It’s the evening of July 21, 1993, and Phish is navigating an especially energetic version of Runaway Jim at the HORDE Festival in Middletown, New York. Guitarist/vocalist Trey Anastasio’s masterful, extended solo runs the gamut from quiet meditation to blistering groups of cascading notes, delivered in ways both clever and compelling. But what happens next is perhaps an even greater metaphor for the guitarist’s overall approach to music.

The band segues into Big Ball Jam, an occasional addition to the set where large, colored beach balls are simultaneously batted about by the audience, each color assigned to a different band member. Every time a ball is touched, the corresponding player sounds his instrument. (Luckily, video of this fun spectacle is available on YouTube.)

What results is a spontaneous and beautiful musical cacophony that also serves to create a visceral connection between audience and band. In short, it captures a fleeting moment – something at which Anastasio consistently succeeds in his songwriting and improvising.

The guitarist keeps himself quite busy, splitting his time between his Trey Anastasio Band (commonly known as TAB), solo acoustic tours, performing with orchestras and other interesting side projects. But Phish continues to be at the heart of his musical life, as it has been since its inception in 1983, and so, it will be our main focus here.

One lesson couldn’t possibly cover the totality of Anastasio’s playing, as he draws inspiration from such a wide array of musical styles, from progressive rock and reggae to funk, bluegrass and beyond.

In Between Me and My Mind, the 2019 documentary focusing on a year of his musical life, the guitarist jokingly admits, in regard to Phish, “I don’t know what kind of music this is!” So let’s home in on some of Trey’s most dynamic approaches to soloing and songwriting, along with some music examples.

Here, however, the examples also seek to inspire you to emulate Anastasio in a less literal way by encouraging you to create and develop your own improvised ideas. That might sound a bit scary. But in music, as in life, that usually means we’re onto something worthwhile.

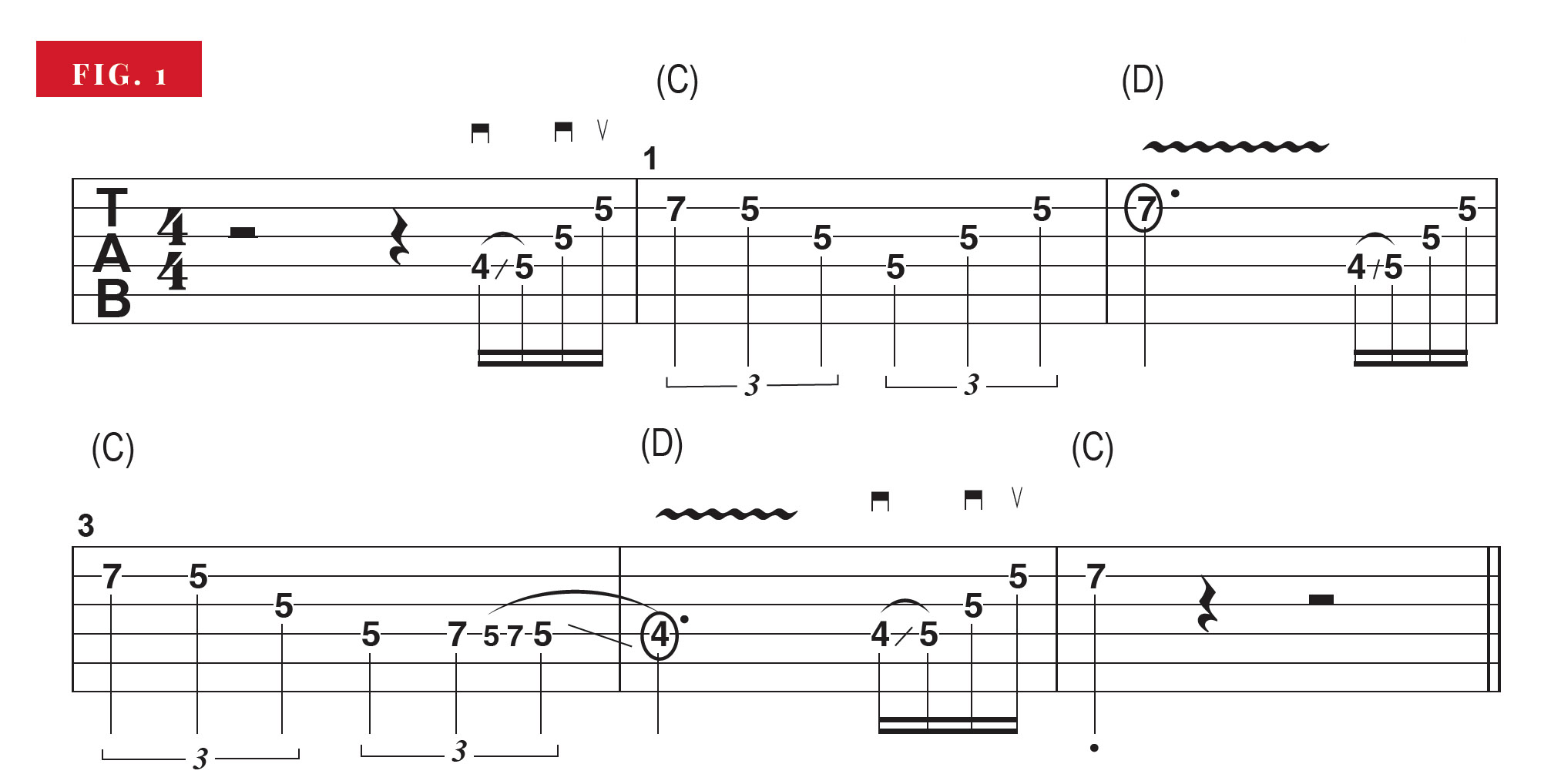

Let’s begin by staying with the very same 1993 live version of Runaway Jim, as Anastasio employs a slew of his favorite improvisational approaches throughout his solo. The song is in the key of D, with the solo section’s basic chord progression alternating between C and D. (Remember, with Phish, the band collectively improvises variations along the way, but we’ll keep things simple by sticking with this progression.)

