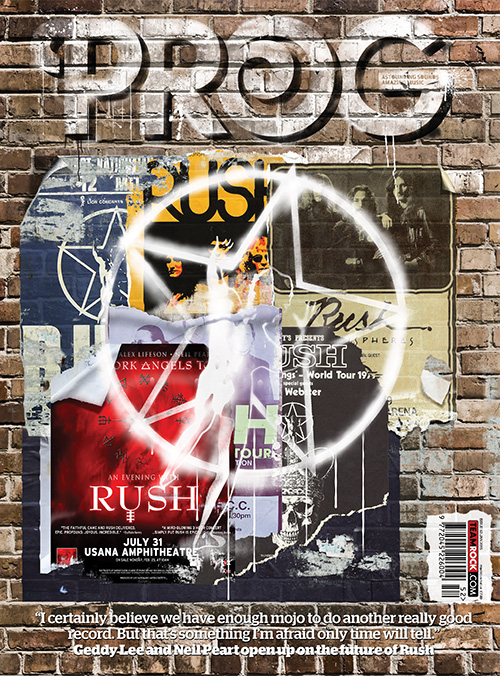

In 2015 – before Rush announced what would be their last-ever tour – the late Neil Peart gave Prog one of his most personal and revealing interviews ever, discussing himself, his passions and his thoughts on the band’s future.

The low clouds and mist have only just burned off as the Los Angeles sun struggles to assert itself along the Santa Monica coastline. The air still smells like rain and Neil Peart is just back inside from admiring the garden. The house is still quiet – like most days, he’s the first to rise – and as we talk the intercom occasionally buzzes into life to check which part of the house he’s in. His office, as it turns out.

Neil’s on the author trail. His new book, Far And Near: On Days Like These – a companion volume to 2011’s well-received travelogue memoir, Far And Away: A Prize Every Time – is on the stands. There’s also the matter of the day job as drummer and lyricist in Rush – stories and reflections from their Time Machine and Clockwork Angels tours make up the bulk of the book – and life as a dad the second time around.

For someone so infamously guarded (he did write the lyrics to Limelight, after all) he’s surprisingly open about his daughter, five-year-old Olivia, and the life he lives now in California. Constantly restless and consumed by wanderlust he may be – but Neil Peart sounds like a man who’s found home.

This latest book seems more reflective than the first volume.

I suppose it’s all about me as an audience. More and more I realise that’s my presence in the world; I like to observe, especially in a moving vehicle. On the motorcycle, the world comes towards you like a show, and I’m very tuned into that.

A writing exercise I always do is, whatever I’m looking at, I think, “How would I put this in words?” A lot of Ghost Rider was written directly to a friend of mine who happened to be temporarily incarcerated at the time, so I was always looking at the world around me and discussing my feelings with myself in terms of a letter to him.

That’s very much the character of the book; I describe the writing as being a series of different letters to someone.

The new book reflects Ghost Rider in tone: it’s a very honest, almost exposed read in some parts.

I do try and talk about my grief and what happened to me in the book, because it helps people. Ghost Rider is by far my most widely-read book; that kind of puzzles me, because the others are an awful lot happier to read.

But there are certain people who have endured the same kind of experiences and loss as I have, and found it helpful, so I do make the effort to share. I try to share those things to try and help people know they’re not alone, because it helped me to know that I wasn’t alone then.

You first started cycling while on tour in Utah in the mid-80s. What spurred that decision?

That was just a day off on tour and I thought, ”What can I do? I know, I’ll get a bicycle!” And that was the beginning of the two-wheeled world for me.

Most people would have just gone to the bar.

I can divide my touring life into two phases. I realised on the very first tour in 1974 that this was no kind of life, and there was so much hanging-out time and it was potentially so self-destructive. And I started reading then; I filled all the empty hours with the education that I missed, delving into all the genres.

I could reach national parks, the desert, the mountains, even the prairies. The world I experience on the motorcycle is the real world

There was the book period; and then in my 30s I got into bicycling and then into motorcycling, and they became the escape from touring and the injection of life, freedom, engagement with the world – and it’s still something that I love.

Do you remember making the transition from bicycle to motorbike; was it very clearly defined?

I was always afraid of motorbikes! I always said that when I grow up, I’d get a motorcycle and it’d be a BMW; and it wasn’t until my mid-40s that I decided I was as grown up as I was going to be. I started riding and then I started to realise that this would be a nice way to tour because bicycling had been great. On a show day I’d be jittery as I had to perform, so I’d ride my bicycle around the city and go check out the local art museum. I had an outing and got an education along the way; so motorcycling was just a way to take that up a notch.

Instead of art, I could reach national parks and get out in the desert and the mountains, even the prairies. The world that I experience on the motorcycle is the real world. Between shows, I averaged it out, I travel about 500 miles riding – and none of it is freeways or motorways.

Motorcycles, cars, an incredible Aston Martin like James Bond used to drive…

I showed people pictures of that and they say to “Oh, that’s my dream car,” and I say, “It’s mine, too!” I’m far from jaded about any of that, and of course I appreciate it totally. I spend a lot of time around my cars and I’ve been doing a lot of racing this year in a series called the 24 Hours of LeMons. The cars have to be worth no more than $500 – essentially it’s a junker and you go endurance racing. Our racing team’s called Bangers and Mash!

