The date: January 3, 1976. The place: Olympia, West London, venue for The Great British Music Festival. Bad Company are headlining in the vast, old Royal Agricultural Hall. Promoter Mel Bush isn’t best pleased. He’d hoped to sell out the 6,000-capacity glass and steel-roofed shed but huddled in his Afghan coat, this writer reckons the house is no more than a third full. The Great Blow of January 2 has cut the capital off from the shires and Home Counties. Many of Bad Company’s heartland audience can’t get here.

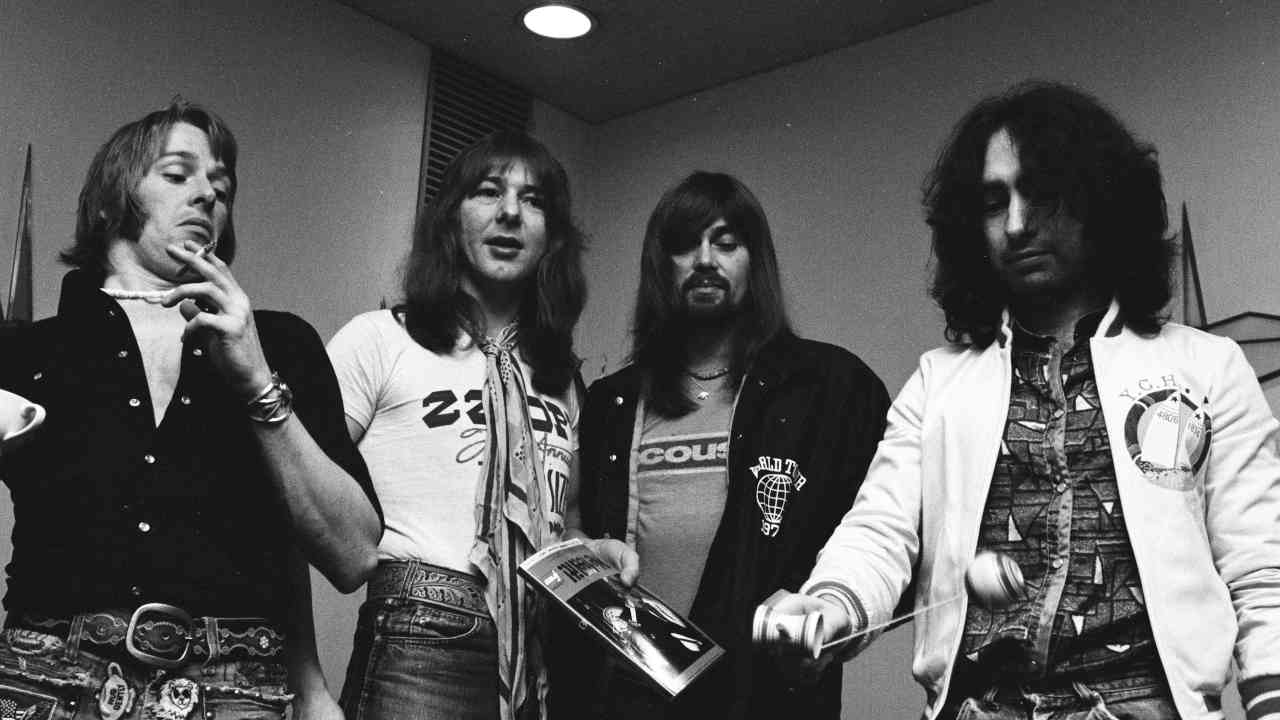

Around 9.30pm, Paul Rodgers, Mick Ralphs, Simon Kirke and Boz Burrell stroll on stage after a prolonged slow handclap. The audience, most here since the doors opened at midday, are draped around the vertiginous seating areas or the cold, concrete floor. They’ve come down with a bump after seeing Nazareth depart an hour earlier. Ronnie Lane’s Slim Chance, The Pretty Things, Be-Bop Deluxe and Charlie are a fading memory. Olympia is cold and the Watney’s Red Barrel is warm. And now it’s running out.