Figure 1 is inspired by Trey’s phrase at 5:41. The lines here are based on the D Mixolydian mode (D, E, F#, G, A, B, C), which is the 5th mode of the G major scale. “5th mode” means that Mixolydian’s root note, or “home base,” is the 5th degree of the major scale.

So the notes are the same as those that make up the G major scale, the only difference being that they’re orientated around a D root instead of G.

Notice how, in this Trey-style example, a motif (short melodic or rhythmic idea that can be repeated and/or varied) is built from a C major triad arpeggio (C, E, G) and developed.

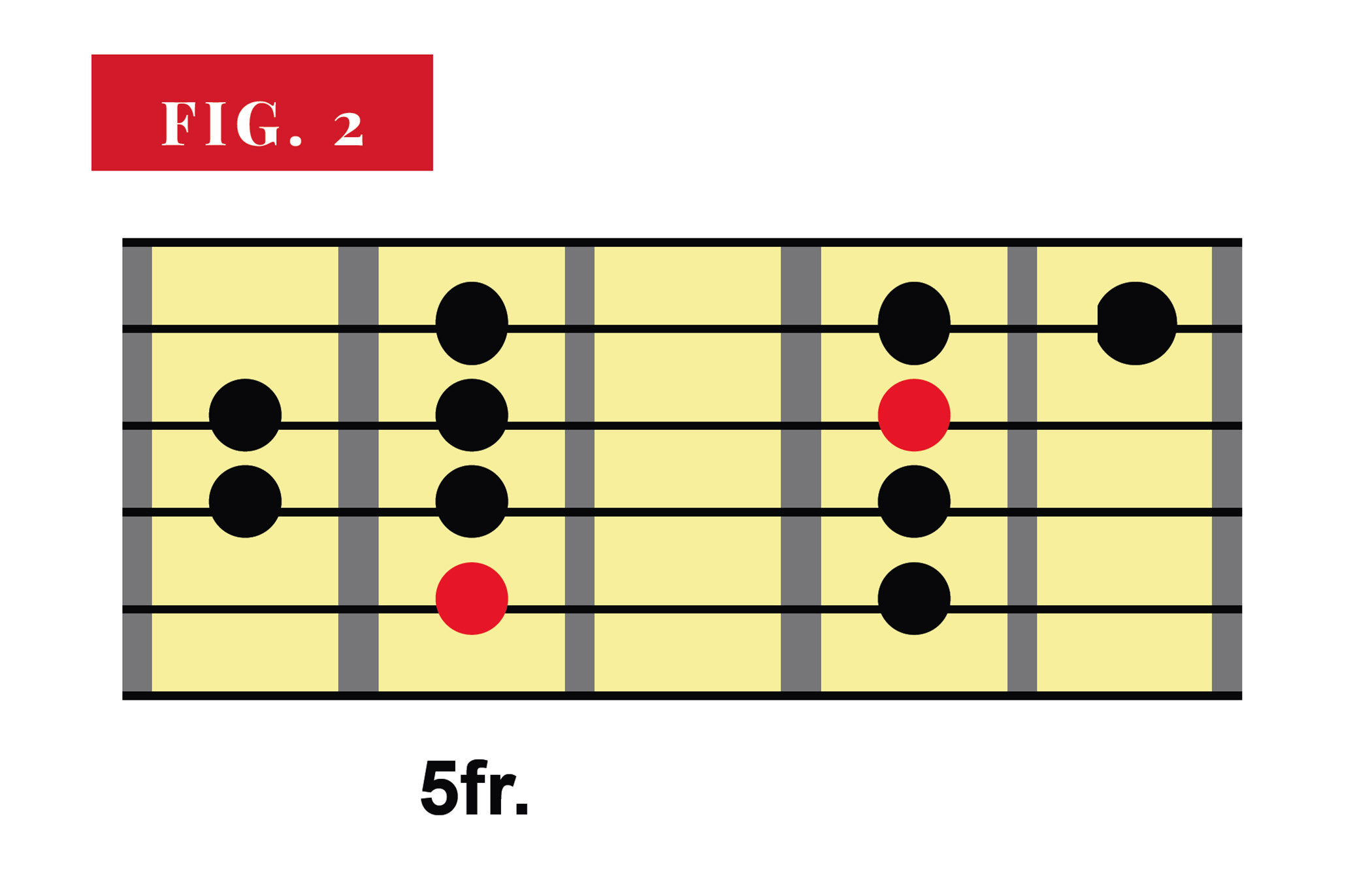

Now let’s explore how we can come up with our own motifs by using the same basic scale shape (Figure 2) along with Anastasio’s motivic approach. Notice in this fretboard illustration that we’re limiting our menu of notes to only those on the middle four strings, with the D root notes highlighted in red.

While creating limitations for ourselves when improvising may seem counter-intuitive, doing so often boosts our creativity, as it’s easier to see and hear variations within a more finite group of variables.

