“You get lucky sometimes,” Keith Richards says of Gimme Shelter, the greatest song he ever wrote. "It was a shitty day. I had nothing better to do."

The tone is lightweight, almost laughable. Yet the song was wrought from the heaviest of materials. The Rolling Stones were still trying to climb out of the career-grave that their critically derided 1967 album Their Satanic Majesties Request had left them in, their plans persistently thwarted by the rapidly disintegrating physical and emotional state of their other founder-member guitarist, Brian Jones.

Their 1968 follow-up, Beggars Banquet, recorded largely with just Keith on guitar, had been a classic, but their final hit with Jones, Jumpin’ Jack Flash, had been their only chart single in the UK for 18 months. Now with Keith’s old lady – Anita Pallenberg, stolen from Jones the year before – filming sex scenes with Mick Jagger for his movie debut in Performance, Keith’s mind was all doom and gloom as he sat snorting coke and heroin at gallery owner Robert Fraser’s Mayfair apartment one stormy day that autumn.

Lounging with his guitar in a room decorated with Tibetan skulls, tantric art and Moroccan tapestries, chain-smoking and depressed at the thought of Anita being with Mick, Keith began to strum as lightning flashed across the London sky.

“It was just a terrible fucking day,” he recalls in his memoir, Life, “this incredible storm over London. So I got into that mode – looking at all these people… running like hell.”

Leaning on the same open chords that had become his signature, he crooned, ‘Oh, a storm is threatening, my very life today.’ Sounded good. He continued to strum, added another line: ‘If I don’t get some shelter, oh yeah, I’m gonna fade away…’

Six months later, when the Stones reconvened to begin work on their next album, Let It Bleed, the song of ultimate doom Keith had begun that stormy day, now titled Gimme Shelter, was among the first he and Jagger began working on with producer Jimmy Miller.

There were other monumental moments on the album to come, not least Jagger’s You Can’t Always Get What You Want. But everything the Stones would become, everything they would be glorified as – the greatest, most legendary, most daring and sophisticated and dark and evil and sexy and cool rock’n’roll band in the world – would be summed up by the apocalyptic Gimme Shelter, the album’s opening track.

It would be another six months, though, before they’d finished with it. In the meantime the Stones went through the most turbulent period – artistically, personally, commercially – of their career.