But then the PA, provided by Elton John and Deep Purple, crackles into life and Ralphs’ Les Paul ’59 Sunburst cranks the juice out of his two 100-watt heads and bleeds white noise from his 4x12 cabs. It’s fucking loud, or as Ralphs would say, “So fucking loud it will shred the hair off your head.”

When Kirke kicks his bass drum into life, the zonked-out tribe staggers to its collective feet. Whooargh! Burrell runs a tricky scale and leans into Rodgers, who laughs and says, “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Sorry we’re so fuckin’ late but we’re Bad Company and we hope you are too.”

Wallop. Straight into Deal With The Preacher and the rock drug and the funny Players Number 6 do the business.

Three weeks later, Bad Company release their third album, Run With The Pack. The seventh release on Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song Records, it proves to be a spare 36-minute marvel, and if it doesn’t have any cock-rock strutting hits as such – no Can’t Get Enough – it does contain a more subtle blend of Bad Company’s formula of white-boy funk mixed with transatlantic country blues, some highly strung ballads and a solid serving of British R&B.

Pack, as the group will call it, is recorded in autumn 1975 using the Rolling Stones’ Mobile Studio, tethered to a small studio within a modest château in the perfumed hills of Grasse, Provence, the latter-day inspiration for Patrick Süskind’s olfactory novel Perfume. The 10 tracks on Run With The Pack have a decent bouquet too and will prove with the benefit of hindsight to be a mid-point mission statement for the 1970s. It’s the last call for the old-school boys before punk rock arrives, threatening to kick everyone’s head in – even though Rodgers and Kirke are actually in their mid-20s, not much older than Joe Strummer, who will soon form The Clash. Indeed, Strummer is in the crowd at Olympia with Mick Jones in tow, headbanging like the best of ’em.

Perhaps the difference is that Bad Company are now major rock stars, in America at least. Britain? Not so much. That’s because we’re taking them for granted. They belong to us and not the Yanks. We know where they came from: Free, Mott The Hoople and King Crimson. They’re ours, mate. We’ve got the records, been to the gigs and bought the T-shirts.

What we don’t know is that Mick, Paul, Simon and Boz are now tax exiles on the advice of manager Peter Grant, who sends them to live in Miami in 1975 while they undertake a punishing US tour, and then registers the band to an offshore address in Saint Helier, Jersey, in the Channel Islands, to avoid income tax and corporation tax. In Britain in 1975, the basic rate tax is 35 per cent, but once you earn over £20,000, and Bad Company do, that rises to 83 per cent. The rats are leaving the sinking ship. Zeppelin will become nomads. The music press will document the fact that our rock stars turn their backs on Britain. The void is tailor made for punk’s arrival.

Speaking to Classic Rock in 2013, Paul Rodgers recalled: “We were doing something called a tax year at that time because we’d heard the government was going to take, I think it was 96p [not quite] in the pound of everything we earned. So it wasn’t just the brain drain. It was the rock’n’roll drain as well. We skedaddled the heck out of it. Punk happened underneath that. Honestly, I never liked it. I never understood it. And it made no difference to the way we played. Not for a second.”

Bad Company might have agonised a bit, however, when they issued the opening anthem on Run With The Pack, Ralphs’ belting Live For The Music. Featuring an infectious, rolling riff, this isn’t an apology – it’s a diversionary tactic. The next track is Simple Man, also penned by the guitarist: a tribute to some long-lost, horny-handed man o’toil, straight out of Ralphs’ Herefordshire memory bank. Simple Man sounds very Free-like too, a working-class blues that suggests Ralphs is saying, “Look, I know I’ve finally made it and I live in a mansion in Henley, but I haven’t forgotten my roots.”

Speaking to Classic Rock in 2013, Ralphs recalled: “We lived in Malibu when the tax was ridiculously high and everybody was leaving the UK. We decided to cushion the financial burden and ended up living in California for six months in a rented house. We picked Malibu because it was about 45 minutes from LA, to try and get away from the madness. But of course we didn’t – it just followed us out there.”