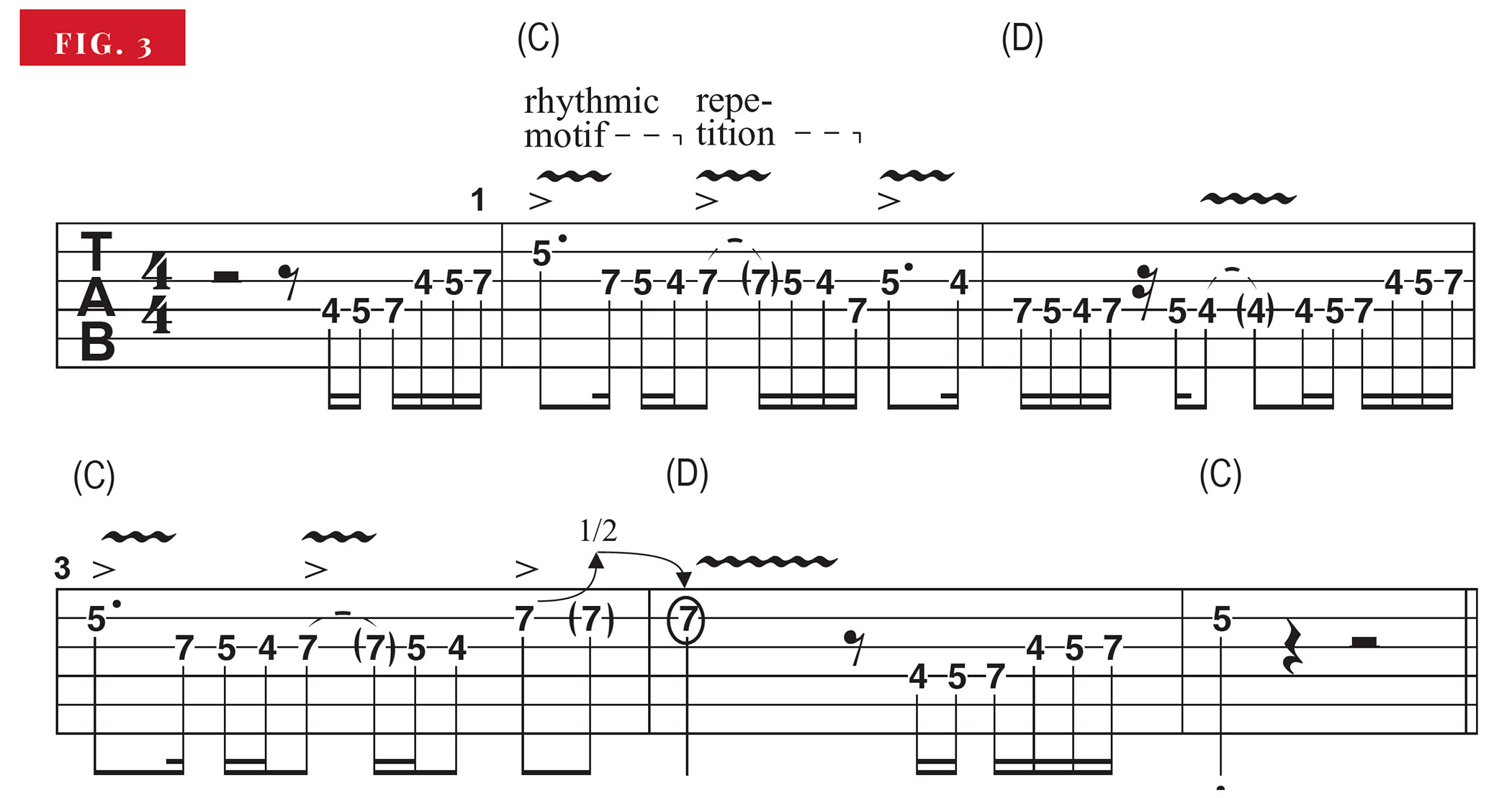

Figure 1 is melodic, using lots of space, so let’s go for something a bit busier and more rhythmic, like Figure 3. Similar to something Anastasio might play, we’ve expanded his opening pick-up motif, and, much as the first example included a quarter-note triplet pattern in bar 1, here we have a busier more syncopated pattern.

(The accent markings above certain notes indicate that they are to be played a bit louder than normal for emphasis.) Next, try breaking up the scale segment from Figure 2 into even smaller chunks of, say, three or four notes, to come up with your own rhythmic and/or melodic motifs. Remember, keeping things simple can help you stay creative.