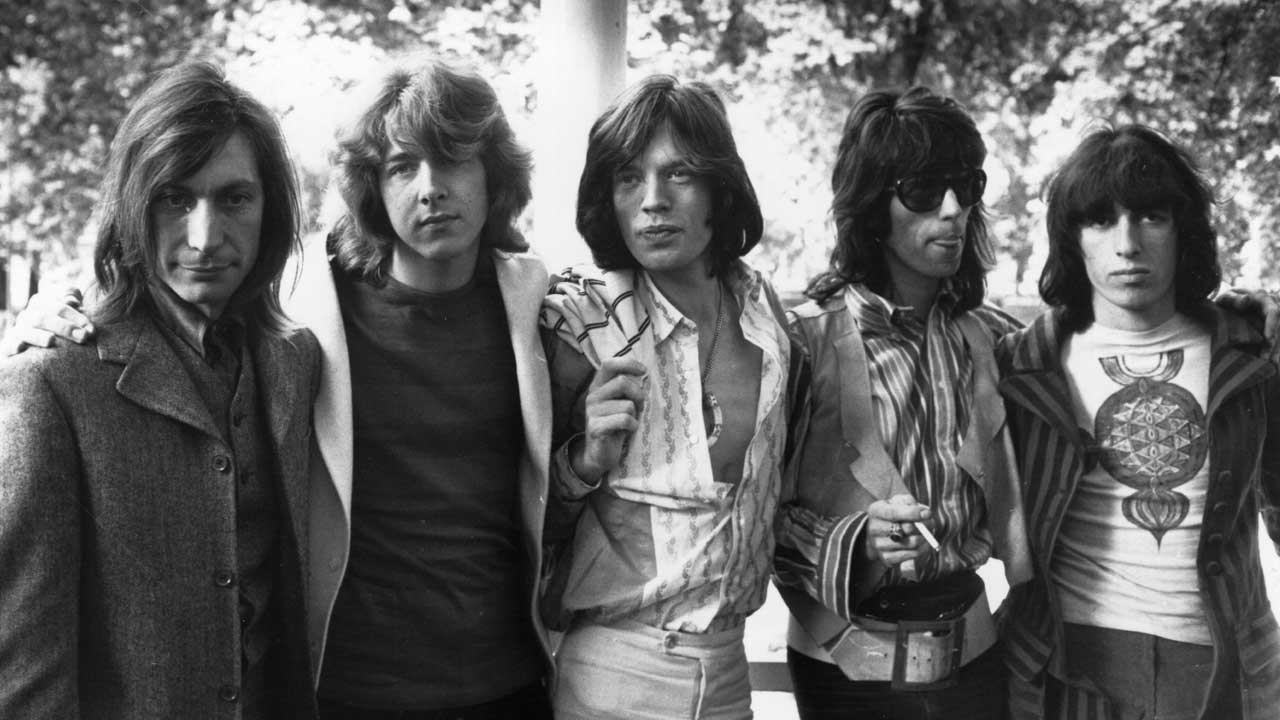

After Jones, who had officially been ousted from the group in June ’69, was found dead in his swimming pool just three weeks later, the Stones went ahead with their planned free concert in Hyde Park, with new guitarist Mick Taylor.

They also announced their first US tour for three years, due to start in November. First though, they had to complete the album. Miller argued there was something missing from Gimme Shelter, something that would turn good into great.

They found what they were looking for in 20-year-old Merry Clayton. Suggested by producer and long-time Stones acolyte Jack Nitzsche, Clayton had made her name through duets and backing vocals for Ray Charles, Burt Bacharach and Elvis Presley, among many others.

She laughingly recalls how she was about to go to bed when she got Nitzsche’s call: “It was almost midnight. I was pregnant at the time and I thought, there’s no way in the world I’m getting out of bed to go down to some studio in the middle of the night.”

But her husband, jazz saxophonist Curtis Amy, talked her into it.

“I’m wearing these beautiful pink pyjamas, my hair was up in rollers. But I took this Chanel scarf, wrapped it round the rollers so it looked really cute, went to the bathroom and put on a little lip blush – ’cos there’s no way I’m going to the studio other than beautiful!” Throwing a fur coat around her shoulders, she turned up at the studio “ready to work”. She admits to being somewhat nonplussed when she read the lyrics Jagger handed to her.

“I’m like, ‘Rape, murder…’? You sure that’s what you want me to sing, honey? He’s just laughing. Him and Keith.”

They began the session, and the effect was instant. “You listen to the original tape you can hear Mick whooping and hollering in the background,” Merry says.

Of course, there would be a grim postscript to the story of Gimme Shelter. While it became the most praised album-only track in the Stones canon – “The cleverest amalgam of powerful sounds the Stones have yet created,” reckoned International Times; “Ecstatic, ironic, all-powerful, an erotic exorcism for a doomed decade,” claimed Newsweek – it also became the emblem of the moment when the 60s dream flared into the 70s nightmare.

Released on the same day in December 1969 as the Stones’ ill-starred, bad-acid-and-cheap-wine appearance at Altamont Speedway in northern California, at which teenager Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death by Hells Angels, Gimme Shelter would also become the all-too appropriate title of the Maysles brothers’ documentary film of that debacle: the moment when the Stones’ music seemed to become a mythic force unto itself. Or as Albert Goldman put it: “An obsessively lovely specimen of tribal rock… rainmaking music [repeating] over an endless drone until it has soaked its way through your soul.”