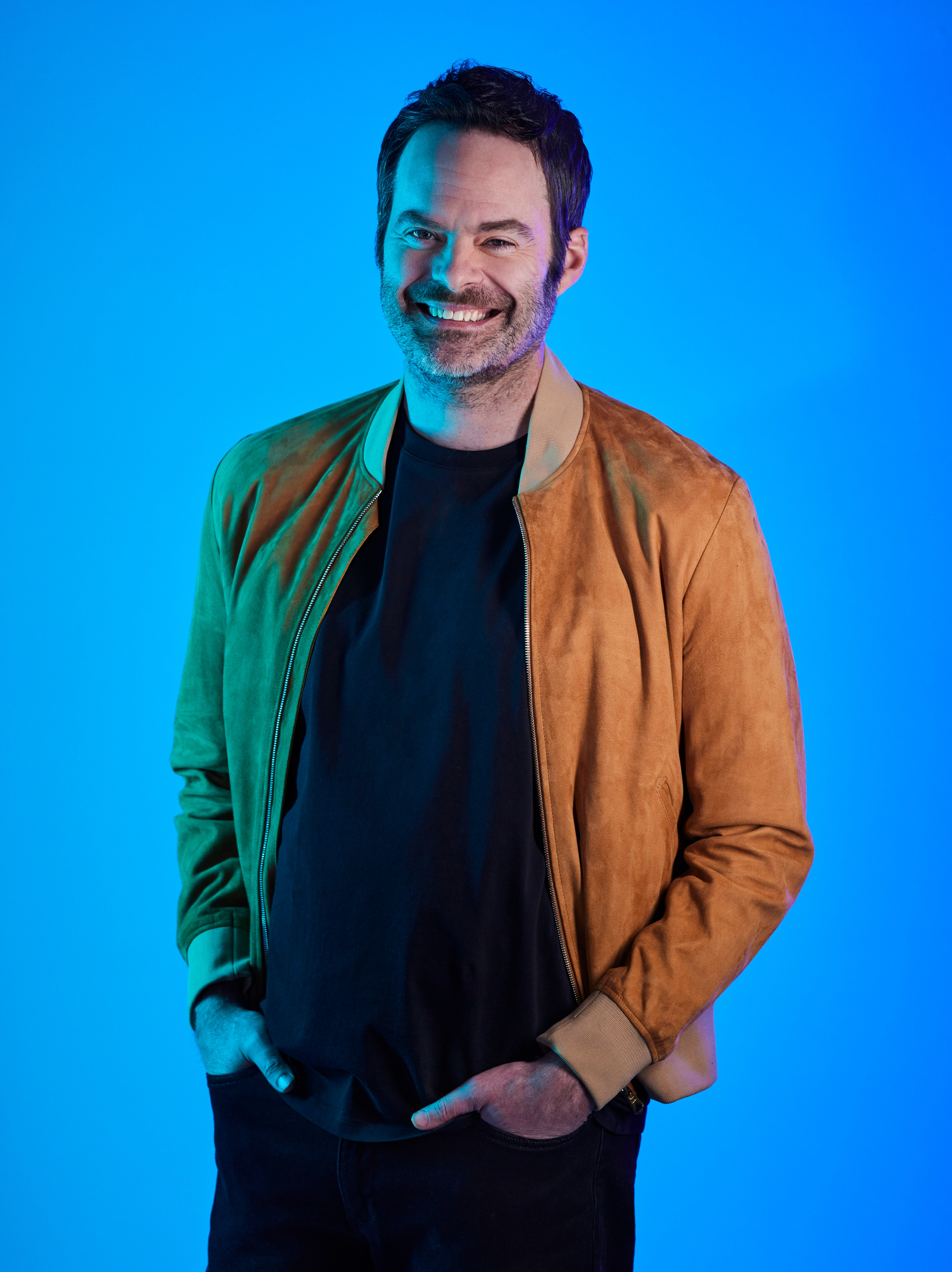

Bill Hader appears on my screen from Los Angeles, unshaven, a little groggy and in an uncluttered white room. Faced with this pixelated version of him, I’m instantly reminded of his role in the 2008 Judd Apatow-produced romcom Forgetting Sarah Marshall, for which he appeared almost exclusively on video call, in the days before Zoom was a thing. “It was such a novelty back then,” he says, that furrowed brow unmistakeable. “It was like, ‘Whoa, this is new.’”