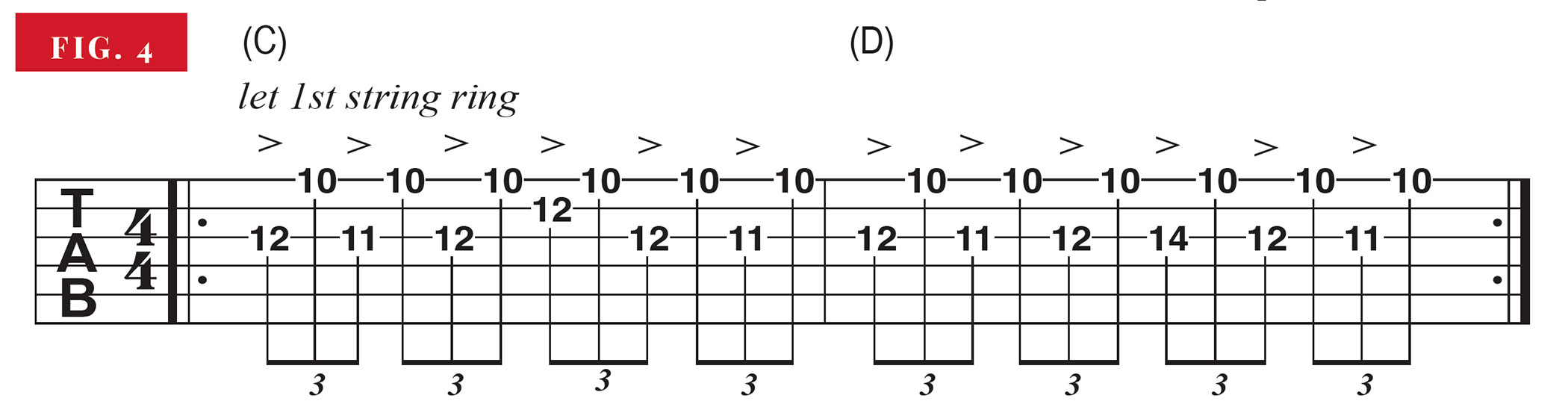

Inspired by Trey’s line at 6:41 in the aforementioned live solo, Figure 4 exemplifies his remarkable talent for creating dynamic solo ideas over a two-chord vamp. Two of the guitarist’s biggest influences, Jerry Garcia and Frank Zappa, would often go on long solo excursions over this type of limited progression, and at times even just over a one-chord vamp or droning bass note.

The challenge here is to find unique and interesting ideas to keep both you and your audience interested.

As in the previous example, using accents is key, and they’re used here to create an unexpected grouping of notes. Instead of playing eighth-note triplets “normally,” as groups of three notes, here they’re divided into two-note groupings by adding accents and a down-up-down-up melodic contour.

The reiterated high D note on the 1st string functions as a melodic drone. This creates a new tension over the same ol’ chords, giving Anastasio’s solo new life, while also inspiring his bandmates. (More drones to come.)

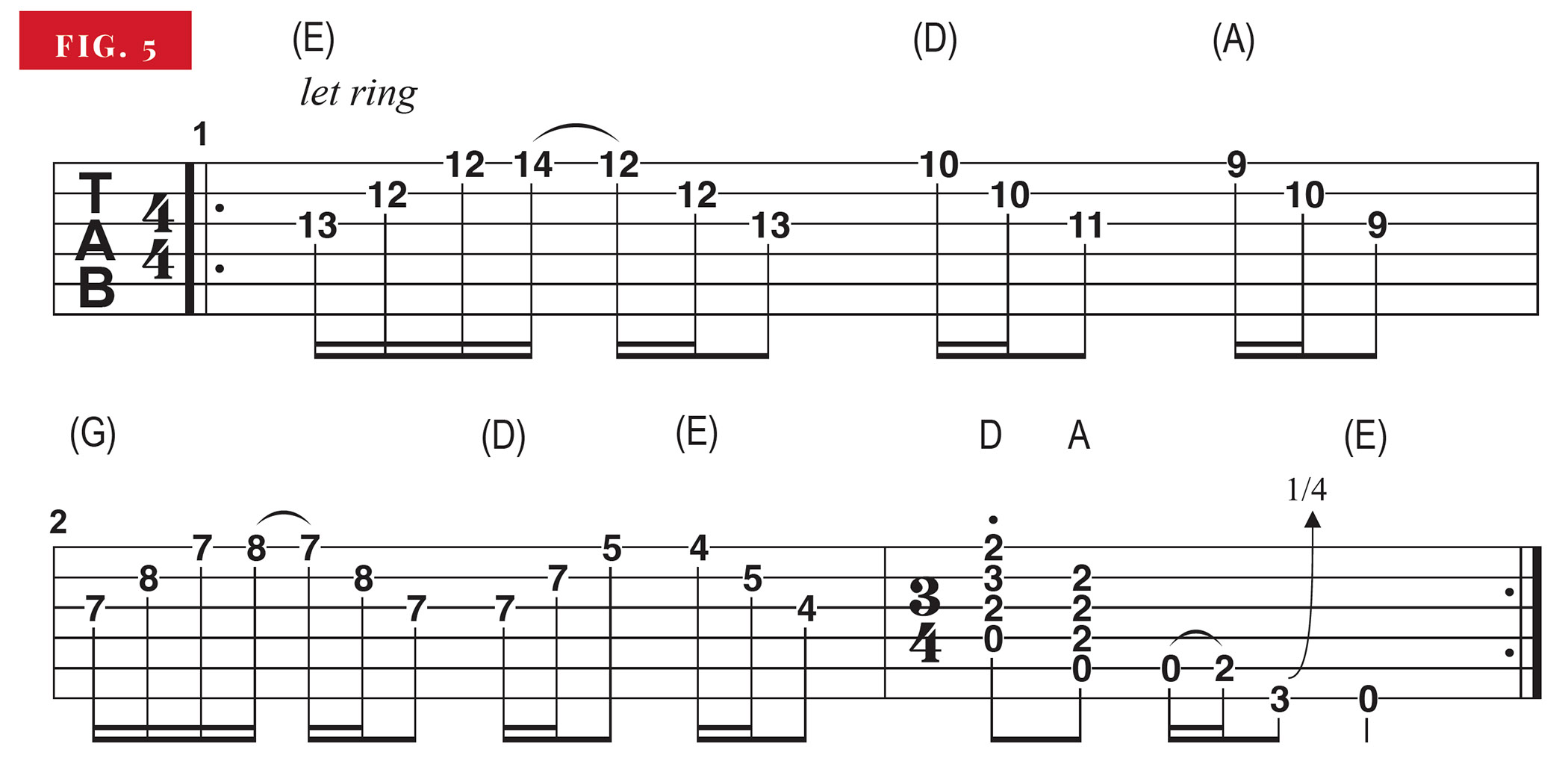

Anastasio also uses rhythm-based ideas to create drama in his songwriting. Figure 5 brings to mind the chorus of Free from Phish’s 1996 album Billy Breathes. (Note that the instruments are tuned down a half step on the record, but our example is in standard tuning.)

