, Chapman knew almost everybody on the rock scene, especially in the Midlands.

On the afternoon concerned, when Martin enquired about their destination, Chapman remained evasive. “So, we pull up at this house, Albert knocks on the front door,” Martin says now, “and when it opens, fuck me, there stands Tony Iommi.”

Backtracking just a little, Chapman had put forward the name of his young charge a couple of years earlier, at a time when Sabbath were having issues with their latest frontman, former Trapeze and Deep Purple bassist/vocalist Glenn Hughes.

“I don’t know what those issues were,” Martin insists. “All I remember is that when Albert said: ‘I’ve put you up for that job. Are you interested?’ I replied: ‘Whaaat?!’ I couldn’t sing like Glenn Hughes – nobody can. But they [Sabbath] put me on standby. And it scared me to death. In the end the issues with Glenn were sorted out and they released the album Seventh Star.

“I thought nothing more about it, but later on Albert called back and asked: ‘Do you want to have a go with the guys?’ I thought: ‘Fucking hell, this is a bit mad’. But he was serious.”

On the day in question, despite the previous conversations, Martin had zero knowledge of who he was about to meet. “It had all been a bit cloak-and-dagger,” he says, smiling. Chapman and Martin were invited in for a chat, and before too long the singer attended an audition in London.

“I was asked to sing The Shining, which became the opening song on The Eternal Idol,” he recalls, “and right away I was told: ‘You’ve got the job.’ But before it soaked in they added: ‘The album has got to be finished in seven days.’” My response was: ‘Okay, I’ll give it a go.’ And that was my introduction to being in Black Sabbath.”

Having signed on the dotted line, Tony Martin became enshrined as a member of one of the most important hard rock and heavy metal bands of them all. Unfortunately, however, in spite of all his efforts Martin was not destined to receive all that he signed up for.

Over the next decade the singer would experience all that life in a once iconic but now ailing band could throw at him, including five albums, two sackings and multiple world tours. Martin went on to become Black Sabbath’s second-longest-serving lead singer, after Ozzy Osbourne, but his tenure brought its share of uncertainty, frustration, and heartbreak.

Within minutes of talking to the gregarious, straight-talking and likable Martin it becomes apparent that he really doesn’t give a shit about negativity. Not any more, anyway. His time fronting Sabbath was about seizing an unexpected opportunity. A chance to be creative, in defiance of what seemed like pretty insurmountable odds.

Which is exactly what happened. Incredibly, the new-look band went on to create some of the best albums in Sabbath’s sizeable catalogue (which have now been retooled as the four-disc set Anno Domini 1989-1995).

By the late 80s, Black Sabbath had descended into a shit-show. Ronnie James Dio quitting to form his own band began the slippery slope. Former Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan sang on the love-or-loathe Born Again album, and fronted the band on a tour that inspired Spinal Tap, with its outsized Stonehenge stage prop, and had ELO’s Bev Bevan on drums. Factor in Gillan’s reluctance to learn the lyrics, and a disastrous sleeve design of a baby with claws and horns, not to mention the imminent reunion of Purple’s Mk II line-up, and Sabbath now resembled the proverbial house of cards awaiting a stray gust of wind.

Martin had entered the frame because American singer Ray Gillen, a replacement for Hughes during a US tour for Seventh Star that was abandoned due to poor ticket sales, had walked out during the recording of Sabbath’s next album, The Eternal Idol, to join guitarist John Sykes in Blue Murder.

Depending on whether or not you include former male model David Donato (whose appointment was announced and then rapidly cancelled after he had told the press: “I always had a [mental] picture of what the right singer in Sabbath should be – and it was me”), Jeff Fenolt of Christian rockers Joshua (rumoured to have been hired and fired just as speedily) and co-founder Ozzy Osbourne (who returned for a disastrous, drunk showing at Live Aid in Philadelphia), Martin was either the third, fourth or fifth lead singer in Black Sabbath since Ian Gillan waved goodbye in March 1984.

