Michael Thompson has tracked guitars for some of the biggest hits in popular music, recording sessions with Michael Jackson, Celine Dion, Toni Braxton, and Michael Bolton, working with R&B kingpin Babyface and Canadian über-producer David Foster in the process.

But in a new interview, in which the session ace breaks down his biggest hits, talking tone, gear and his approach to studio collaboration, he admits that working with Mutt Lange was the ultimate experience, a “personal dream” come true – and shared some insight into what makes the South African producer one of the biggest legends in the game.

Thompson was speaking to Mason Marangella of Vertex Effects, and just like his conversations with Dann Huff, Dean Parks and Eddie Martinez, it is another must-watch interview on the Vertex YouTube channel that shines a light on the often unsung heroes of the studio game.

Marangella’s conversations with session players yield an abundance of insight, and some incredible stories. Thompson is no different. Of course, Thompson has some renown as a band leader. The Michael Thompson Band returned to the studio last year with original vocalist Moon Calhoun back in the lineup for their first studio album in four years, The Love Goes On. But it was in the studio as a hired gun where he made his bones.

Working with Michael Bolton on a cover of Percy Sledge’s When A Man Loves A Woman was one that put Thompson on the map. Or rather, it put Thompson in the Rolodex of producers who needed an ace guitarist and quickly. It was huge. It still is. Not that Thompson had any expectations.

“It sure felt great and sounded great,” he says. “A couple of these tunes, I walked in and heard it and said, ‘There’s no way this isn’t a hit.’ But it felt good but who know? He wasn’t planning on it being the first single.”

“I never underestimate radio,” was Bolton’s take on it.

A conversation like this also calls into sharp relief just how much has changed in the music industry – not just the gear, but the budgets. Working with Michael Jackson? There were four or five studios in New York working all hours on HIStory. Money was no object.

Michael Jackson was super fascinated with the E-Bow. I was saying, ‘It’s like a magnet thing.’ And I showed him how it worked, and he hung for about 20 minutes and then moved onto the next studio

“They flew all my stuff to New York,” says Thompson. “I stayed at The Four Seasons. It was great.”

The day he met Michael Jackson was one to remember. He was already there and working under the auspices of David Foster by the time the King of Pop arrived.

We were at Sony Studios, and Michael wasn’t there for the first hour and a half or something,” he says. “We were trying parts… I was just doing the EBow, that actually never got heard on the intro but David wanted to try it.”

Barely a light was on in the studio. They worked under the cover of darkness. That was just how Michael Jackson liked it. Thompson was toying away with the Ebow.

“I look up and he’s sitting there right next to me, right close to me!” he recalls. “I was looking down and I was doing this and stuff, and he came in as I was doing it. He came in and he was real nice.”

And by that point in his career Jackson would have sold millions upon millions of records, but even for pop’s biggest selling artist, there’s always something new to discover in the studio. For Jackson, that was the Ebow, the hand-held super-sustaining electronic bow that can create woodwind, string sounds, whale song and more on guitar.

“He was super fascinated with the E-Bow,” says Thompson. “I was saying, ‘It’s like a magnet thing.’ And I showed him how it worked, and he hung for about 20 minutes and then moved onto the next studio and that was our little hang.”

After tracking Earth Song, Thompson was hired for They Don’t Care About Us, a track that features a bona-fide hall-of-famer as far as pop riffs go – plus a work of stunt guitar that blurs the line of what’s possible on the instrument.

Doubled by synthesizer wizard Michael Boddicker, it was known as the ‘the speed-racer section’ and was recorded at half-speed. It’s over and done in a matter of seconds on the track but took hours in the studio.

“When I hear it now, even at half speed, how did I do it? It was really muted, and there’s a synth doubling it,” says Thompson. “At the session, it took six hours to do this one thing… It comes and goes and people don’t realise the work that it takes to do a little section like that.”

But the session that takes the cake for Thompson was recording Shania Twain’s fourth studio album, Up!, when she was then married to Lange. Finally, Thompson would become a select band of session guitarists to work with Mutt Lange. He admits that, for a time, he did not think he would ever get the chance. When the moment arrived it did not disappoint.

“As a session player, he wasn’t just another producer whom you might happen to work with,” says Thompson. But lo, one day he came home and his answering machine was flashing. There was a message.

As Thompson remembers it, it went something like this: “‘Hi, Michael, this is Mutt, Mutt Lange, I wonder if you’d be interested in working with me on my wife’s album?’”

There was more.

“Then he said, in the same message, ‘Of course, I’ve been aware of you for some time.’ How is this guy aware of me!?” says Thompson. “It was like you couldn’t have bought a better rock ’n’ roll fantasy dream.”

Reality, however, is complicated. Thompson was in Switzerland, tracking with the Italian guitarist and actor/director Adriano Celentano (Celentano is a massive star in Italy, has a cameo in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and starred in Sergio Corbucci crime-comedy The Con Artists).