Notice how, in 4/4 time, an unexpected three-bar phrase is created, where ones spanning two or four bars are more common and expected. To practice what we preached, we’ve added our own element here by shortening the third bar by one beat, creating a bar of 3/4, which helps to keep the phrase’s momentum rolling into the repeat.

The main takeaway here is that the prog rock-inspired elements in Anastasio’s songwriting aren’t forced; in Free, the music just feels light and fun, which is part of the guitarist’s musical charm.

At its core, Phish is essentially a live band. They have released a plethora of live albums, replete with hours of Anastasio’s soaring lead work; you can almost literally drop the needle anywhere and find a gem.

One such solo can be found in Divided Sky from Phish: 1/2/2016 Madison Square Garden, New York, NY. The guitarist digs into his deep stylistic bag and pulls out some fantastic country and jazz-tinged lines.

Figure 6 is a longer solo chunk reminiscent of his playing in the closing four minutes of this 16-minute epic. Trey’s phrasing often has shades of Garcia, with extended eighth-note major pentatonic-based lines incorporating few bends (you won’t find any here).

As the guitarist’s songs often do, the example navigates chord changes that require moving between keys. The first four bars are in D Mixolydian, followed by D natural minor (D, E, F, G, A, Bb, C) for the Bb chord, and, finally, D major (D, E, F#, G, A, B, C#) for the phrase over the A chord, the V (“five”) chord of D major.

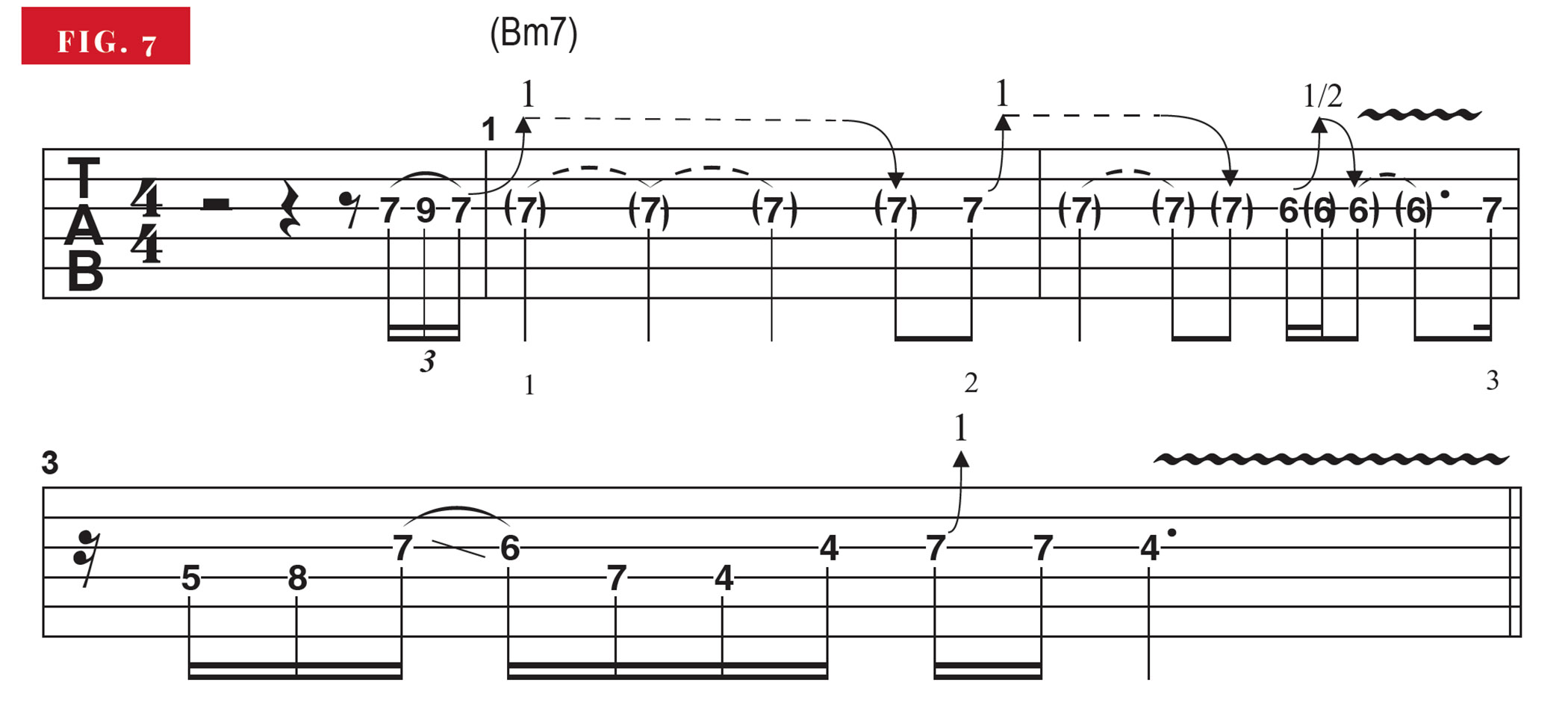

Anastasio’s aforementioned side project, TAB, has had numerous lineups since its inception in 1998; the current version, known as Classic TAB, was formed in 2007. TAB’s November 9, 2022, version of Everything’s Right (see above) features another element of the guitarist’s soloing style, with roots in jazz.

Figure 7 is reminiscent of Trey’s playing at around 9:00, and this time, there’s a healthy dose of bending involved. Over a funky Bm7 vamp, he targets the notes of a minor 7 chord a 5th (two and one half-steps) above, which here is F#m7 (F#, A, C#, E).

