Don Felder joined the Eagles just as their career went stratospheric, co-writing Hotel California and assuring his place in music history. In 2018, as the guitarist released his third solo album American Rock’N’Roll, he spoke to Classic Rock about his dirt-poor childhood, the enormous impact of Woodstock and the ups and downs of life in one of music’s most combustible bands.

For Don Felder, the bomb went off during the second weekend of August 1969. He and 500,000-odd other freaks, dropouts and rock’n’rollers had descended on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in upstate New York for the Woodstock festival, the point where the burgeoning counter-culture reached critical mass. They say if you can remember the 60s you weren’t there. But Felder remembers the 60s, and he especially remembers Woodstock.

“I was there,” he says. “I saw Jimi, I saw Janis, Santana, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Hundreds of thousands of people just having a great time. It was the biggest explosion in the history of American music. The debris was cast up into the atmosphere and around the world. Woodstock infected the entire planet. Everything that came after it was a result of that contamination.”

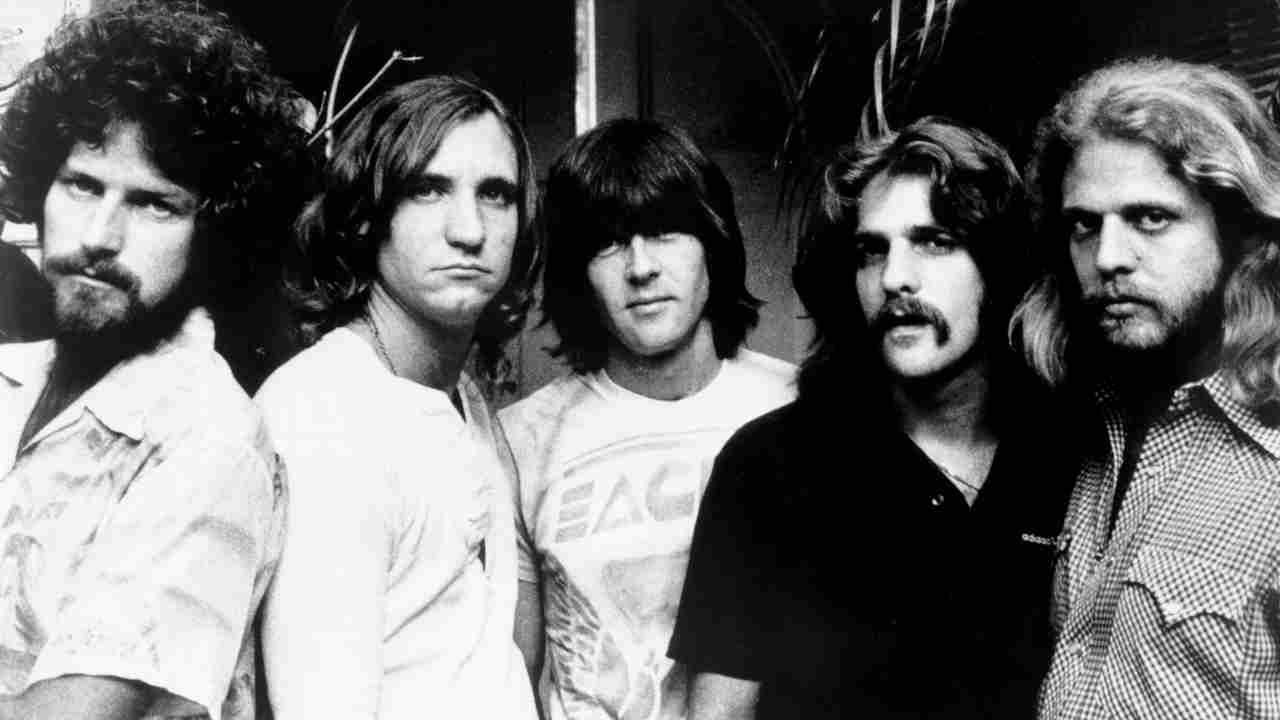

If he sounds like an evangelist for rock’n’roll, that’s because he is. And one who hauled himself out of poverty to play his own significant part in this ongoing revolution at that. He’s part of a cluster of musicians from Southern Florida who emerged at the same time and went on to alter the course of music in their own unique ways. He was the guitarist brought into the Eagles to give them a rock’n’roll edge, and the man who sparked off the song that would assure them of immortality, before not one but two bitter splits left him out in the cold.

