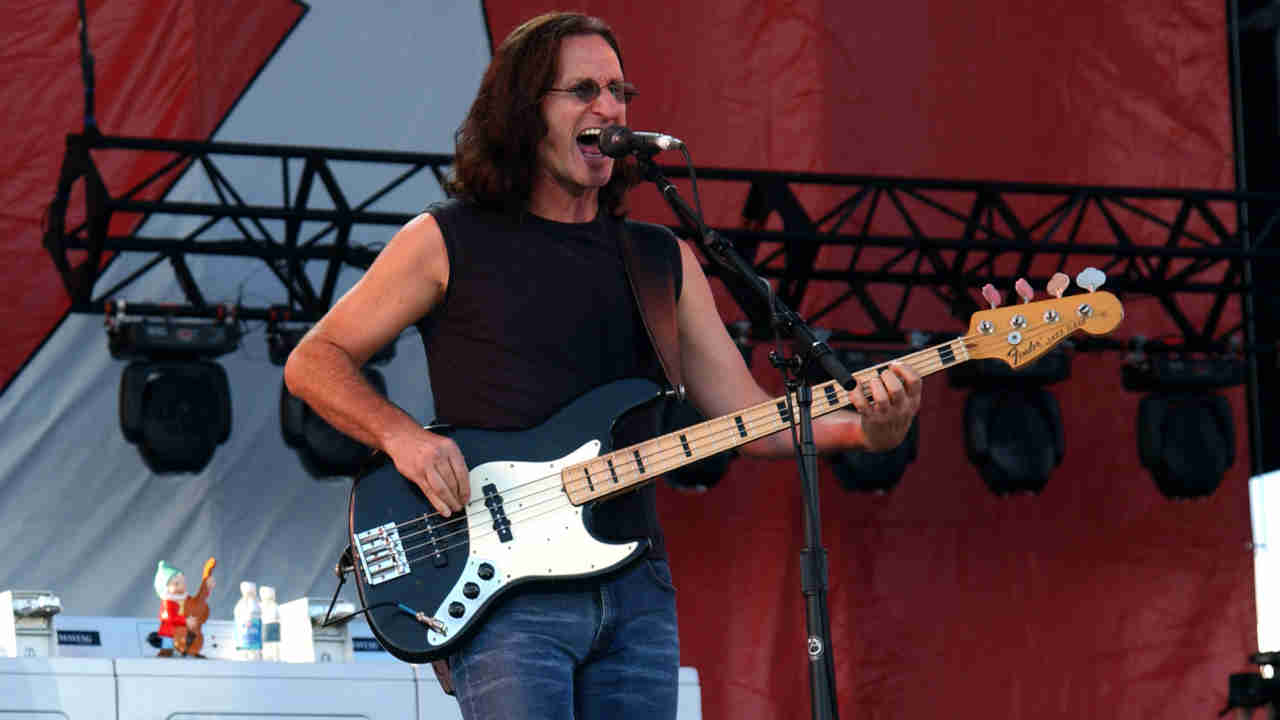

Part of Rush’s legend was built on the landmark live albums they made, including 1976’s All The World’s A Stage, 1981’s Exit… Stage Left and 1989’s A Show Of Hands. In 2003, as they prepared to release the in-concert album and DVD Rush In Rio, Classic Rock sat down in Toronto with bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson to look back over their career as a live band.

“It was all people, there was no horizon,” says Rush’s Geddy Lee. His bandmate, guitarist Alex Lifeson, concurs: “People were everywhere you looked.”

On July 30, 2003, almost half a million punters watched Rush play a 35-minute set as the sun set over Downsview Park, a former military base outside Toronto. The event – officially called Molson Canadian Rocks for Toronto but nicknamed SARSstock or SARSapalooza on bootleg T-shirts – lasted 11 hours and was headlined by The Rolling Stones, and the bill also included AC/DC, The Guess Who, The Isley Brothers and, of course, Rush.

Organised by local politicians to give the ailing city a boost after a SARS outbreak caused 42 deaths and hit its tourism trade to the tune of around two billion Canadian dollars, the concert was a strange culmination to Rush’s first tour for five years.

The Stones started their set that night with a typically ebullient Mick Jagger telling the crowd: “We’re here, you’re here and Toronto is back and it’s booming!” Well-practiced hyperbole it might have been from Jagger, but the sentiment could have been just as easily applied to the local three-piece who had preceded The Stones earlier in the evening.