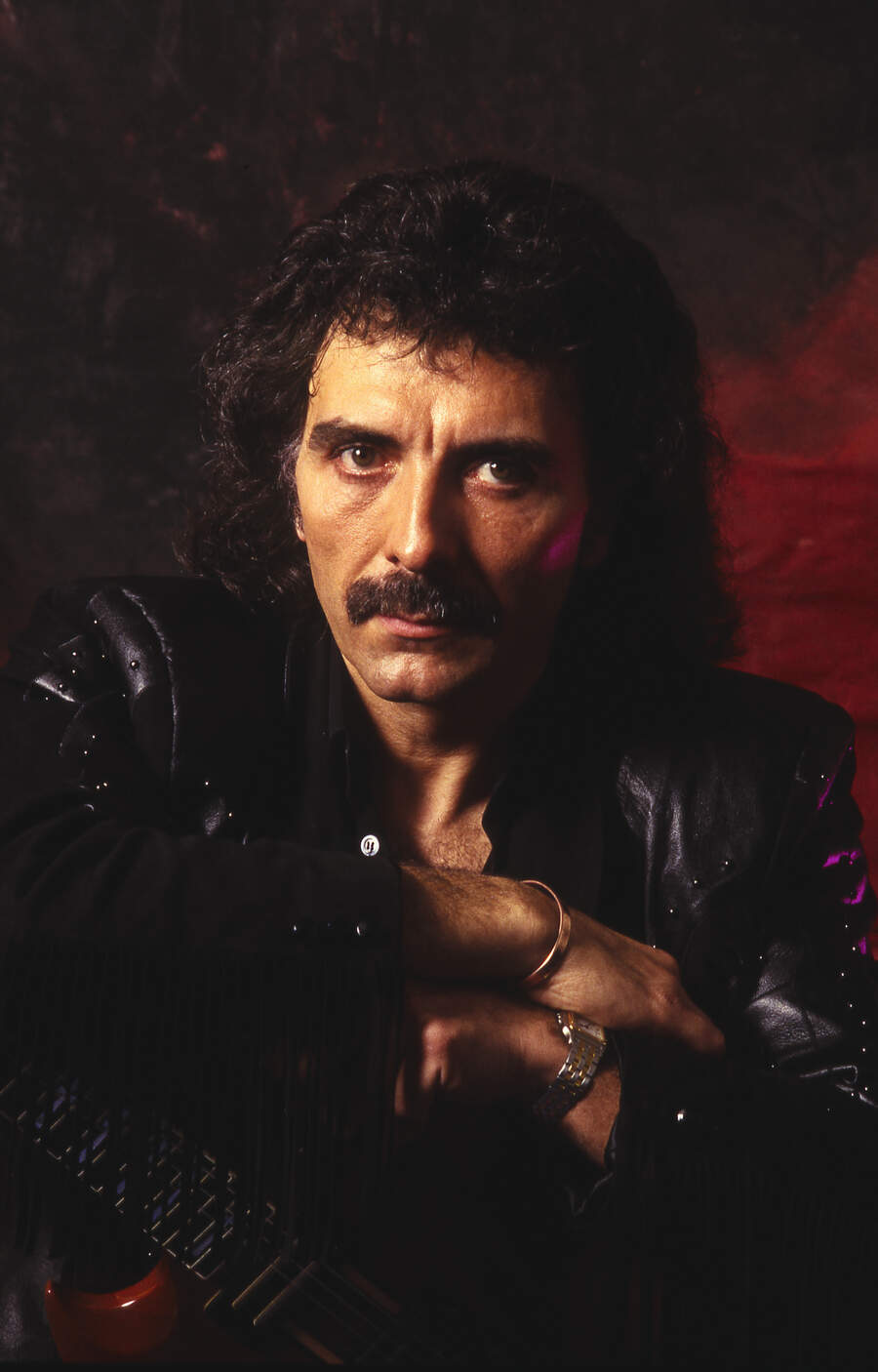

When asked to sum up the aforementioned half-decade in the history of Black Sabbath, Tony Iommi, the last man standing from the classic era, is momentarily lost for words.

“It was chaos,” he eventually replies, laughing. “Just chaos. When somebody left, fine, you bring somebody else in. And when they go, you do the same thing. After a while it gets pretty tedious, but what’s the alternative?”

Sabbath concluded their more than five decade-long career with a sold-out world tour, ending in Birmingham in February 2017, and the band were inducted to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2006. It’s strange to think of them as an underdog, but by the mid-80s that’s what the group had become. And yet, amid the chaos around him, Iommi managed to lead the band towards the creation of some albums that fans still rank among their finest.