You’ve become quite the accomplished travel writer now.

I’ve been interested in prose writing since the 70s. I went to a shop in Little Rock and bought a typewriter and set out to write. I tried a novel, I tried a screenplay, I tried everything; and then in the early 80s, I did a bicycle trip to China and I consciously decided not to take a camera with me but to try and capture the journey in words.

I came back and made that up into my very first travel journal. I realised that it was what I wanted to pursue and so it was fortunate. I worked on writing for 20 years before anyone saw it, which was so lucky; I wish I’d had the same luxury with music.

It was a good decision to go on without an opening act, but I miss that part of it: I miss the socialising

You and Kevin J Anderson collaborated on the Clockwork Angels novel. Was that a gratifying experience or so much toil or both?

Working on the novel was fantastic for me. We’ve just finished the graphic novel of it too, with a comic book publisher called Boom! Kevin and I didn’t want to leave that universe and he suggested we carry on with a lot of the lesser characters from the novel and flesh out their stories. The next one will be called Clockwork Lives. I’m not done with that project. I think it could be an opera in the classic sense; that would be fantastic.

You write constantly, lyrics too: tell us about your ‘scrap yard.’

I collect bits all the time; if I have a nice line that I like, or a possible title then I note that down. Going back over your notes, I call it fishing in the scrap yard: that line goes with that and that could go over there; so much of our stuff has happened like that… I know that the Roll The Bones title had been in my scrap yard for a decade or more.

Your lyrics sound almost fantastical at times, but the reality is that you focus on very universal themes: you write about the everyman much more than you’re given credit for.

I try to find that particular kernel in things, to find the universal. The other day I was thinking about our song Distant Early Warning, which is from… 83? And I was watching what my friends were going through at the time, work difficulties and marriage difficulties; and what the world was going through at the time when the Soviets had just shot down that airliner.

All of that stuff was out there and I wanted it in that song; and the little twist in that, the lyric: ‘you sometimes drive me crazy, but I worry about you’ – that is life, you know? That’s one of the few times, out of all the songs that we’ve written; there are only a handful of lines that I could really replicate, you know, endlessly, and that’s certainly one of them.

Another one is that line from Presto, ‘what a fool I used to be’, because it’s always true. “Oh, yesterday I was a fool – but not today!” That’s a song I would like to play live again; I hope we can someday. I love how we revitalised that song by performing it in front of an audience.

There’s another one called Hand Over Fist, which has the same personal and universal elements to it that I would really love to revive. We’ve always said that if we could remake one album, an album that could have been so much better, where the songs are so much better than the record is, then Presto would probably be the one we would pick.

Two Rush tours feature heavily in the book – Time Machine and Clockwork Angels – were they very different tours?

Undoubtedly so; a different character even. Clockwork Angels was just so satisfying on so many levels – the music we were presenting and the way we felt we were playing as a band, the way it was happening, having the string players. Socially, I think people can forget the day-to-day of our lives. These new people came into our world, and every day, soundcheck would end with us going back to talk to them for a while. So that was a very fresh shot of novelty and enjoyment for us and entertainment, just the hanging out.

We did feel that with Clockwork Angels live we reached a prime that we’re all very proud of and pleased with

So you still miss touring with other people?

We used to have that with opening acts, you know? Someone sent me a picture of us with UFO the other day; we got very tight with them when they opened for us, musically and personally – it was really a treat. It was a good decision we needed to make to go on our own without an opening act, but I miss that part of it: I miss the socialising.

There are still no Rush dates confirmed yet – Alex suggested there might be, Ged wasn’t so sure – but where do you stand on touring now? Does the idea of it still enthral you, or leave you cold?

It’s a true dilemma; there’s no right answer. People say to me, “Are you still excited when you go out on tour?” Should I be excited about leaving my family? No, and no one should. It’s as simple as that: if you put aside the fantasy of it, it is what it is and has to be done, and that’s fine; and I pour my entire energy and enthusiasm into it. But, of course, I’m of two minds about the whole idea.

Your write very lovingly about your daughter Olivia in the book: how old is she now?

She’s five. And again with the separation – it’s heartbreak. I’ve been doing this for 40 years, I know how to compartmentalise, and I can stand missing her, but I can’t stand her missing me. It’s painful and impossible to understand for her. How can a small child process that? And there’s the guilt that comes with that. You feel guilty about it, of course. I’m causing pain.

But part of you still yearns to perform?

Me, Ged and Alex all met about a month ago now. Playing was the activity that we all most wanted to do, though we’ve made no real decisions yet. We’re all in our 60s, and we did feel that with Clockwork Angels live we reached a prime that we’re all very proud of and pleased with.

But that is the hardest thing by far: performing. You can fiddle around in the studio until your dotage, but as far as going out there and playing – especially drumming – for me is such an athletic undertaking. We really want to utilise that while we still have it.