Toronto is Rush’s town, though they’re far too reserved to make that kind of judgement call, and would probably look away distractedly if you mentioned it. But each time the city’s baseball team – the Bluejays, whom Geddy follows with a misplaced ardour – hit a run the giant Skydome stadium PA bursts into life with the spiralling riff from The Spirit Of Radio.

“The Stones’ people called us because they felt it was important to be on the bill as we’re a Toronto band,” Lee says. “And it’s not the kind of thing you can say no to. But we were in no position to say yes, because we weren’t even on the road; we couldn’t have been more separated.”

“Geddy was in France on holiday with his family, I was down south taking a break, and Neil [Peart, drummer] was at home in California,” Lifeson elaborates.

It’s a breezy Saturday in October at Rush’s management office in Toronto, and although the sun is shining it’s deceptively cold outside. It’s just before midday, and Geddy’s dog Duke is snuffling at the low table between Alex, Geddy and I, attempting to wrest a croissant from a plate piled high with them. Geddy pulls him aside with gentle admonishment, and Duke falls into an almost immediate sleep on the low sofa.

Knowing the band had around 40 minutes of stage time to fill at the show, they toyed with playing 2112 in its entirety, but dismissed the idea when, as Lee admits, “we realised that it wasn’t our crowd”. Instead they opted for a set list that included Limelight, Tom Sawyer and Dreamline; songs, in essence, most recognisable to an audience who may or may not know their catalogue. Working Man was to be their encore, but in the tumult of a huge multi-band bill and the machinations of a dozen bands and crews sharing one stage, Rush’s encore was, Lifeson admits, a fiasco.

“It was a little crazy backstage,” he says. “We were getting ready to go back on and they put the house music back on. By the time they figured how to turn it off again the crew had already taken half the gear off.”

“I loved it, myself. I just had a terrific day, a real treat,” Lee says, savouring the memory. “Some of the artists were a little uptight for some reason, but I thought it was the coolest thing, you know.”

Rush are about to release their fifth live album, Rush In Rio, on CD and DVD. Lee calls it their “accidental” live album, coming as it does on the back of the DVD itself. It was only during the mixing of the live footage that it was suggested they also make the music available on CD, so that, as Lifeson says, “people can listen to it in their car, too”. But it would take a full tank of petrol and a lot of road to travel a three-disc journey that spans the band’s almost 30-year career.

The album begins with Tom Sawye’ and ends, unlike the DVD, with ‘Vital Signs’. In between it rages and dips, from By-Tor And The Snow Dog to a wonderfully accomplished acoustic reading of ‘Resist’. Neil Peart does terrible, possibly cruel things to his drum kit for his eight-minute-plus solo, O Baterista. And the Brazilian audience confound expectation and the laws of physics by somehow managing to sing along note-for-note to the convoluted instrumental ‘YYZ’.

The fact that Rush managed to complete a new studio album – 2002’s ‘Vapor Trails’ – and a 66-date tour to back it up, which resulted in the new live album and DVD, is a story in itself. After an enforced five-year hiatus after Peart lost both his daughter and then his wife in less than a year, Rush didn’t know if they would ever perform together again. In the summer of 2002, however, Lee, Lifeson and I had sat in this same room, and Lifeson had explained how Peart had to learn to play with the band again after he hadn’t touched his drums since the death of his daughter. They were upbeat and determinedly resolute, although Lee shared his misgivings about taking on a lengthy tour as he approached the age of 50. Lee and Lifeson both reached that milestone this year; Peart is 51.

Watching the DVD – or Rush live, as I did at Madison Square Garden in New York in October last year – you wonder quizzically in the face of this fact, and metaphorically scratch your head in disbelief. The collective euphoria coming from the stage for the duration of the three-hour show was dense and dramatic: grins are swapped; silent, happy nods exchanged with one another and with the first few rows of the audience visible from the stage; dextrous, goofy (Lifeson’s adlibbed speech about the music in his head on the night I saw them was pure delirium, causing the usually stone-faced Peart to break into a wide grin) and utterly at ease with the situation and themselves.

“I made that up; I make them up every night. I get very nervous just before I talk, it’s terrifying,” Lifeson says when I mention his monologue.

Geddy Lee smiles. “I love that bit of the show,” he says. “They’re great, aren’t they? It’s my favourite part of the night.”