“I really love the stuff we did back then with Tony Martin and Cozy [Powell], but it was a frustrating time,” Iommi states. “People had to really try to accept what we were doing. And although it was a great band and we had some really good music, those albums didn’t really catch on. As the man running [the band], I found that difficult.”

In his autobiography Iron Man, Iommi reveals how a previous manager had left the band with huge tax problems. A decaying relationship with Sabbath’s long-time label Vertigo was another cause for near-perpetual sense of firefighting.

“Ever since I’ve been in this business it’s been like that,” Iommi says. “There were problems pretty much since day one. You just have to believe in yourself and try to see beyond those situations. Had I not done so, then I’d have packed up long ago.”

Did he come close to packing it in?

“No. As I say, there were always awful things to contend with, life is like that,” he shrugs. “It’s the thought of keeping things going and getting to the next level that drives you on. You give in or fight through it, and I wouldn’t give in. That’s part of my character, one way or another I always want to carry on.”

As much as joining Sabbath represented a great opportunity for Tony Martin, looking in from the outside it was obvious that the band were in a constant state of chaos, and yet the singer insists that there was no trepidation. “None at all – I didn’t have time to think!” he says, grinning. “I knew they didn’t have any money, Albert had warned me, so I went in and did what needed to be done.”

Martin provided Iommi with the stability he needed. With Ray Gillen’s voice wiped from the tapes, the newcomer soon proved his worth.

“Albert Chapman was my best friend, we’d been at school together, and he was managing The Alliance,” Iommi recalls of the introduction to his new lead vocalist. “We had reached a point with Ray Gillen where there was a problem, and Albert reminded me about Tony. He was great. The guy could really sing, and once he was on board things grew from there.”

Although later on he would supply lyrics, this time, with songs already written, Martin was relieved to ease himself in gently by simply singing what he had been told. When it came to live shows for The Eternal Idol, Iommi remembers that Martin was thrown in at the deep end.

“It was a huge responsibility for Tony,” he acknowledges. “He was so green. Following Ronnie and Ozzy, and Gillan really, was a bloody hard challenge – especially in front of a Sabbath crowd. It was difficult for Tony, and I expected him to come up to the mark. Because I was so busy thinking about pushing forward, I didn’t really consider the fact that he was now in a totally different world. But he stuck with it, and he got much better.”

Martin’s first gig with the band was in the Greek capital Athens. “My debut was supposed to be a festival in Bristol, but nobody turned up and the promoter went bust,” he recalls.

Being on stage with Sabbath was far from a fun experience for Martin. “Mate, just assume that throughout my entire career with Sabbath I was shit-scared,” he says with a smile. “It never let up. Those guys already had twenty-five years of experience. As much as I learned, I was never going to catch them up.”

Iommi doesn’t recall whether or not he put an arm around Martin’s shoulder in a fatherly way to reassure the newcomer that things would be fine.

“I hope I did,” he ponders optimistically. “But you’re going back thirty-odd years.”

“Actually, Tony didn’t do that at all,” Martin says, laughing, although without a trace of animosity. “I was left standing alone in the dark, trying to match up to these iconic singers that had gone before. I had no idea what I was doing, though I knew my voice was alright.

“They would say with the next album we’re going to do this or that, and I’d reply: ‘What? I’m going to do another one?’ So I guess they must have liked what I was doing.”

Another cause for uncertainty in Martin’s mind was the never-ending speculation that he was going to be replaced by a returning Ozzy or Dio: “I was having to constantly read between the lines to find my position in the band. It was a perpetual learning curve.”

Sabbath had two managers, who often didn’t talk to one another. Things were so shambolic that for the shooting of a video for The Shining, Terry Chimes of The Clash guested on drums, and he band roped in a now-forgotten guitarist they’d never even met to mime the bass parts. The Eternal Idol reached No.66 in the UK, and in the US stalled at No.168.

Artistically speaking, Idol represented a step up from unbalanced predecessor Seventh Star, which Iommi had sought to release as a solo album, but commercially the stats were massively disappointing. Almost two decades after Sabbath’s self-titled debut, their label Vertigo dropped the band.

Undeterred, Iommi signed a new four-album deal to join an eclectic roster of the independent label I.R.S., run by Miles Copeland. One of the industry’s true mavericks, Copeland was also the manager of The Police (and brother of their drummer Stewart), having learned his craft through looking after Wishbone Ash.