That was okay, Lange and co would come to him. They’d take the train, the music with them, and when they got there, in a rented studio, Thompson got acquainted with a set of tracks that were nearly finished. There were guitar tracks all over it but Lange wanted more. That’s where Thompson came in. He was going to be what Lange refers to as “the grease guy”.

“I came in and there were all these guitars on the tracks, electric guitars, and I always had suspected that [Lange] played on his stuff but he never credited himself,” says Thompson. “He credits himself on background vocals but not guitars. So there were all these [parts]. Every tune had these meat-and-potatoes basic parts.

“I remember he had this Boss – because I had the same box – that had all their amp models and their pedals in the one space, and he had done everything with that. And he had one guitar… You’d expect that he had all these guitars and amps, and all this stuff, but no.”

What Lange did have was an ear, and that you can’t buy. If you have waited a lifetime to work with the best producer in the business then you are waiting for that moment when for the genius to reveal itself.

It duly did. Not least in Lange’s temperament as they worked from 11am to 3am. “It never was a drag,” says Thompson. “He is such a nice, gentlemanly guy.” But also in his ability to pick out details in a take and pull them together to make the ultimate take. This blew Thompson’s mind.

“He would put Pro Tools in loop record, and we had figured out a verse part, and I would just play,” says Thompson. “It would keep looping and recording, and he would remember that 11 times back he heard a good shhbrang! Or 14 times back he had a good chukka. So he would sit there and make this comp of the killer pass, and then he would take other stuff you did and make a double of it.”

Given what Def Leppard’s Phil Collen has said about Lange before, it begs the question why he didn’t just play the parts on it before. Thompson wondered that himself, but just as Dann Huff had told him, Lange preferred to bring a pinch-hitter onboard. He knew that the tracks needed something else, a six-string specialist.

“I said to him, ‘Why don’t you just do all the guitars?’ He said, ‘I ain’t got the grease like you, mate!’ I saw that’s what he wants, that upfront guitar that’s got the grease,” says Thompson. “Prior to me doing that album, Dann had been the guy.”

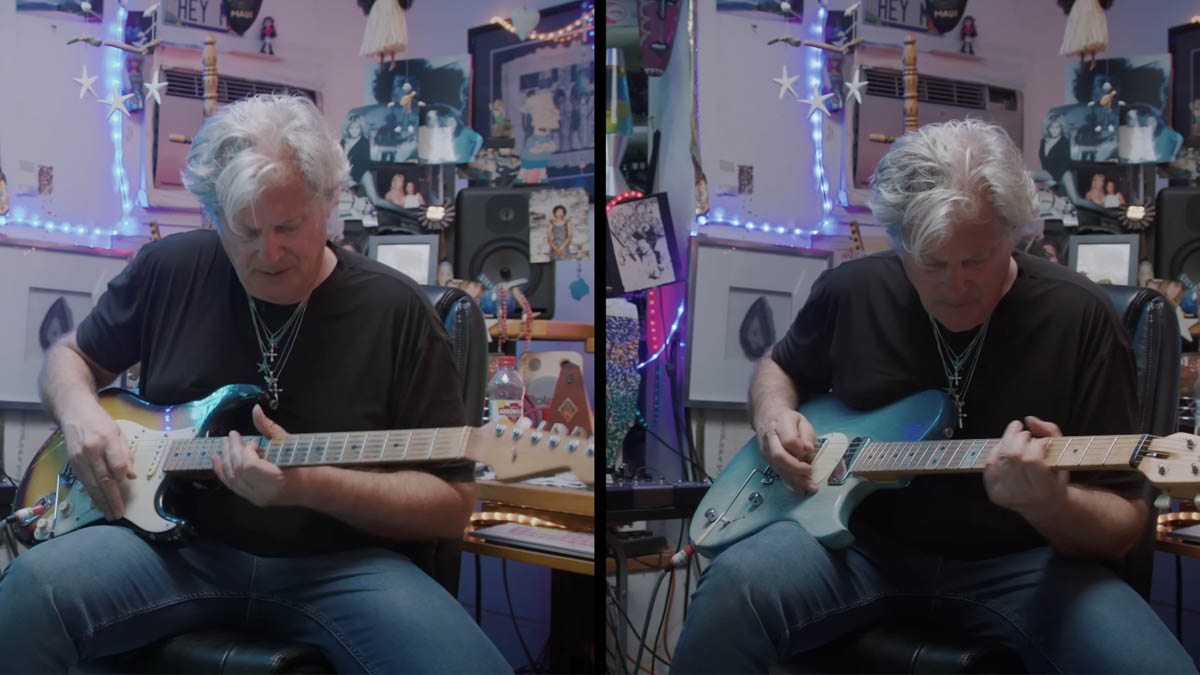

With that, it was time for Thompson to play Up! for Marangella, on the Rickenbacker 12-string guitar that he used on the session. Check out the video above, and be sure to subscribe to the Vertex Effects YouTube channel because these conversations are gold, bringing new perspectives to songs that have become part of the very fabric of popular culture.