On disc two of the new DVD there’s a documentary on the band, called (almost inevitably) The Boys In Brazil, a hand-held-camera, on-the-road piece that follows Rush through their final three shows in South America, culminating with the show in Rio de Janeiro. It’s held together with some sharp editing and a series of band interviews that are both eloquent and funny. Rush take their music very seriously, but thankfully refuse to take themselves seriously at all. In The Boys In Brazil Lifeson and Lee mug their way through their interviews, cajoling each other. Though more reserved, Peart is upbeat, chuckling quietly. In every other shot of him on the entire DVD he’s either playing drums, warming up to play drums or slumped somewhere with a weathered paperback in his hand – just as you would imagine he might be.

The roaring, sold-out success of that tour reignited Rush’s desire to be a band again, something that was very much in doubt the last time we spoke. Now, it looks likely there’ll be two more Rush studio albums before they think about calling it a day.

2004 marks 30 years since Rush released their self-titled debut album in America. Back then, of course, they’d play a string of support shows with sets shorter than an hour. In between those dates they’d set up at local high schools or clubs and play their own minuscule headline shows; the next night they would be 300 miles away, opening on a three-band bill. On average they were playing around 250 shows a year.

“Those were the opportunities,” Lifeson says without a hint of rancour (Rush rarely do rancour). “We’d play Cleveland as the opening act, then come back a week later and play the local club as a headliner. And that would happen a few times in the course of a year.”

One of the hidden highlights of the new DVD is footage of the band shot around that time. Out promoting their second album, Fly By Night, they had the opportunity to step up from support band for the night and headline their own show at a school somewhere in the south – the details are sketchy and remote. Chancing upon a stage set constructed for a school play which – judging by the cardboard turrets and towers – leaned heavily towards Arthurian myths for inspiration, and using a bulky camera, the band decided to make their own clip for Anthem: three fresh-faced youths strutting around and staring into the camera, the set shimmering slightly amid the cacophony. It’s wonderful, revealing stuff. A lot of bands, you marvel, would have left such footage at the bottom of the box.

Rush released their first live albums, All The World’s A Stage, in 1976. It was recorded over three nights in June the same year at Toronto’s Massey Hall at the end of the North American 2112 tour.

“Massey Hall is right around the corner there, actually,” Lee says. “The title – Shakespeare, obviously. That was Neil’s idea. The cover shot was our live set up at the time – the starman logo, the drum riser…”

“How long had we been out on tour then?” Lifeson asks, a crease suddenly forming between his eyebrows. “I don’t know, everything was done in such a hurry in those days. I remember coming home at one point to record Fly By Night before that – and we did that in five days.”

“Ten days,” Lee says, with some conviction.

“Oh, I thought the next one was ten days?” Lifeson pulls himself back on to the sofa, dates tumbling through his memory. “So we did that and went out for a year. And then how long did we get to do Caress Of Steel?”

“A whole month,” Lee says dryly. “Actually, no, three weeks. And that was a total indulgence, it seemed like forever. That’s why that record’s so weird.”

The Caress Of Steel album was the first time the band got graphic artist Hugh Syme to create the album artwork. He’s had a hand in every one since.

Geddy: “He came to our attention because he was a local musician [he plays keyboards on the 2112 song ‘Tears’, among others] who was also an artist. Neil and him hit it off straight away, as you can imagine. And we all really liked what he did with Caress…. It just became so much easier to hand over the responsibility to him. He always comes up with great ideas, so we let him.”

The liner notes for their second live album, Exit… Stage Left, in 1981, suggested a band with an inured ethos and, for a group of men still in their early 20s, a self-assurance and aspiration that looked certain to keep them in good stead as they strode off purposefully towards the future. ‘This album to us,’ the inner sleeve notes trumpet, ‘signifies the end of the beginning, a milestone to mark the close of chapter one, in the annals of Rush.’ Not a bit of it.

“I don’t think we knew what the hell was going on. We were just happy that we were still around after 2112,” Lee admits. “Before we did that we figured that that was probably going to be it; we couldn’t predict how successful that album would be, how well received it was going to be. We were in a lot of debt going into make 2112, so we figured, what the fuck, if we’re going to go out then let’s go out doing exactly what we want to do – a 20-minute song about priests! Pretty normal.

“The good thing about it,” he says, “was that the album was so weird that nobody knew what to do with it at the record company, and because it was successful they just left us alone for the rest of our careers.”

Although 2112 gave Rush the commercial foothold they so desperately needed, they didn’t play it in its entirety again until they went out on the Test For Echo tour almost 20 years later.