“Miles is an interesting person, very noisy and loud,” Iommi says, laughing. “What I liked was that he told me: ‘You know what to do… just do it and the rest is up to me.’ We had artistic freedom. We didn’t need millions of quid, just somebody to get behind us.”

It speaks volumes of the complicated nature of this era in Black Sabbath’s history that all five of their albums with Martin cannot be neatly tied up with a bow and presented as one. As the band’s swan song for Vertigo (Warner Brothers in the US), The Eternal Idol is not a part of the new boxed set.

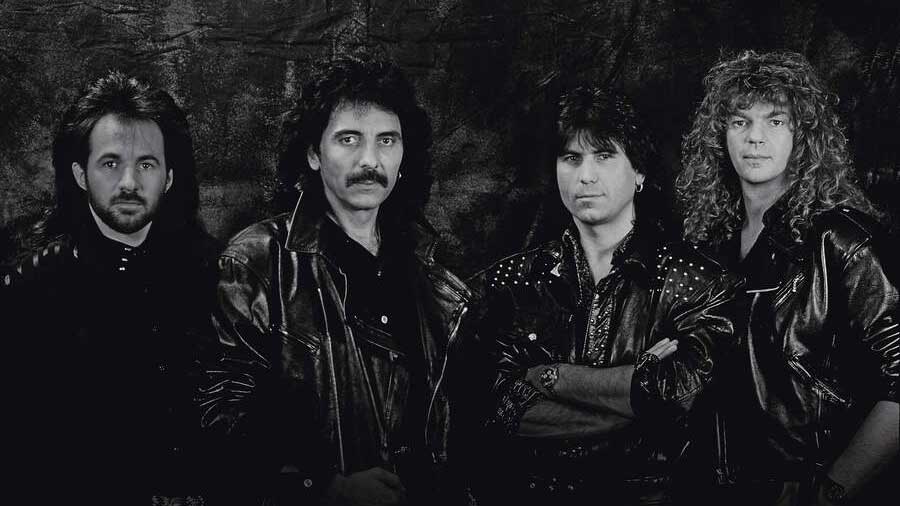

For the next album, Iommi put together what he hoped would be a more solid line-up of himself, Martin, faithful keyboard player Geoff Nicholls, drummer Cozy Powell and bassist Laurence Cottle. Iommi had wanted to work with Powell for many years, and after leaving Gary Moore’s band the former Rainbow, Whitesnake and Michael Schenker Group the drummer happened to be a free agent.

“Getting somebody credible like Cozy was a great boost,” Iommi says enthusiastically. “This was somebody who had seen everything and been through it all, as I had. When Cozy stayed at my house, we’d be up late half-pissed writing songs on a cassette, and then laying them down the following day.”

Although jazz and fusion bassist Cottle played on the session, led by Iommi and Powell, he left once the recording was complete.

With original bassist Geezer Butler on the verge of rejoining, only to change his mind, it was Powell who proposed his former Whitesnake bandmate Neil Murray, fresh out of Japanese hard rockers Vow Wow, to complete the rhythm section.

“I wasn’t overly familiar with Neil, but once I heard him play, that was it – we were off!” Iommi exclaims. Given Murray’s background, which included a stint with prog-jazz-rockers Colosseum II, he was perhaps not an obvious choice, and Murray says that while he was comfortable in the role, covering “the complicated bits and pieces” played by Cottle on Headless Cross and also remaining faithful to Geezer Butler’s playing on the earlier Sabbath material was “a bit of a juggling act”.

There was also the matter of the dark subject matter of Sabbath’s songs. “Certain lyrics didn’t really appeal to me,” Murray says with a chuckle. “But the same had also been true of some of mister Coverdale’s songs.”

With budgets for everything, including producers, now under scrutiny, the ‘new’ Black Sabbath found themselves staying in far smaller hotels than previously, although the resulting levels of camaraderie made the quartet a tough, self-sufficient little unit. “Sabbath felt more like it had done in the early days,” Iommi reflects. “It was a real band.”

As a lyricist, Tony Martin came into his own on 1989’s Headless Cross. Nothing to do with Satanism, the album’s title track took its name from part of the village of Redditch in which he lived. “It told the tale of a plague in the 1600s,” he explains.