Kirke, the most self-contained of the band, would ride his Harley across America when the tour ended. He had plenty on his mind. “Suddenly the little clouds started looming,” he said in 2013. “We just didn’t have our family base. I still think Run With The Pack was a great album but I think after that, the pace started to get to us.”

Before it did, the four men collaborated on Honey Child, a full-band proposal that concerns the kind of ‘17-year-old nubile in a hotel room’ adoration that you wouldn’t get away with now. Luckily the, er, lady in question is soon 21 in the song, so no need to telephone, but this is the exact kind of song that will draw a line in the sand between those who come to rock and those who want to turn the snowstorm upside down and spit upon their elders. Put it this way: when Bad Company depart the UK in January 1976 to close the second leg of their US tour, Honey Child won’t cause a seditious ripple. But by the time they get back in the early summer of ’76, they will be astonished to survey the scene.

Rodgers’ Love Me Somebody is another, better reason why the Pack LP abides. A gorgeous slice of piano balladry with a Dobro-tinged feel and an organ bridge before a classic R&B breakdown, it has echoes of Steve Winwood. So right now the album sounds more in touch with its 1960s forebears than the future and that’s hammered home in the title track, which starts: ‘You never give me my money… you only give me your sympathy…’ It’s so cheerfully indebted to The Beatles’ Abbey Road song You Never Give Me Your Money that you have to remember that such a clunking lyrical name‑drop was somewhat unusual then – The Beatles had exhausted their goodwill by 1975 and wouldn’t get it back until John Lennon’s demise five years later.

Even so, this is a great song. Rodgers’ piano work is perfectly judged and Ralphs is his usual somewhat reticent self. Unusually controlled for a lead guitarist, he permits himself a brief, syrupy, Mott-like solo – “smooth and creamy” he calls it – while the string arrangement from Liverpudlian Jimmy Horowitz is bang on the money.

Rodgers composed Run With The Pack with a string arrangement in mind from the outset. “I wrote that song on the piano and when I played it to the guys they fell right in,” he said in 2013. “In my head, the strings were always a part of the song. Jimmy Horowitz came around to the studio session with a tape recorder in hand and while the track was playing, asked me how I wanted the strings in the background. I sang the part that I had been hearing in my head and he went off and wrote it up.”

It’s a natural choice for the album title. “I’ll never forget mixing the song with [engineer] Eddie Kramer,” states Ralphs. “We both had all hands on the desk and were riding about 36 faders, trying to do a mix all in one take and get all of the parts at the right intensity. In the end, we had to do it in two bits as it was just too much!”

Side two begins with the more reflective and instantly catchy Silver, Blue & Gold, Rodgers’ third straight offering and a potential hit single. Kirke said in 2013, “We weren’t particularly a singles band, and I think that was a hangover from Zeppelin. Peter [Grant] wasn’t too keen on singles. But Ahmet Ertegun, the head of Atlantic Records, called Peter, and I can remember Peter telling me, ‘Look, you’ve got to have Silver, Blue & Gold as a single.’

“Today, it’s one of our most requested songs. For various reasons, we don’t do it. I liked the harmonies and I thought it was a pleasant enough song, but blimey, it became almost as popular as Feel Like Makin’ Love. So what do I know?”

They opt for Honey Child instead, although the radio hit from the album, perhaps somewhat annoyingly, turns out to be their cover of Young Blood by Leiber, Stoller and Doc Pomus. The song was originally made famous by The Coasters, played by The Beatles at the Cavern, and nudged into the band’s purview by Leon Russell, who’d sung it at the 1971 Concert For Bangladesh with George Harrison, Ringo Starr and Eric Clapton as back-up.

This is the Company camping it up a bit, with the ‘look-a here’ and ‘what’s your name’ lines delivered in comic fashion, and Ralphs enjoying a return to his All The Way From Memphis accent. It’s a slight thing but it gets so much airplay in 1976 that its Top 20 status accounts for a large chunk of the album’s three million sales.