“That was a leap of faith, playing that live again,” Lee says. “We were like, can we do this, can I sing it? Very weird to rehearse that, too. And then when we got into it, it was so much fun to play.”

“A real high point of the evening,” Lifeson agrees with an emphatic nod. “And every night when we went out to play it there was just this vibe,” Lee says. “We got right back into that old head space much easier than I ever would have imagined – those young kids playing that song.”

One of the highlights of both the new album and DVD is the acoustic reworking of Resist, which first appeared on the Test For Echo album; live it had followed the original fairly closely until the Vapor Trails tour. And while placing an acoustic song in their set seemed like the most obvious thing to do, both Lifeson and Lee admit that that was very much the reason they chose to resist doing so. In the DVD interview, Peart recalls the afternoon the others told him to come in a little later as they wrestled with the idea of taking the heart out of a song but keeping its soul.

Lee: “Oh, that was really weird at first. We’ve talked about that kind of idea for years and we’ve never tried it. It’s like we talk about it every time we go on tour: ‘Well, let’s do an acoustic thing…’ Finally we said alright. And when we were listening to Resist I heard it in a whole new light. I thought, this is really a folk song that we’ve jazzed up with all this instrumentation, but if you stripped it right down then it’s a lovely little folk song, so why don’t we just try that? We tried it in rehearsal and it was weird at first, but even though it was weird we just kept playing it and before you knew it we fell in love with it.”

In the live set it followed Peart’s astonishing drum solo – viewable as a multi-angle extra on the DVD, and you still can’t follow what he’s doing – and allowed the drummer to rest as Lee and Lifeson positioned themselves at the front of the stage on stools. On the expansive Madison Square Garden stage they looked diminutive; on the enormous Rio stadium stage they look almost lost.

“Oh yeah,” Alex says, shaking off a shiver. “It felt very exposed and naked the first few times we did it like that. It was so unusual to be there at the front of the stage on a stool, without all the stuff around you, just Ged and I, and the crowd looking up at us. It became a real highlight as the tour went on, though.”

They released Exit… when they were coming off the back of the hugely successful Moving Pictures album in 1980. Originally they’d planned to record a live album after Permanent Waves had been released the year before, but their management suggested the band make another studio album before they considered releasing another live record. Something that, in retrospect, “didn’t do us any harm at all,” Lee says.

The live version of Tom Sawyer from Exit… gave them a UK hit, and the tudio version of the song remains a staple of American rock radio to this day.

Lee: “I remember when we finished ‘Moving Pictures’ it was the dead of winter, and my wife was waiting for me in the Caribbean – because we were so overdue to finish the record, they had gone on holiday without me. It was just, come along when you’ve finished. I remember driving back to Toronto in the snowstorm, getting in at four in the morning, packing my bags, going to the airport and flying down there. I was just a wreck. It was a tough record to make.”

“But it was fun,” Lifeson recalls. “We had a really good time making that record. It was a commercial peak for us, too.”

One of Hugh Syme’s original ideas for the Exit… Stage Left cover was to have the tail of Snagglepuss (the 1960s cartoon character whose catchphrase was ‘Exit stage left’) snaking out from behind a curtain, along the album’s gatefold sleeve. But copyright and high costs nixed that idea, and instead the band opted to use the cover stars of their studio albums and position them backstage at a Rush concert: the girl from Permanent Waves sneaking a look out at the full auditorium. It’s clever and evocative and, according to Geddy, cost a lot to make, although as he admits with a sigh: “All our covers cost a lot. Great cover, though. I like it a lot”.

The album was roughly half and half between recordings of some of the band’s UK and Canadian shows. An undoubted highlight is the version of Closer To The Heart recorded at Glasgow Apollo, and the sleeve credits the Glaswegian Chorus for their contribution.

Lee gets very nearly misty at the thought: “That’s one of my favourite memories of touring Britain – playing the Apollo, and the Glaswegians singing their heart out to that song. I think that’s the first time we ever experienced something like that. It was just such an amazing moment that we just had to have it on our record.”

After decades of playing Closer To the Heart, the band had decided to retire the song from their set when it came to the most recent tour, although mysteriously it appears again on both the new live album and the DVD.