Full of high-quality songs including its tense, memorable title track, Devil And Daughter and the brooding When Death Calls, which featured a guest guitar solo from Iommi’s good friend Brian May,

Headless Cross put Black Sabbath back on the map. In Britain it fell just short of the Top 30. In the US, where the band complained bitterly of being unable to find it in the stores when they were on tour there, it narrowly missed making it into Billboard’s Hot 100.

“We had started all over again, but Headless Cross really boosted us,” Iommi says proudly. “People began to respect us once more.”

All the same, it’s vital to remember the extreme bad blood that simmered at the time between Iommi and Ozzy Osbourne, who since being sacked by the band in 1979 had become a superstar, especially in America. Consequently, when Sabbath began touring the US for Headless Cross, the Osbourne set-up used every trick in the book to derail them. “Each night, Sharon put Ozzy in the same cities that we were booked to play,” Martin remembers. “They wanted to split the fans, and it worked.”

After just eight dates, Sabbath’s tour was cancelled due to poor ticket sales. “I can’t state for sure that [the ploy] was calculated, but they were powerful enough. They didn’t like the fact that we were touring and it was being sort of successful.”

Continuing the excellent work begun with Headless Cross, in February 1990 the band began recording the fourteenth Black Sabbath album. Cozy Powell had suggested it should be titled The Satanic Verses, in honour of Salman Rushdie’s controversial book. For obvious reasons this idea was quickly overruled. Tyr, with lyrics based on Norse mythology, was released in the summer of 1990.

“Headless Cross was a crash course in English history, so Tyr was Viking history,” Martin explains. “I had lots of themes in my head, like Samurai warriors. Every culture has its dark side.”

“It was hard for Tony,” Iommi says, “because Ozzy had done his thing and Ronnie also had his own style. After those two we needed to sing about other things than devils and those areas that Ronnie took us into,” he points out, adding with a chuckle: “Death was mentioned a lot.”

This time Sabbath did make it into the UK Top 30, although in the US Tyr failed completely to chart. Nevertheless, Iommi felt quietly confident that momentum was building.

“We had enjoyed making both albums, and we toured, everybody knew what to expect of each other,” he recalls. “We were getting things done.”

Bassist Neil Murray raises a valid point: “As good as things were musically, it was difficult to ignore that Sabbath were still seen as Ozzy, Tony, Geezer and Bill. No other permutation could exist – particularly in America. In some places that we went, nobody had broken the news that the lineup had changed.”

But the ‘new’ Sabbath fought hard. In an interview of the era, Cozy Powell told RAW magazine: “I always believed this band to be far above the rubbish that is written about it. [Before the previous two albums] Black Sabbath’s stock with the press couldn’t have got any lower. A lot of the fans still believed, but they needed to be convinced. We are getting stick for calling ourselves Black Sabbath, but it’s a question of believing in something and maintaining that it’s worth keeping.

“The other camp would prefer Black Sabbath to finish, so they can get on with their own careers and make a bit [of money] out of it,” Powell continued in a reference to Ozzy Osbourne and co. “But unfortunately for them we’re not about to go away and die that easily.”

Those comments brought swift rebuke from the Osbourne camp, with Ozzy faxing an extraordinary ‘open letter’ to RAW magazine, sarcastically addressed to ‘Mr Black Sabbath And His Three Droogs’, in which each band member was viciously rebuked one by one.

To Iommi he retorted: “I don’t care what lineup you have, you could have anyone from Dio to Pavarotti and it will never be Sabbath. Don’t belittle that band, Tony, move on.”

Having defended their use of the Sabbath name, Powell was told: “Try pushing that drum stick from your asshole so you can think clearly.”

Addressing Neil Murray, Ozzy warned: “Get ready for your new gig as Geezer Butler’s bass roadie”.

Ozzy claimed to be unable to recall Tony Martin’s name, before concluding: “I would love to say all of this to your faces, pussies, so call me anywhere anytime.”

Reminded of the fracas 34 years later, a milder and more mature Iommi is keen to sweep it under the carpet. “Wow… I don’t remember that,” he replies cautiously. “There was bad blood, but it’s water under the bridge. Ozzy and I have gone through so many things. I played on his last album. Me and Oz are in touch every week. The [positive] way things turned out [between us] is mad, really.”