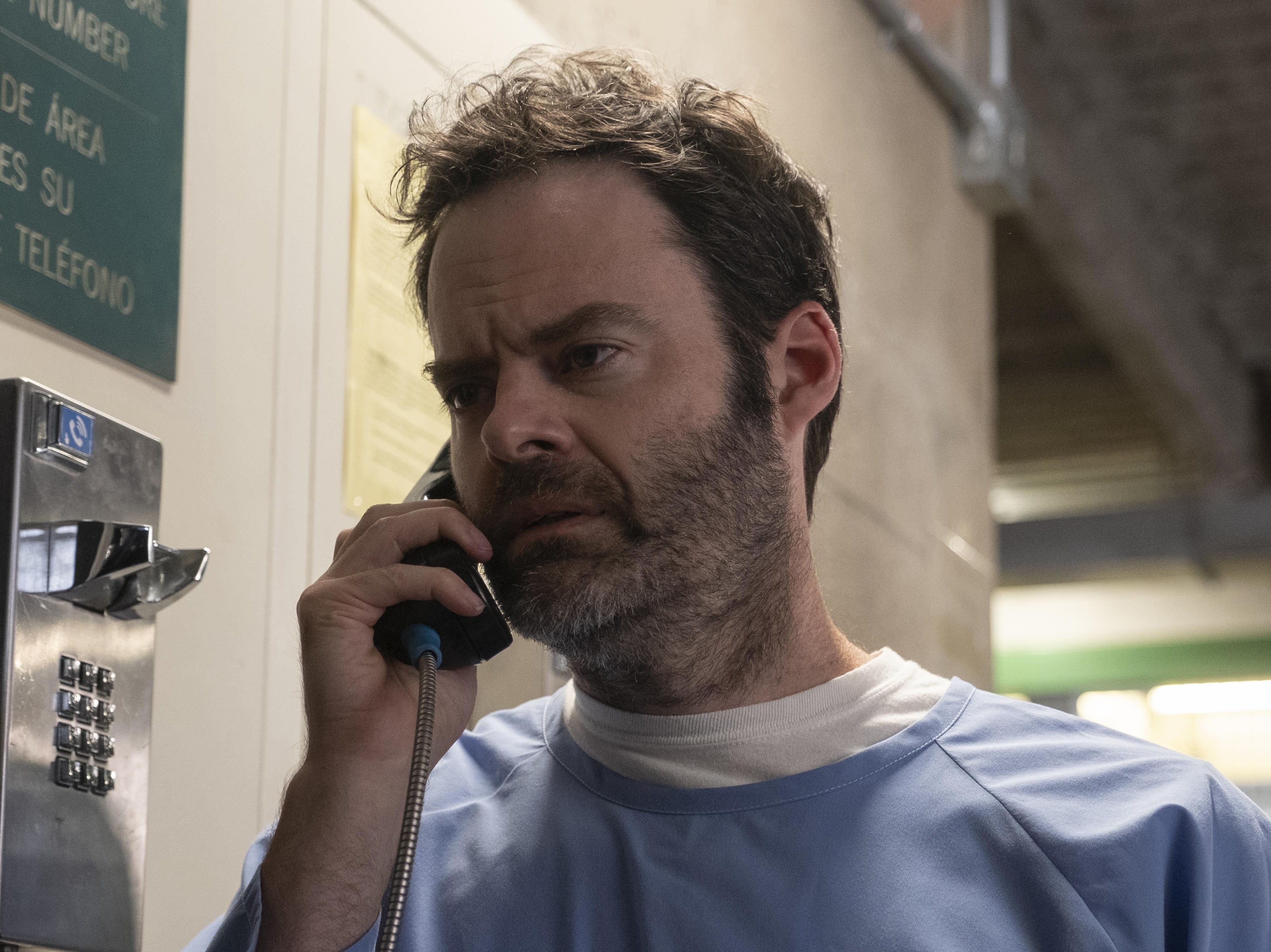

Saturday Night Live’s erstwhile Man of a Thousand Faces is here on my laptop to talk about his greatest creation, Barry Berkman, a marine turned assassin turned aspiring actor in the HBO comedy-drama Barry, which Hader writes and directs as well as playing the title character. The show has won multiple Emmys; critical adulation; obsessive fans. What began as an apparent riff on the hitman-with-a-heart-of-gold trope has evolved over four seasons into something richer: a thrilling synthesis of showbiz satire and character study, with pitch-black humour and nail-biting suspense. As we get to know Barry, the notion of him as simply a stoic, ruthlessly efficient killer slowly dissipates.

“I like the John Wick movies,” says Hader. “But this wasn’t John Wick. This wasn’t ‘assassin’ in a genre sense.” The show was more about “the real idea of a hitman”, he explains. “The loneliness of it, and how murdering people affects his psyche.” Hader points to Tony Gilroy’s 2007 legal thriller Michael Clayton as an example of how to get hitmen right. “I liked that scene when Tom Wilkinson gets killed,” he says. (The hitmen make the attorney’s murder appear to be suicide.) “I always thought that was a good, realistic fixer hit scene. It was so shocking.”

Hader’s face is an orchestra of expressions, all quivering eyebrows, wolfish smiles, and grimaces played for laughs. He is dry and laconic, with a midwestern accent that flits between adenoidal and baritone. He is also, by his own admission, a bundle of anxiety, which seems to manifest itself in moments of quiet self-effacement or hyper-critical introspection. Maybe it’s no surprise, then, that Barry so successfully probes the darkest corners of the human condition while retaining a gloriously offbeat sense of humour.

Not that the end of the last series was particularly funny, as Barry’s sinister past finally caught up with him. “When season three aired, people were like, ‘Wow, it’s not really a comedy any more,’” says Hader. “And I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ And then you go back and watch that last episode of season three, and I’m like, ‘Oh yeah, really funny.’” He’s being sarcastic, of course. As with Breaking Bad, a drama to which Hader says his show is