Today, 50 years after the Woodstock Big Bang, Felder remains a true believer. His new album, American Rock’N’Roll, celebrates what he sees as one of the great modern art forms. The cast of A-list guests he has assembled for it includes Slash, Sammy Hagar, Mick Fleetwood and the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir, testament to Felder’s standing as one of the most under-appreciated guitarists of his generation. And if his relationship with his former band remains complex, it hasn’t tainted his pride in either the Eagles’ contribution to rock’n’roll or his contribution to the Eagles. “It’s been a good journey,” he says. “An interesting one.”

Felder grew up poor in the dirt and heat of Gainesville, Florida. “Literally right next door to destitute poverty,” he says. Like so many kids of his age, it was the sound of Elvis Presley rattling from a cheap transistor radio that changed his life. “He’s the one who started it all for me,” he says.

One day the young Don and his brother were exploding cherry bombs near their house when a neighbourhood kid came out to investigate what the infernal noise was. Don said he’d swap some of the firecrackers for the battered acoustic guitar he knew the kid had. “It had missing and broken strings, but that didn’t matter to me,” he says. “I found a guy two or three blocks away who showed me how to string and tune the guitar.”

There wasn’t a music store in town. Even if there had been, the Felders couldn’t afford guitar lessons for their son anyway. So the young Don spent hours and hours listening to music on an old tape recorder, teaching himself to play by ear. “I could hear something over and over and figure out where that person was playing on the neck of the guitar,” he says. “I could just see it in my head. Even today I can hear something two or three times and play it.”

Music promised a path out of poverty, and Felder became obsessed with following it. He would spend hours jamming after school, until his parents returned from whatever jobs they were holding down.

There was another kid at school who had the same drive. One day this kid turned up at a frat party, acoustic guitar in tow, to watch the band Felder had put together.

“He started playing and singing, and his voice was so good and his playing, rhythm-wise, was so great that I said: ‘You need to be in my band,’” says Felder.

The kid’s name was Stephen Stills, and Felder asked him to join his band, The Continentals. It was the start of a relationship that endures to this day. “Stephen is one of my best friends,” says Felder. “He’s been there whenever I’ve needed him.”

The ambitious Stills left The Continentals after a year. His replacement was another young guitar hotshot, a curly-haired California transplant named Bernie Leadon. “He’d just turned sixteen, and had a driver’s licence and a car, so that was useful,” Felder says of his future Eagles bandmate.

Florida in the early 60s was just as much of a hothouse for future rock’n’roll talent as New York, San Francisco or Los Angeles. Maybe more – where those coastal metropolises acted as magnets, the southern states had their own developing musical ecosystems.

Gainesville had Felder and Stills and Bernie Leadon. Up the road in Jacksonville, a bunch of roughhouse kids led by a teenage hothead called Ronnie Van Zant were putting together their first band, My Backyard, who would cycle through a bunch of names before settling on Lynyrd Skynyrd. Over in Daytona Beach were The Escorts, led by brothers Duane and Gregg Allman and rapidly establishing themselves as the kings of the local scene.

“We were always in battles of the bands together, and they won every single one,” Felder recalls of the Allmans. “If I was going to lose a contest like that, I couldn’t think of anyone I’d rather lose to.”

Felder and his bandmates would crash at the Allman boys’ mother’s house to save money on hotel rooms. It was Duane who taught him to play slide guitar, an instrument Felder would make his own during his Eagles heyday. “He was sitting there playing slide one night, and I said: ‘You have to show me how to do that,’” he says. “Still the best slide player I’ve ever heard.”

Felder was working in a guitar store when a blond-haired, sharp-featured kid named Tommy came in one day. Don knew him from high school, although he was a couple of years younger. Tommy wanted to switch from bass to guitar, and Felder ended up giving him lessons. Within a few years Tommy had formed his own band, Mudcrutch. A few years after that he’d upped sticks for LA and changed the band’s name, giving himself premier billing: Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers. By that point, Florida was everywhere you looked.