Despite Powell’s feisty defence of Sabbath’s continuation, following the touring for Tyr in 1992 Ronnie Dio was invited to return for what became the Dehumanizer album. It had taken two and a half years for Tony Martin to feel like a part of the group, and now, without warning, it was over.

“I was devastated,” he remembers. “This was something I hadn’t expected. I had thought we were doing alright.”

Martin’s sacking affected his mental health. “I just withdrew from music for a couple of years,” he says sadly.

As much as Iommi had fought against the move, Cozy Powell was booted out of the group by Dio. Powell had declined to play with Dio after the pair’s spell in Rainbow, and now, daggers drawn, the singer held all the cards.

“I remember Cozy going, ‘If that little c**t says anything to me, I’m going to smash him in the face,” Iommi wrote in his book Iron Man.

Following a bizarre accident in 1991 when Powell’s horse collapsed of of heart attack as he exercised it, breaking his hip and putting him out of action, Dio offered the drum stool to Vinny Appice, Sabbath’s drummer on 1981’s Mob Rules album. For Dehumanizer, bassist Geezer Butler also made a surprise return to the band. He had jammed with Sabbath at a gig at London’s Hammersmith Odeon at the end of the Tyr tour, and it was Neil Murray who suggested that Butler returning to the line-up would be a good thing.

“I wasn’t wishing I was out of the band, but when Geezer played Black Sabbath and Paranoid with us, the audience reaction made that very obvious,” reasons Murray, who, along with Cozy Powell (who died in a car crash in 1998), would join Brian May’s solo band. “They wanted two of the four originals instead of one.”

Produced by Mack (of Queen fame), Dehumanizer sold well, thanks largely to the inclusion of the song Time Machine in the soundtrack to the film Wayne’s World.

It took two years for the reunion with Dio to come to an end, but when it did it was in spectacular fashion. Sabbath had agreed to play two shows in California as a part of Ozzy Osbourne’s retirement, but when Ronnie dug his heels in and refused to appear (“I have more pride than that, I’m not supporting a clown”), Judas Priest frontman Rob Halford stepped in. A reunion of the classic Sabbath line-up appeared to be on the cards, but it didn’t happen. Instead, Iommi and Butler reached out to Tony Martin.

In fact, Martin claims to have been present in the background during the Dehumanizer sessions, which were slightly troubled: “Tony had called me up and said: ‘This isn’t going too well with Ronnie. Do you fancy coming along and having a look at what’s happening?’ But in the end they and Ronnie finished the album.”

Although the booklet that comes with the new Anno Domini 1989-1995 box set insists that Iommi put the Martin-fronted band “on hold” during Dio’s second spell, suggesting the guitarist believed it was destined to reconvene, he laughs at such a suggestion.

“With our band you can never say anything for sure. We broke up, came back together, threw somebody out and got them back in again,” he shrugs. “With Ozzy it happened two or three times, and twice with Ronnie. Black Sabbath band members are in and out like yo-yos. I’ve learned never to write off anything – unless somebody is dead.”

The resulting album, 1994’s Cross Purposes, recorded by Iommi, Butler, Martin, Geoff Nicholls and former Rainbow drummer Bobby Rondinelli, is undervalued in Sabbath’s sizeable canon. (Its closing track Evil Eye was co-written with Edward Van Halen, but goes uncredited as such due to publishing reasons.)

“I really liked Cross Purposes,” Iommi states. “Tony was singing great and the songs were very strong. I didn’t know [its co-producer] Leif Mases, but he did an excellent job.”

For a short period of time, Bill Ward returned to the line-up (Iommi doesn’t recall why Powell didn’t return).

“I had told Bill that we were going to South America and he reacted positively, so I asked if he’d like to do those gigs,” Iommi says, before saying with a laugh: “Bill asked: ‘Great, what shall I do? Meet you there?’ ‘No, Bill, you must come to England and rehearse the show.’ Bill lost track of things and we couldn’t do the songs from Headless Cross and Tyr, so we ended up doing a set of old Sabbath songs. That was a bit awkward.”

Although commercially Cross Purposes performed more than respectably, charting on both sides of the Atlantic (No.41 in the UK, No,122 in the US), Butler opted to return to Ozzy’s solo band. Iommi realised that some stability was necessary: “I said: that’s it – I’m getting Neil and Cozy back.”