indebted, Barry is very comfortable plumbing the depths of humanity. Abusive relationships, PTSD, mass murder: the series tackles it all, with an unnerving smile creeping out from the corner of its mouth. “I find if there’s a drama that doesn’t have some humour in it, or if there’s a comedy that doesn’t have some sort of real representation of human emotion or something,” he says, “it usually doesn’t work.”

An exception, he adds, is The Naked Gun, which “doesn’t need any pathos – it’s just really funny”. He showed the 1988 film, which stars Leslie Nielsen as a bungling detective, to his three daughters during the pandemic. “I was laughing so hard,” says Hader, for whom watching comedy has always been a family affair. Indeed, growing up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the son of a dance teacher and the owner of an air cargo company, Hader became obsessed with the surrealist farce of Monty Python. “My dad was a massive fan,” he says. “A ton of stuff from Monty Python’s Flying Circus didn’t make sense to me coming from Tulsa.” Although he didn’t fully understand the characters – such as John Cleese’s BBC continuity announcer, with his catchphrase “And now for something completely different” – it didn’t matter. “It only added to the excitement,” Hader says. “There was something very exotic about it to me.”

However much he loved Monty Python, though, it was filmmaking, rather than comedy, that initially drove the young Bill Hader. Long before he was one of the most ubiquitous comic actors of his generation, popping up in everything from Knocked Up to Trainwreck, Adventureland to Inside Out, he had designs on directing movies like those of Scorsese, Terrence Malick and Andrzej Wajda. After attending New York Film Academy in 1996, he spent a few unproductive semesters at the Art Institute of Phoenix and Scottsdale Community College, then dropped out and moved to LA in 1999. Starting at the bottom, he would persevere behind the scenes, directing a short film here, writing a screenplay there, but mostly working as a production assistant on movie sets. Acting was never something he truly considered, until a bad break-up prompted him to start taking classes at Second City LA, a school that specialised in improvisation and sketch comedy. He was good.