“It started in Mexico City, actually,” Lee explains. “We hadn’t played it on the tour, and we can be a bit lunk-headed about changing a show once we’ve worked out what we’re going to play. We didn’t even take into consideration that people had been waiting thirty years to see us in South America, and maybe they have favourite songs they’re going to be disappointed not to hear. Just didn’t think about it. We got there, and we’re in the press conference and they’re asking us: ‘Of course, you’re going to play Closer…”

“It’s the most popular song in Mexico – ever!” Lifeson exclaims, grinning.

Geddy is all mock outrage: “So why didn’t someone tell us that?! We had to go and relearn it the next day in soundcheck, and we played it that night. Thankfully it’s not the most complicated song, it came back pretty quickly.”

While most bands are happy to plug such things as their drums and cymbals sponsors on album sleeve credits, on their new album – along with the Glaswegian Chorus – Rush also gave a nod of thanks to NASA.

“Somehow or other we got invited on a VIP tour of NASA,” Lee recalls, “and when we went down we got on so well with the guys there we just became pals. They were so excited that we took such a serious interest in what they were doing. We would write each other, and then when they heard we were in the area we would go to Houston Space Centre, and likewise if any astronauts were hanging around near gigs. Seriously, they would come to the shows. We would show them around, and they were amazed by the technology – and these guys are seriously into technology, they’re all engineers. One time in London we had this huge party and all these astronauts came and everyone was raving well into the night. It was pretty funny.” He pauses, first to think about it and then for effect: “We’re Rush, we hang around with astronauts.”

“Then we were invited for the first shuttle launch,” Lifeson says. “Countdown [from 1982’s Signals] came out of that, and they supplied all this footage for the video.”

Rush’s third live album, 1989’s A Show Of Hands, was recorded on the tours in support of 1986’s Power Windows and 1988’s Hold Your Fire. A Show Of Hands was the first album the band had produced themselves, to their eventual dismay.

“That was tough. We were really tired by that point,” Lifeson says, deflating at the memory. “We came off tour, went to Europe to record, then we came home and went straight into the studio to mix that live record. And that’s when we really thought we were insane, that this was enough. I remember the conversation, sitting in the back of Studio 3 going through the tapes, and we were all so exhausted. Almost painfully so. We’d done too much, and they were tough tours.”

“They were also really hard songs to play live, and I was feeling the pressure of doing all the keyboard stuff and the bass stuff,” Lee agrees. “It was frustrating me, because I felt that I could never really play because I was so tied down to all the textures. I loved what it was doing for our music, but it was a real price to pay live.”

By the time it came to 1998’s triple-live Different Stages, Rush had curtailed the extent of their touring. With the tour for ’96’s Test For Echo they’d dropped the idea of a support band and opted for lengthy, three-hour shows split into two sets.

Different Stages also came with an intriguing third disc, featuring the band at London’s Hammersmith Odeon (as it was then) in 1978, on the tour to promote A Farewell To Kings.

“It became my job to sift through all the performances we’d recorded on the Counterparts and Test For Echo tours – and we’d recorded almost every night,” Lee says, with a roll of the eyes. “We were finding great performances, but there would be glitches of some kind – a mic would crap-out or whatever. Nevertheless, we were trying to warm up these digital recordings and mix them. I was clearing out my home studio and I found these boxes of tapes that were from Hammersmith Odeon in 1978, and I remembered them.

“At the time, we were supposed to record that show for a radio broadcast,” he continues, “probably the BBC. I had a cold and my throat was so raw, and I felt I didn’t sing very well. So at the end of the night I took the tapes and put them in the dressing room case and said: ‘We’re not releasing this, because I sang like shit’. And I took them home and stuck them in my cupboard.

“Twenty years later, there they were. So we went in the studio together and put them up, and we were like: ‘Wow, that sounds good!’ There are a few songs that are strained, and you can hear it in my voice, and I wasn’t really in key or it was tired or sore. But we figured we could take at least part of it and throw it in as a souvenir for our fans, because there was something about it we liked.”

The Vapor Trails tour ended at the giant Maracana Stadium in Rio de Janeiro on November 23, 2002. It had begun in Hartford, Connecticut, on June 28 the same year, the band having done a day of rehearsal at the amphitheatre the day before. Shed shows, as they’re called in the US, take place at outdoor theatres that are partially sheltered toward the stage but then open out into grassy domes and patches of manicured grass at the rear.

“When we rehearsed, they had it closed off so it looked like a different venue, much smaller,” Lee recalls. “But when we hit that stage they’d opened it all up, so it looked like a totally different venue. It was amazing to look out and see people holding up signs from all over the world. It meant so much to them. And I think that’s the message we got: our music means so much to these people, they would go through this amount of trouble, travel all these miles just to welcome us back. And that was really quite touching.”