New York in the winter in 1970 was brutal for anyone, let alone a hick from Florida with nothing but a denim jacket for warmth. The band Felder had put together with Bernie Leadon had fallen apart. Bernie had moved back west to California. Don had packed his guitar and himself and headed in the opposite direction to the Big Apple.

He was a sharp player now. Jazz-fusion was his thing – long, free-form instrumental songs. He was living in a freezing-cold apartment in the guts of Manhattan, decades before it became a byword for gentrification, playing with a band called Flow, who released one long-forgotten album in 1970. He and his bandmates didn’t have two nickels to rub together.

“We were close to starving to death,” he says. “We’d pay fifty cents to get on this horrible train full of junkies and ride all the way up to Harlem, where we were the only white people around, to go to this Chinese-Cuban restaurant where you could get a bellyful of yellow rice with black beans for sixty cents.”

The ambition that got him out of Florida got him off of the breadline in New York. When jazz-rock failed to pay one bill too many, Felder moved again, to Boston. He got a job working in a recording studio, learning how to produce and engineer records, and taught music theory on the side.

He’d stayed in touch with Leadon, and his old friend urged him to move to California. It was the West Coast, not the East Coast, where it was happening – sunshine, grass, great music. Bernie told Don that he’d joined a new a group called the Eagles, a country-rock outfit whose songwriting chops were matched by their drive. When the Eagles passed through town opening for Yes, the two friends hooked up backstage to jam: Leadon on guitar, Felder on slide. Eagles guitarist/singer Glenn Frey was watching from the sidelines, impressed, filing this six-string prodigy in his head.

Leadon’s pestering eventually paid off. Felder packed his gear into a U-Haul and drove from Boston to LA with 600 dollars in his pocket, and crashed on his friend’s floor while Leadon headed off on another Eagles tour. Felder soon picked up work, and played guitar with the opening act on a tour headlined by David Crosby and Graham Nash. When the latter duo’s guitarist got sick, he stepped up to play the parts his old buddy Stephen Stills had originally recorded. Between stints on the road with Crosby and Nash, he would jam with Leadon and his bandmates in their rehearsal room.

It was that connection that prompted the Eagles to call on Felder to come and play slide on Good Day In Hell, a song they were recording for their third album, On The Border. He agreed, and spent an hour or so laying down four or five takes. “The next day I got a call from Glenn asking me to join the band,” he says.

Today, Felder admits that he half-expected the offer, but at the time it wasn’t a nailed-on decision. He was earning $1,500 a week playing with Crosby and Nash – a big chunk of money to give up, especially to join a band who were already notorious for their torrid internal dynamics.

“I had heard from Bernie how turbulent this band was,” says Felder. “He said there was all this fighting over control and power, all that stuff. ‘Do I really quit this great-paying gig to join a band that might break up.’”

In the end it was Graham Nash who persuaded him. “He said: ‘You don’t want to be a sideman for the rest of your life, go join that band.’”

So that’s what Felder did. The poverty he had grown up in would soon become a distant memory, and, for good and bad, his life would be changed irrevocably.

Felder was sitting on the couch of a rented beach house in Malibu when he came up with the idea for what would become the most famous American rock song in history. It was July 1975, and he was 18 months into his stint with the Eagles. They’d notched up their first No.1 with that year’s One Of These Nights, Felder’s first full album with them, and were on an upward swing that would soon gather pace like none of them could have imagined.

Maybe it was the sun glistening on the Pacific waves, or the sound of his infant children playing on a swing on the beach, but a hypnotic chord pattern came into his head. He played it, then played it again, and then again, four or five times. He’d been doing this long enough to know the glimmerings of a great song when he heard them. And this sounded like it could be a great song.

A few weeks later he played a demo of his idea to Don Henley and Glenn Frey, and they loved it. Henley christened it Mexican Reggae, a working title that perfectly encapsulated its sound. Henley and Frey took the song away and wrote a set of semi-mystical lyrics that nailed the cultural, spiritual and metaphysical confusion of mid-70s America. Mexican Reggae become Hotel California, although Felder’s imprint remained, not least in the magnificent twin-guitar solo that sent the song arcing into 30 million desert nights.