Soon enough, while performing backyard sketch shows in Van Nuys with a group of friends, one of whom was the brother of Nick Offerman from Parks and Recreation, Hader caught the attention of Megan Mullally. The Will & Grace star – and Offerman’s wife since 2003 – was so transfixed by Hader that she recommended him to SNL creator Lorne Michaels. Hader, who was working as an assistant editor on a cookery show at the time, nailed the audition, which required three original characters and three impersonations. An eight-year stint on SNL followed, ending in 2013.

If Hader lacked experience, it certainly didn’t show. During his time there, his uncanny celebrity improvisations – from Al Pacino to James Mason – became the fulcrum around which the series revolved. Think of all those characters he developed. The elderly, misanthropic news correspondent Herb Welch. The slack-jawed Californian gardener Devin. The indelibly gaudy nightclub guide Stefon. Last year, Hader explained that SNL had “floated” the idea that he come back to play Stefon – a gay character – but he’d turned it down because of the political climate.

“I was like, ‘I don’t think that’s really a good thing to do now,’” he told The Guardian. “I mean, we had an openly racist, homophobic and misogynistic president, and half the country voted for him – twice! So [those attitudes] are really prevalent.” He went on to say how the idea that people saw the character differently to him had been eye-opening, “because I really love Stefon and it never occurred to me that he would be seen as a stereotype, and that really hurt”.

Since then, though, he’s changed his mind. “Honestly, I don’t know why I said that,” he tells me. “I probably would play him. I think just being asked the question at that point in time kind of made me anxious.” In fact, gay men approached him to express dismay at his comments. “I’ve never had any gay man come up to me and be offended that I [played Stefon].” The opposite, he says, mentioning that he also played a gay man in the 2014 film The Skeleton Twins. “I’ve always had people come up and say how much they love those roles.”

Of all the oddballs Hader portrayed on SNL, only one of them would he put out to pasture: Vinny Vedecci, the loud, unprofessional talk-show host who ticks just about every box on the Italian cliché list. “An Italian woman told me she was offended by it, and I was like, ‘All I’m trying to do is the old comic staple, you know, gibberish and everything.’ And she was like, ‘Right, but my father spoke like that and he actually spoke Italian.’ Your sensibility changes when you get older,” he says. “I don’t think I would do that again.”

Conversation turns to outrage culture. “I sympathise with and understand the sensitivity,” says Hader of the current mood. “But as someone who creates things, I think you want to be able to create things in a genuine way and in an honest way. And what’s happened, especially on social media, is that there are people who aren’t funny, or content that is just offensive,” he says. Meanwhile, other people are making “very interesting stuff that is art. I think the lines have been blurred.”

I bring up Superbad, the ribald, well-received 2007 comedy in which Hader played a cop. In recent years the film has come under greater scrutiny, its boorish teenage sexism and relentless catering to the male gaze leading to a view – in some quarters – that it’s a deeply problematic coming-of-age story. Indeed, an article in the Chicago Tribune in 2018, headlined “How teen comedies like Superbad normalise sexual assault”, dissected a premise that, crudely speaking, is about two horny boys using alcohol to try to dupe women into having sex with them. Add in jokes about menstrual blood and sexual preference, and you can perhaps see why the film has been re-evaluated.

Does Hader think the film in any way condoned the boys’ attitudes? “I haven’t seen that movie in a very long time,” he says. “I’ve heard rumblings, but I’m not on social media, so I don’t really have my finger on the pulse right now. You know, those kids are idiots, like we were all idiots. The point,” he continues, “is that they’re losers and they’re looking for girls and beer and, I mean, that story’s been there for ever. But then, in actuality, the two boys are just in love with each other. That end scene is so funny.”

If “bawdy yet poignant” sums up a lot of Hader’s early films, Barry really is a different beast, a drolly sophisticated series that mixes bathos with brutality. Light relief comes from Henry Winkler’s gregarious drama teacher Gene M Cousineau. I ask Hader if Winkler really is as sweet as they say. “The hardest thing with Henry is that getting him to play an a**hole is very hard,” says Hader, giggling. “Most of my direction to him, genuinely, is to say, ‘Don’t smile. There’s brightness in your eye.’ So, yeah, he is, and he brings a very good cake to the set.” What kind? “Usually a chocolate bundt cake. He gave me the whole history of where the cake came from and what the recipe is. And he really does eat like an 18-year-old. I don’t know how he eats the way he eats. I put on 25lb these past two seasons just from stress and not taking care of myself, and I still don’t eat the way he eats, and he looks great.” He giggles again. “Like, I don’t know what I’m doing wrong.”