This provides access to some extensions (chord tones above the 7th), relative to the foundational B minor tonal center, namely the 9th (C#) and 11th (E). To perform the gradual, almost moaning, bend releases, think of the notated rhythm as just an approximation; allow the bends to release freely, reaching their destination just slightly before the subsequent note is sounded.

A chromatic element (playing notes that are out of key) is introduced in bar 3, as an F#m triad (F#, A, C#) is approached from a half step and one fret above, with a Gm triad (G, Bb D), which provides a moment of heightened tension. (Note the suggested fret-hand fingerings beneath the tab.)

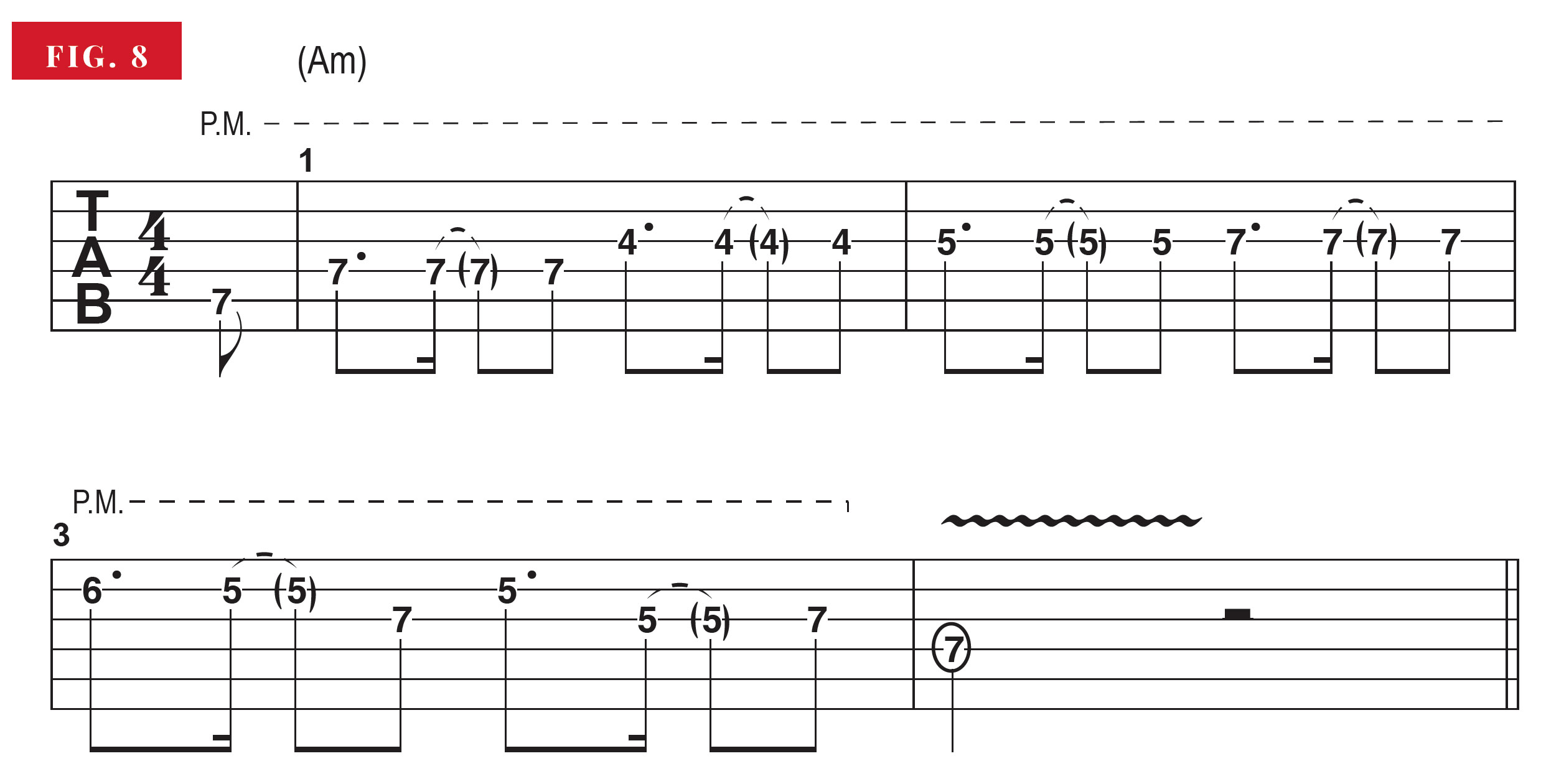

First Tube, from 2019’s TAB at the Fox Theater, has Anastasio providing another kind of rhythmic tension over a static background. The instrumental’s theme (0:45), played over a groove based on the A natural minor scale (A, B, C, D, E, F, G), is pretty straightforward, except for the fact that the guitarist plays it behind the beat, meaning just a tad “late,” or “lazy.”

Figure 8 is inspired by this melody; as you play it, imagine you’re having a rhythmic tug-of-war with the band, dragging just a hair behind them. Keep in mind, this takes some practice to feel natural.

While you’ll most often see Anastasio holding one of his hollow-body electrics made by former Phish soundman Paul Languedoc, the guitarist is equally adept on acoustic guitar. (His collection contains a few vintage Martins, including an 000-28 model from 1933.)

So, let’s finish up by taking a look at some of the creative axman’s acoustic work, like the main guitar figure in Fluffhead, from Phish’s 1989 debut Junta, which brings to mind some of Yes guitarist Steve Howe’s stellar acoustic writing and playing.