Do Right By Your Woman ensues, almost as if to say, ‘That’s enough mucking around.’ A classic Rodgers composition and the best thing on the album by miles, the song is a luscious country blues decorated with acoustic 12-string guitar and just the right amount of harmonica. Again one is struck by the band’s modest production – there’s barely an overdub to be heard.

The penultimate track, Ralphs’ Sweet Lil’ Sister, owes a further debt to The Beatles since it’s a barely disguised fusion of Get Back and Back In The USSR, with a distinctly Southern Rock pulse that must have impacted on the Black Crowes’ obsession with British rock circa this very era.

Ralphs wrote it in a hotel room as a way of expressing his frustration at road life and the need to find some physical contact. He was hit hardest by homesickness. The band drowned their sorrows or snorted them.

In 2013, the guitarist said, “The whole thing was all par for the course in those days, wasn’t it? The 70s was quite a decadent time. We were all having a good time, doing it all together, whatever we did. I think it probably didn’t help in the long run, though. It probably had a counterproductive effect because when we come to the fourth album [Burnin’ Sky], we found we hadn’t got any ideas. We were floundering, you know?”

Rodgers elaborated: “There was a lot of cocaine washing about in those days. It was the drug of choice at that time. I stopped doing any of that stuff [in 1976] and I began to feel isolated from the band actually.”

There are tons more sobs on the closer. Rodgers’ Fade Away (again decorated by Horowitz strings) combines phased production, Burrell’s prominent bass lines and some neat staccato piano playing. It’s the most futuristic track here, with the best lyric: ‘High adventure I’ve just begun/Fame and fortune got me on the run.’ Rodgers seems to be acknowledging the need for change while bemoaning the lot of the exile with money to burn and nowhere called home to spend it.

Hacking round Jersey was no solace to a Middlesbrough lad. “In Jersey there are two things you can do: there’s a cinema and a fish and chip shop. Oh, there was a nightclub as well. The first time we went to the nightclub, they’re like, ‘Hello boys. Oh, Bad Company? Yeah, come in. Take the front seat. Like a drink?’ The next night it was like, ‘Oh, it’s you guys again.’ Third night it was like, ‘Oh, you’re back?’ Fourth night it became, ‘What do you want then?’”

On the inside cover of the album’s gatefold sleeve, the four members of Bad Company are photographed by David Alexander perched about a sofa in Swan Song’s games room. There’s a table full of beer in front of them and a Bugs Bunny cartoon plays on the TV. None of them is smiling. Each one looks separate and moody, suggesting: ‘We’re serious rock stars but we don’t have to be happy about it.’

The front cover is a shiny, silver thing by artistic designer John Kosh, who has serious credentials working for The Beatles, the Stones, The Who and T.Rex (he creatively designed Abbey Road, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out! and Who’s Next). He interprets the Pack image with an alpha male wolf standing guard over an alpha female wolf, as four cubs – quite possibly our heroes – suckle her teats (milking the music industry?).

One person who likes that dissolute vibe is Don Henley and, as a direct result, he will hire Englishmen Alexander and Kosh to create the sleeve for the next Eagles album, Hotel California.

Run With The Pack may not be Bad Company’s flashiest, but it’s their defining moment. The title track is released as a single on March 19, 1976. On that night, the group play Dallas Memorial Auditorium with Ted Nugent in support. Also that night, former Free guitarist Paul Kossoff will die from a drug-induced heart attack on a plane flight from Los Angeles to New York City. Kossoff’s band Back Street Crawler had been scheduled to play a UK tour with his old Free mates. Bad Company promptly pull their concerts for two weeks, but will return in triumph at Madison Square Garden.

Looking back in 2013, Ralphs expressed some regret at the way the band were perceived in England. “We were just trying to play what felt good and natural. I think that is what gave us our identity. We always tried to be natural. We would play soul and blues favourites at rehearsals, instead of learning new songs.

“My favourite guitarist,” he continues, “the man who inspired me to play, was Steve Cropper. I guess we wanted to be the MG’s with Otis Redding. Basically, we played like a bar band, but soon it was clear that the bars were getting very large indeed!”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Bad Company