Does he struggle with body image? “You know, you have to watch yourself on screen,” says Hader. “And that’s no fun, just in general. I don’t like the way I sound. I don’t like the way I look. It’s just embarrassing. But I’ll be 45 in two months, so the weight thing is more of a health thing now. You go to a doctor and they say, ‘At this age and height, you should weigh this.’” When he was performing on SNL, it was more about vanity, he explains. “I wasn’t used to seeing myself on screen – you go, ‘God I look terrible,’ so you start exercising and jogging and stuff. I still ate like s***, though. Now I have this autoimmune condition, too. I’m just at that age.”

Talking to Hader, you get the sense his brain is a traffic jam of worries. Over the past few years, he’s talked extensively about the anxiety and panic attacks he suffered while on SNL. Neither the critical acclaim nor the awards have helped. “I got that review, and I was like, ‘You know what? My anxiety went away.’ I got an award and walked off stage, and went, ‘Wow. I’m not on fire any more.’” His voice is dripping with sarcasm again. “No, I do have very bad stage fright, and I do get very, very anxious before I have to go in front of a group of people.”

His capacity for self-criticism, he says, can be a double-edged sword. “You should be hard on the work,” he notes. “It’s very good to write it and get all the emotions out, all the feelings, the story, the big, inspired version of it, and then it’s very good to put it away. Because you think, when it’s finished, that you’re a genius. You got to wait for a little bit, a couple of weeks, or a month – you bring it back out and you go, ‘Who the f*** wrote this, this is terrible.’ And that’s a very important part of the process, you know, to be hard on the material.

Being hard on the writing is a very important part of the process

“But then,” he continues, “there’s also a thing that I just have naturally, which is a big self-criticism that can be disruptive in your personal life, that is being hard on yourself, and doesn’t really yield any results. It’s just a cycle of self-criticism that doesn’t yield anything.”

While Hader is candid about his anxiety, he’s less so about his private life. Before our interview, I posted on my Instagram that I was interviewing him. I was suddenly inundated with messages from friends declaring their love for him, and pleading that I pass on their phone number. I tell him. “If they saw me at home,” he says, squirming hilariously in his chair, “all that would fly out the window, but that’s very sweet. Tell them thank you.” Though he insists he’s not aware of his sex symbol status, the internet is awash with stories about Hader, with his ex, The OC actor Rachel Bilson, particularly complimentary about him, calling their break-up in 2020 “harder than childbirth”. After their split, Hader dated Anna Kendrick for a year or so; his new girlfriend is Ali Wong, star of Netflix’s existential new thriller Beef.

Hader declines to discuss his dating life, so I change the subject. Let’s talk about Star Wars, I suggest. Along with Ben Schwartz, Hader is credited as a “vocal consultant” for BB-8, the cute little droid that first appeared in The Force Awakens. He’s happy to oblige in geeking out on the topic.

“My kids love Star Wars and I was so into it when I was young.” He remembers playing with a toy Millennium Falcon in the early Eighties. “I was flying it around my house,” he recalls. “I caught the edge of a wall and it bounced back and hit me in the face. It knocked a tooth out!”

I knocked a tooth out with a toy Milennium Falcon when I was a kid

Speaking about his childhood jolts him into thoughts of his own young family – he had his three daughters with his ex-wife, director Maggie Carey – and how his next move is to spend more time with them. “My girlfriend and I realised that I haven’t had a vacation in 10 years,” he says. “So she and I might do something to reintroduce myself to my kids.”

After all, the Star Wars movie didn’t exactly do that job for him. Hader admits that, in the end, he was barely in it.

“I mean, that’s the weird thing. It was just JJ Abrams being a nice guy. It was like something you would do for someone who won a contest,” he says, grinning. “But it’s pretty cool seeing your name in blue at the end.”

Season four of ‘Barry’ is available Mondays on Sky Comedy and streaming service Now