Born from punk but geared by avant guile, Swindon’s XTC were always different to the ‘learn three chords and now play’ pack. In thrall to Be Bop Deluxe, Captain Beefheart and Todd Rundgren, among others, their innovation became the blueprint for upcoming angular pop boffins. In 2012 Prog asked the question: how prog were XTC?

“If you categorise prog as long songs with extended soloing, then XTC isn’t that,” says Knifeworld mastermind Kavus Torabi. “But if you regard prog as extremely inventive music with extremely high-level musicianship, a constant search for perfection, then XTC are totally prog. They were always reinventing themselves but in a completely natural way. They really tick all the boxes!”

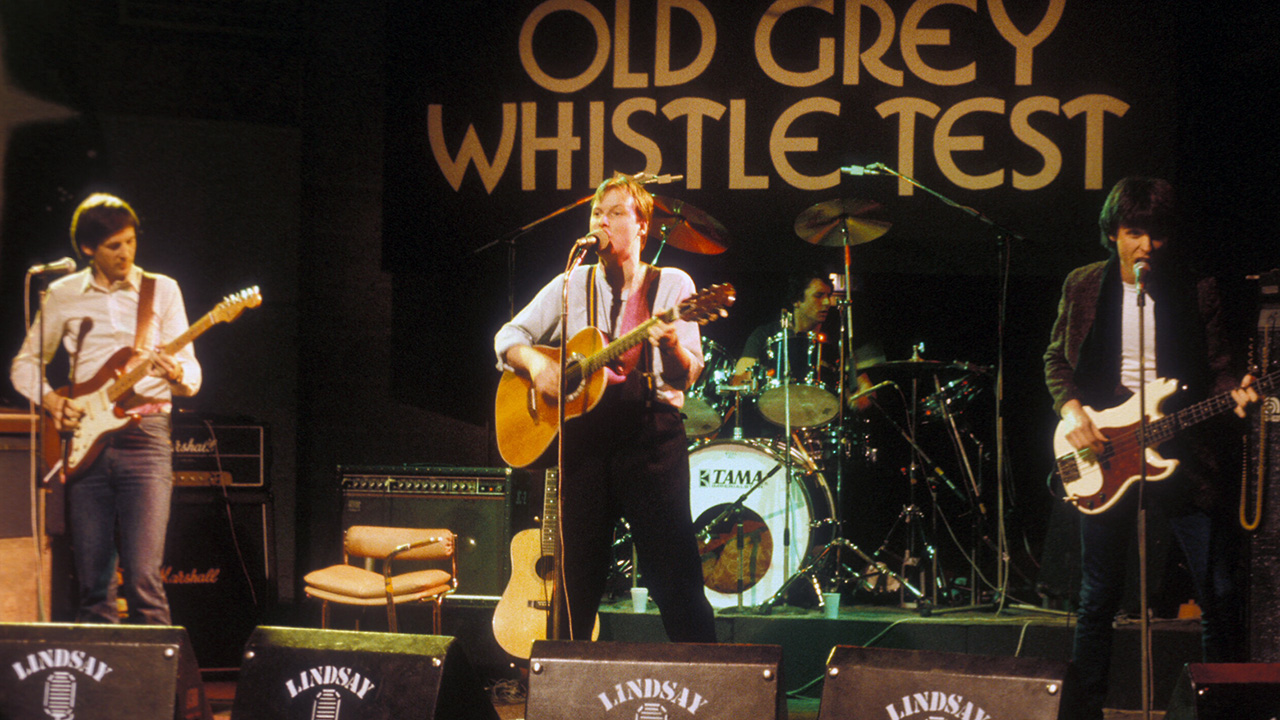

Emerging from the outer fringes of the punk rock and so-called new wave scene that purported to be lighting a fire under the complacent arse of early 70s prog and arena rock, Swindon’s XTC earned the patronage of John Peel and became one of the most critically lauded bands of the era by deftly side-stepping every imaginable cliché and swiftly establishing themselves as perennial square pegs.

Early singles like Science Friction and This Is Pop? seemed to ally the band with their punk peers to a degree; but even on their debut album, 1978’s White Music, they were displaying the kind of feverish invention that owed far more to prog’s experimental instincts than anything the three-chord generation could conjure up through a fug of spittle and safety pins.

“Punk opened the door to the amateur and I loved the energy of it,” admits Andy Partridge, XTC’s de facto leader and frontman. “But we got a lot of stick around that time. People would say, ‘Oh this lot are too smart-arsed! They’re too clever and quirky!’ We were just playing what we wanted to play. ‘If our playing’s better than yours then maybe you should hurry up and get better! Don’t blame us for being ahead of you in the race,’ you know?

“I remember I got up at some jam session that Virgin organised. The guy drumming was from X Ray Spex and he could barely hold a rhythm down. He was hating the fact that I could play half-decent! There was a lot of inverted snobbery back then.”

Signed to Virgin while punk reached its peak as a media sensation – the proudly prog-orientated Harvest imprint being the other label showing interest, according to Partridge – XTC were never a band content to stick to a formula or fall into line with the musical status quo. Whether crudely dismantling Bob Dylan’s All Along The Watchtower on White Music, or drifting into hypnotic art rock on Battery Brides and Life Is Good In The Greenhouse – both from 1978’s Go 2 – Partridge and fellow songwriter Colin Moulding were very audibly in love with the possibilities of composition and recorded sound.

If their short hair and skinny jeans suggested they were joining in the widespread denunciation of prog’s great and good, it was merely an aesthetic necessity. In truth, XTC were bringing two worlds together with considerable skill. “Early on, we were often described as prunk...or was it pronk?” chuckles Partridge. “In fact, I really liked a lot of classic prog bands. I loved Yes, but for me every eight minute Yes song could’ve been four two-minute singles! I liked the conciseness of getting it all done in two and a half minutes.