Alex Lifeson, too, remains entranced by the memory: “People were crying. It was amazing. We kept stealing glances at each other; it happened a few times, this connection. I remember having a lump in my throat a few times that night.”

Then Geddy Lee looks around the room. “We connected, yeah. That’s when you look at each other, in the moment, and go, this is where we belong.”

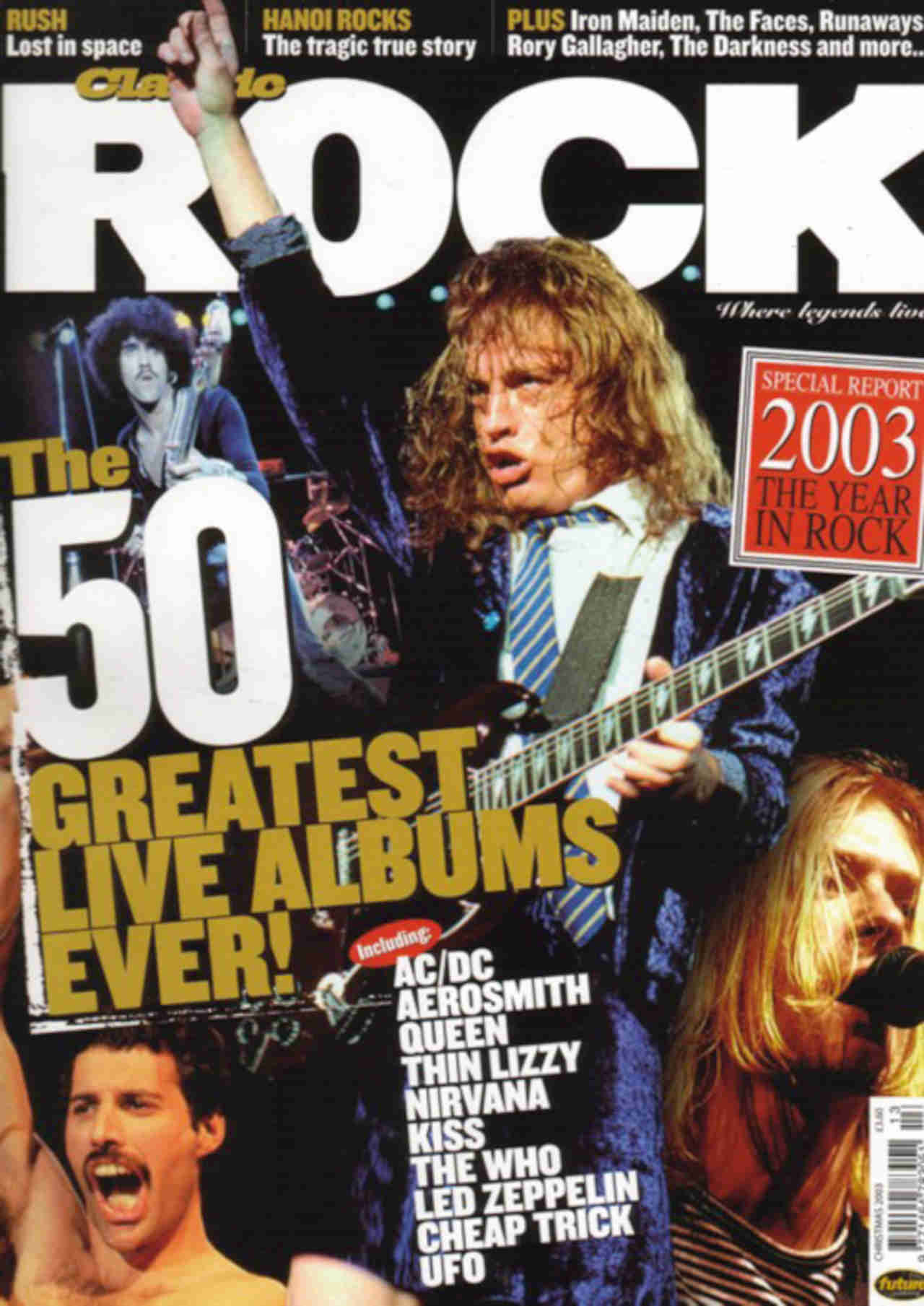

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 61, December 2003