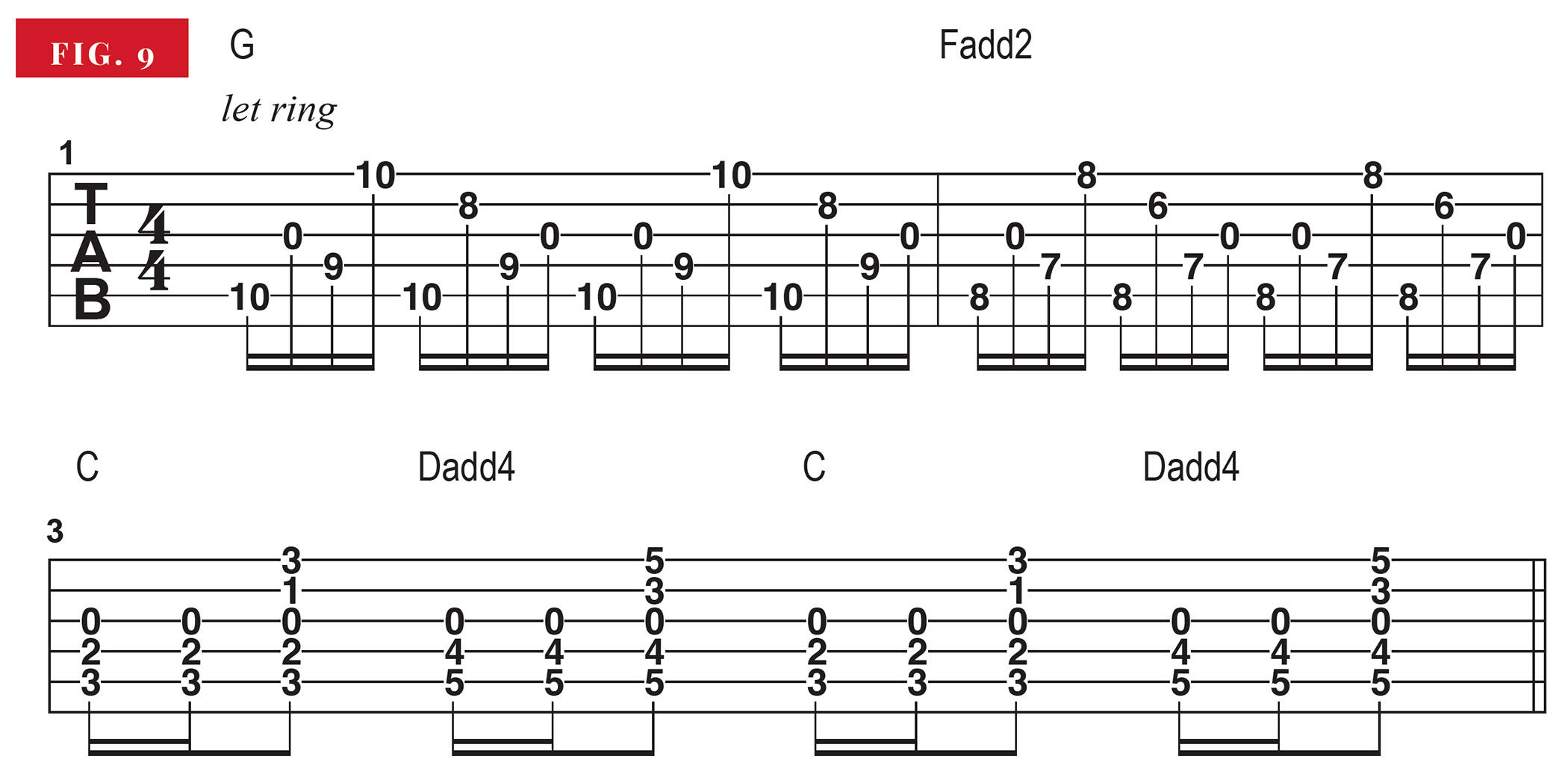

Figure 9 is along the same lines, and here again, simple wins the day, as the same basic open-C chord shape is moved around the neck, allowing for the open G string, nested between the fretted notes, to serve as a drone, creating various tensions in the new chords.

Bar 1 begins with this chord form in the 8th position, creating a jangly G chord, which is then moved down two frets in bar 2 to form an Fadd2 (F, G, A, C), with the open G note acting as the added 2nd. The same note lends a similar tension in the last bar, functioning as the added 4th in the Dadd4 chord (D, F#, G, A).