“If I’m being honest, the 1976 XTC was basically me being in thrall to what Be Bop Deluxe were doing – short pop songs but with enough musicality and pushing of the envelope to make it interesting. And that’s ironic, because after we made White Music and Go 2, Bill Nelson suddenly did his Red Noise project and everyone said, ‘He’s ripping off XTC!’”

That’s prog, isn’t it: either magical or boring. If it’s neither then it’s not proper prog

Dave Gregory

Esoteric instincts were in full control by the time XTC recorded third album Drums And Wires in 1979. With angular, fidget-funk assaults like Scissor Man and Helicopter alongside the warped, krautrock-tinged rumble of Millions and the deeply creepy whisper-to-a-scream of Complicated Game, this was music that existed in an entirely different universe from the strutting, art school tail-chasing of most new wave acts.

Now with mercurial six-stringer Dave Gregory – later a member of the Prog-approved Tin Spirits – in the ranks, Partridge and Moulding were able to take their songs in any direction that felt right, regardless of the meagre creative spectrum approved by what Partridge refers to as “punk’s Year Zero mentality.”

“When we played Battery Brides on stage, the instrumental machine noise section in the middle used to go on for ages, and that was pretty out there for the time,” Gregory says. “Some nights it worked better than others. It was a great one to play – we used to go off into a trance and Andy would improvise this long guitar solo while I played this ostinato riff through a very fast digital tremolo effect. Some nights it would be quite magical and others it would be pretty boring! That’s prog, isn’t it: either magical or boring. If it’s neither then it’s not proper prog!”

While the 80s’ most successful artists slavishly embraced the stodgy sonic trademarks of the age, XTC spent the decade producing an extraordinary series of albums that dared to be both wildly imaginative and compositionally timeless. From the muscular, dark rock of 1980’s Black Sea, with its terrifying closing epic Travels In Nihilon – surely among the decade’s most subversive and progressive pieces of music – to the pastoral gleam of 1986’s Todd Rundgren-produced masterwork Skylarking; and on to the genre soup of 1989’s Oranges & Lemons, XTC were a major label band that had occasional brushes with the pop charts, but steadfastly refused to hold back when it came to exploring music’s endless possibilities.

Their Dukes Of Stratosphear records are actually better than the psychedelic records they were pastiching

Kavus Torabi

“People would always ask, ‘How would you classify the music?’ I wouldn’t know where to begin,” says Gregory. “There were definitely progressive elements in there. We never got into that awful trap of having to follow up a hit single, so in that way we were always prog. Andy’s a very inventive guy and was always thinking ahead. As soon as there was any kind of threat of the band being put in a box, he’d be thinking outside it.”

“I think they’re my generation’s Beatles,” states Torabi. “They went right out to the outer regions and it was all brilliant; and yet it always sounded like XTC. Travels In Nihilon is their Tomorrow Never Knows. It’s probably my favourite song of theirs – but what is it? Where did that come from? It predates Sonic Youth by about five years. It’s just amazing, an incredible piece.

“Then listen to their [psychedelic side-project] Dukes Of Stratosphear records. They’re actually better than the psychedelic records they were pastiching; not a duff track anywhere! XTC were such a brilliant and pioneering band in so many ways.”

Although XTC are no longer active, their music continues to influence and delight new generations of musicians and fans. You can hear shades of their pristine, crafted songwriting and exquisitely intricate arrangements in everyone from It Bites and Field Music to Knifeworld and Primus (who memorably covered Scissor Man on their 1998 EP Rhinoplasty); a testament to the appeal of a legacy that thrums with energy generated by a truly progressive ethos.

I heard a lot of unusual stuff … My brain was at the stage where it was ready to be opened – and it stayed open

Andy Partridge

“When I was a kid I made friends with this chap who was a couple of years older than me, and had much more out-there tastes than me,” Partridge recalls. “I already loved The Beatles and British psychedelic pop; but he was importing stuff, a lot of jazz like Tony Williams’ Lifetime, the Emergency! album, and Mothers Of Invention records.

“I was being exposed to things like We’re Only In It for The Money, which I still think is a masterpiece. I heard Captain Beefheart’s Safe As Milk emanating from my friend Dave’s brother’s bedroom. I heard a lot of unusual stuff on strange radio stations, too. My brain was at the stage where it was ready to be opened – and it stayed open!”

Initially reluctant to concede that XTC were a bona fide prog band, while speaking with Prog, Partridge reassesses the situation and warms to the idea. “Oh, there’s That Wave, from our Nonsuch album, for a start,” he notes triumphantly. “My guitar was in a very strange tuning, which I can’t even remember. Then there’s Easter Theatre [from 1999’s Apple Venus Volume 1], which has proper movements in it – and not of the bowel variety! It’s firmly in the progosphere.

“Then there’s Garden Of Earthly Delights [from Oranges & Lemons], which is progsational! Colin is a prog offender too, I’d say. Deliver Us From The Elements [from Mummer, 1983] for instance: the synthesizer, the Leslie guitar, the Mellotron choirs and the backwards guitars washing over it and making it sound like a storm. Pretty damn proggy!”

Square pegs to the last, XTC never achieved the commercial success their music deserved. And yet, if being progressive means pursuing a unique path at all costs and producing astonishing music along the way, they qualify with room to spare.

“I’ve really damned myself, haven’t I?” Partridge reflects. “But the more I think about it, we were pretty progtastical. I’m quite happy with that.”