For someone from his background, the fame and wealth that came with the Eagles’ success was previously unthinkable. But it came at a cost. The fact that he had a wife and young kids meant he kept away from the worst of the excesses that the band became synonymous with. In his 2008 autobiography, Heaven And Hell: My Time In The Eagles, Felder details his fractious relationship with Henley and Frey, the band’s alpha males, sarcastically calling them “The Gods”. Today he’s sanguine about the turmoil of life as an Eagle.

“It wasn’t about ego,” he says, not entirely convincingly. “It was really about pushing the quality of the singing and the writing and the playing. Just pushing it up notch after notch.”

He flat out refuses to talk about the point where it all started to go wrong with the band. “Let’s keep it bright,” he says tersely. But it’s all out there anyway: how personal animosity and heavy-duty drug use combined to turn an already toxic atmosphere terminal.

The end came during an Eagles show at Long Beach Arena on July 31, 1980, when a furious Glenn Frey threatened to beat up Felder as soon as the band got off stage. Remarkable footage shows an incandescent Frey hurling a bottle at the guitarist’s speedily departing limousine.

Felder’s post-Eagles career got off to a flyer. He wrote the theme tune for the cult 1981 animated film Heavy Metal, played guitar on albums by Stevie Nicks and Diana Ross, and, in 1983, released his debut solo album, Airborne. And then Don Felder stepped away from music.

“I made a conscious effort to stay home and be a father to my children,” he says. He made packed lunches and drove carpool, was commissioner for a little-league baseball team and a soccer coach. It was a comfortable life, a world away from his old existence with the Eagles. He occasionally made appearances on film soundtracks and played the odd session gig, but mainly he stayed out of the limelight. When Don Henley offered him a spot as his touring guitarist in 1985, he turned it down, partly because he didn’t want to be away from his family and partly because the 5,000 dollars a week seemed like a fairly derisory sum.

All that changed in 1994, when country star Travis Tritt covered Take It Easy for an Eagles tribute album. At Tritt’s request, Felder and his former bandmates got back together for the video.

“We’d tried, unsuccessfully, several times to reunite,” he says. “But it finally came together around that video. We were all the same room, hanging out and shooting pool and telling jokes. It was like: ‘Hey, this isn’t so bad. We could do this again.’”

The inevitable reunion came a few months later, heralding the Eagles’ money-spinning Hell Freezes Over tour. “It was joyous,” Felder says. “Happy. Very warm.”

But this great American soap opera thrived on drama, and by 2001 Felder was once again out of the Eagles. A dispute over royalties escalated into a series of law suits and counter-suits, eventually settled out of court. In 2008 Felder published his autobiography, which featured unflattering portraits of his old colleagues. It reopened old wounds wider than ever before and closed the door on his old band. Felder has never played with the Eagles since. In the middle of his dispute with the band, his marriage broke up. “I lost my band and my wife,” as he put it.

His belated second solo album, 2012’s Road To Forever, was the sound of a man finally ready to re-enter the ring after having taken a psychic battering. His latest album, American Rock’N’Roll, ups the game. For Felder, the all-star approach captures the spirit of the old days.

“Back then we’d be in this complex in Miami, five different studios all connected by the long hallway,” he says. “The Eagles would be in one, Chicago in another, the Bee Gees in another, Stills or Clapton in another. You’d walk down the hallway to get a sandwich, and someone would say: ‘Felder, what are you doing here? You gotta play on this record’, and you’d work until four or five in the morning.’”

American Rock’N’Roll is never going to scale the same heights the Eagles did, but Felder says that’s not the point. Instead it’s a way of closing the circle, of paying tribute to where he came from.

“Music has been a stabilising force in my life since I started playing when I was ten years old,” he says. “It’s gotten me through hard times, through destitute poverty growing up in Florida, through nearly starving in New York, through all the ups and downs. It’s been the one constant. It’s been my one passionate lover.”

Published in Classic Rock 263