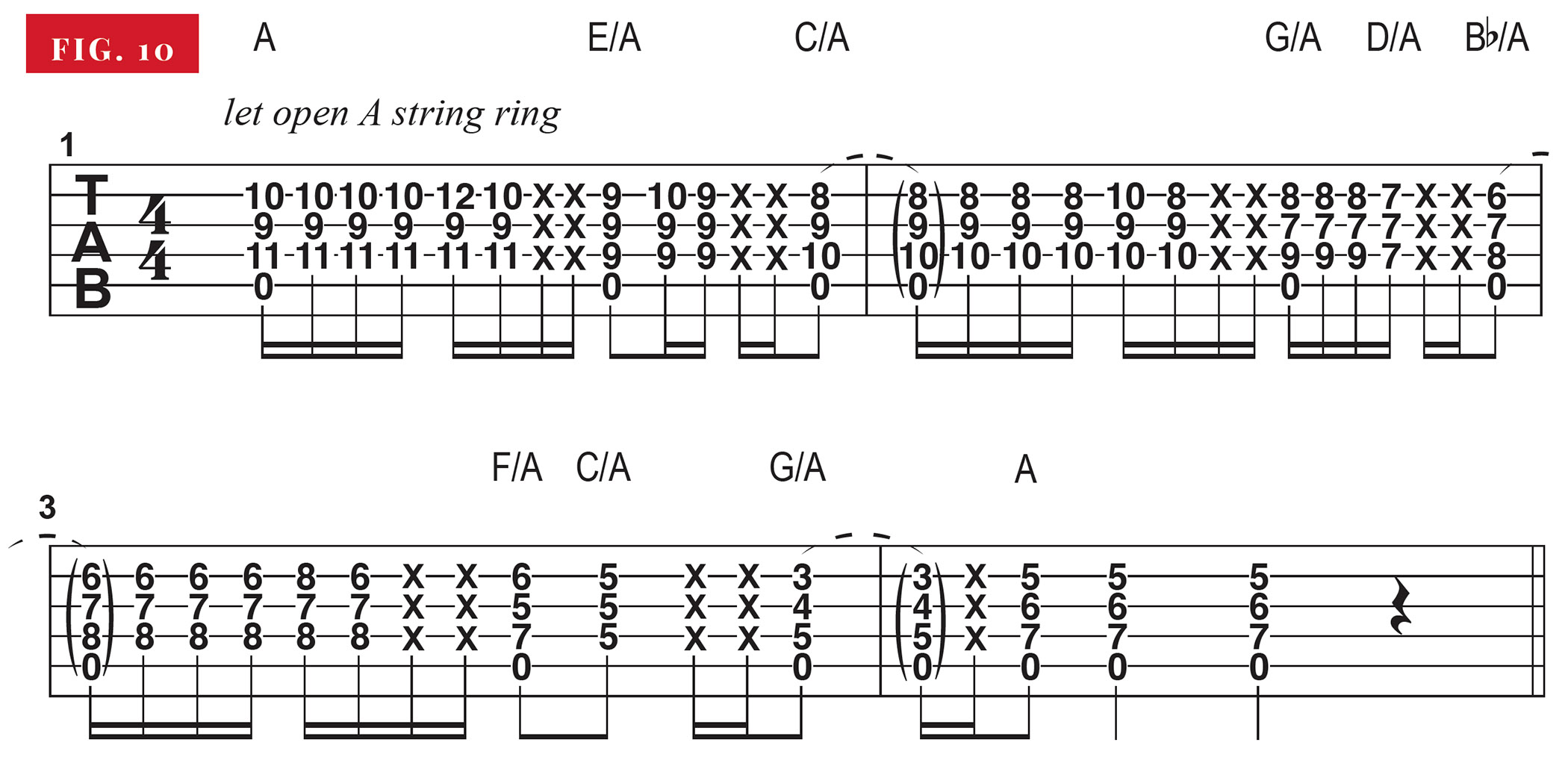

Another example of Anastasio employing a drone, this time with some clever chordal movement, can be found in Sample in a Jar, from Phish’s 1994 release Hoist. Figure 10 brings the intro to mind and involves an open A-string drone below a sea of shifting chord forms.

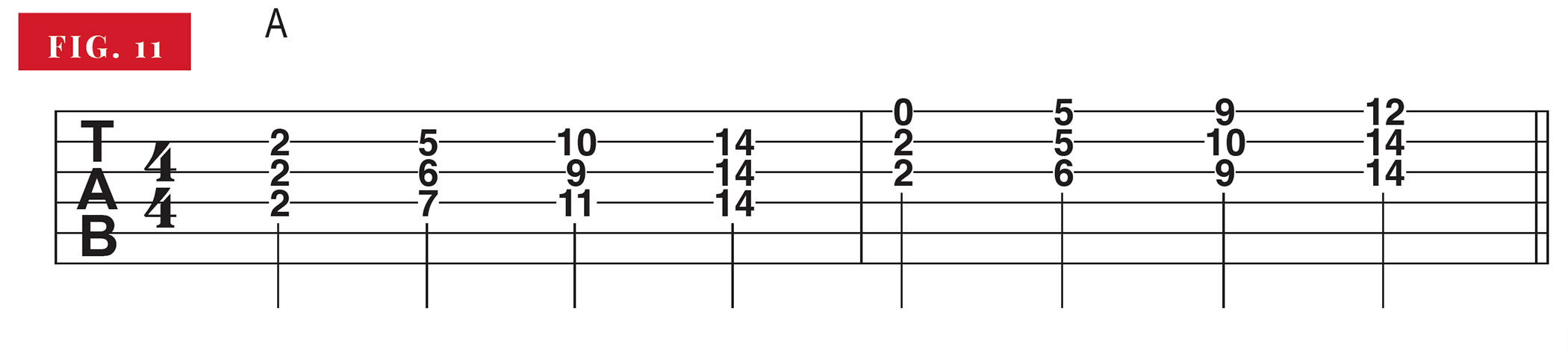

Anastasio is clearly aware of triads and their inversions (chords where the root is not the bottom note) up the neck, the shapes of which are shown for an A major triad on two sets of strings in Figure 11.

There are just three shapes to learn on each string set (strings 2-4 and 1-3), with the last shape in each bar being identical to the first, only 12 frets and one octave higher. Notice how Figure 10 shifts between the parallel keys of A major and A minor, with a nifty b2 chord (Bb/A) borrowed from the A Phrygian mode (A, Bb, C, D, E, F, G) at the end of bar 2.

The overall sound is reminiscent of something Jimmy Page would write, the Led Zeppelin guitarist being another one of Trey’s big influences. These shapes are not only helpful in rhythm playing; they can give your soloing new life as well.

Take another look at Figure 1 to revisit how Trey constructs the opening pick-up motif around a C triad shape, then try using the shapes in your own solos.

Anastasio stands on the shoulders of the great guitarists who influenced and inspired him, employing some similar approaches while following his own creative vision and ultimately arriving at his own signature style. We can take inspiration not only from his playing, but from his spirit of adventure, as he takes his long solo flights, not always sure of just where he’ll land.