The album Sabbath were about to make was assured of its notoriety when the band’s label I.R.S. put forward the name of Ernie Cunningham, better known as Ernie C, the guitar player with rapper Ice T’s group Body Count, as its producer. As realisation dawned that the album, which would be titled Forbidden, was becoming a car crash, Iommi was powerless to hit the brakes. Decades later, Ice-T’s spoken word part on the album’s track The Illusion Of Power remains a genuine WTF moment.

“Forbidden has been a thorn in my side for years,” Iommi sighs. “I knew all about Ice-T and that he was good, but I didn’t expect him to bring along his guitar player to produce the album. When a band knows its sound and exactly what it wants, bringing in an outsider is very disruptive. I found myself on the sidelines. Our whole situation had become so frail.”

To Iommi’s disbelief and dismay, Ernie C took Cozy Powell aside and asked him to play in an unfamiliar manner.

“Cozy is Cozy, you can’t have somebody telling him to do things differently,” Iommi remembers, aghast. “I know why Ice-T and Ernie were brought in. I mean Aerosmith and Run DMC had had their big hit [Walk This Way],” Martin muses. “But I wasn’t even certain I would be on the album, because Ice-T was coming in to ‘sing some stuff’. When I asked whether that was one or two tracks, or more, nobody knew. But the work done by Tony has brought the album right up to date. It sounds really Sabbath-y now.”

“I found some bits of guitar that Ernie hadn’t used [on the original album],” Iommi explains. “Within the obvious constraints, I managed to make things sound a hell of a lot better.”

Despite peaking at No.71 in Britain, Forbidden dropped off a cliff in the US and remains the least successful Black Sabbath album of them all.

For a musician, going out on the road, playing songs from it for fans and talking to journalists about an album that they don’t believe in is about as bad as it gets, and when reminded, Iommi grimaces.

“Forbidden caused a lot of turmoil within the band, but we’re professional,” he asserts. “But also, at the time we probably didn’t see the album quite as we do now. You know, there’s some good stuff on Forbidden. I wouldn’t slate it.”

Tony Martin recalls asking several times whether Sabbath’s original line-up would be getting back together. Despite assurances to the contrary, that’s what happened.

“Like I said earlier, I never write anything off,” Iommi states stoically. “When these things happen, they bring problems. Getting back with Ozzy brought problems. You’ve just got solve them.”

“The second time around, I saw the writing on the wall, and I understood it,” Martin says. “Black Sabbath is a major band. You’ve just got to fit in with that and take the rough with the smooth.”

After Forbidden, it would be almost two decades of good times and bad, with yet more reunions and sackings, before three of Sabbath’s founder members got together with producer Rick Rubin to make 13, the album that now seems set to be their epitaph (Bill Ward was unfortunately not on it due a contractual dispute).

Again without Ward, the band’s final gig was, fittingly, in their home city of Birmingham, on February 4, 2017.

Iommi and Martin are thrilled to propel the Sabbath records from the time Martin was with the band, for so long overlooked and neglected, back out into the public glare. It’s all so long ago that neither of them owns a complete set.

“Sabbath’s Tony Martin era has been pushed right into the background. A lot of people didn’t even know there were albums with him,” Iommi marvels. “I was often asked whether they would come out again and a new generation of kids can listen to them now, hopefully. I’m also pleased for Tony, because he was messed around a lot [by us] over the years.”

“How nice to hear that from Tony,” Martin says, smiling. “It’s the first time I’ve had validation of that era.”

So, given Sabbath’s treatment of him, why did Martin remain so loyal?

“In the beginning, I was essentially a nobody off the street,” he says modestly. “It must have been hard work dragging your younger brother around as he learns the ropes. It [getting sacked twice] didn’t feel great, but I don’t harbour any bad feeling.”

Is there a scenario in which the two Tonys could work together again?

“I’d be up for that, and I’m here if Tony needs me,” Martin offers. “But I don’t realistically think there’s any chance of it.”

“Like I keep on saying, I never write anything off,” Iommi says, grinning. “I’m doing my own album at the minute, and I played on two songs for Ozzy [for his most recent solo album Patient Number 9], but I never know what’s next. I enjoyed working with the Black Sabbath Ballet [in Birmingham]. I’ve done some other things that aren’t out yet so I can’t mention them. Obviously I won’t be touring the world for eighteen months again. I’m just happy being where I am. My life is never boring.”