Mott The Hoople hadn’t even played a gig when they recorded their debut album shortly after madcap visionary producer Guy Stevens put them together, looking to create his dream collision between the Rolling Stones and electric Bob Dylan.

Although the latter’s influence on their formation period can’t be denied, Mott’s own infernal alchemy started brewing from first rehearsals, hatched into an elemental monster in the studio which sprouted huge, beating wings when they took it live.

At first the new band, then workingly-titled Savage Rose & Fixable, seemed like a marriage made in hell. Stevens’ mental chess game had placed struggling songwriter Ian Hunter Patterson – who’d reluctantly bluffed through his audition at Denmark Street’s Regent Sound Studios, sporting a brown corduroy suit and singing Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone – with a gaggle of younger Herefordshire country boys who’d been treading the UK’s boards as Silence, but piqued Guy’s interest with their attitude. At that time they announced themselves as guitarist Mick Ralphs, organist Terry Allen, bassist Pete Watts and drummer Terry Griffin.

“Guy liked Ian the minute he walked in, because he had that charisma and the shades,” recalls Ralphs. “He didn’t care what he played or sounded like, he looked right.”

Stevens was the driven rock and soul evangelist who had soundtracked the R&B boom (DJing at Soho’s Scene club), created Procol Harum and was now Island Records’ livewire A&R dynamo. He uncannily envisioned something uniquely spectacular erupting out of the band’s unlikely chemistry, including Hunter’s potential as a stellar songwriter and street-savvy rock’n’roll star.

“It was in there waiting but it wouldn’t have come out if Guy hadn’t brought it out,” Hunter says. “Everybody has their hopes and dreams, but they’re buried by being told you’re crap. He was the first person who took a blind bit of interest in me and and built my confidence up. If it hadn’t been for him seeing that glimmer of whatever I wasn’t aware of, I’d still be working in the factory. I found it very flattering that he would put all this effort in to make me feel better. Usually people put this effort in to make themselves look better.”

Stevens would have fronted the band himself but, as Hunter says, “he couldn’t sing and was incensed because he couldn’t play anything. We were working through him.” But if Hunter started as Stevens’s vehicle he soon started showing an aptitude and determination for writing songs for the new band; perhaps initially ingrained by working for a London songwriting firm.

From the first of eleven days rehearsing at the Pied Bull in Islington, Hunter would get there early, writing on the piano, drawing with bared-soul poetic vision from hard life experiences, overcoming a divide between seasoned city pro and younger country boys. “I’d had forty-four jobs. I knew this was my one and only shot,” reasons Hunter.

Early compositions such as the racism-savaging Road To Birmingham and The Times They Are A-Changin’ soundalike If The World Saluted You (later retitled Backsliding Fearlessly) were transformed when the band pumped them with latent elemental power that seemed to course from their loins like a giant electrified snake. The epic Half Moon Bay reached a peak aboard its mighty riff, Hunter singing with authoritative control before the Moonlight Sonata-organ-abusing helicopter attack heralded another behemoth climax.

This merciless approach to the dominant ballads also erupted when Stevens suggested covering Doug Sahm’s lonesome ballad At The Crossroads from 1969’s Mendocino set and Sonny Bono’s Laugh At Me, along with the band’s idea to tackle the Kinks’ You Really Got Me after spotting its creators arriving at Pye Studios. After trying vocal versions, the song swelled into the riotous ten-minute instrumental that would soon spark live mayhem, but was edited into two tracks for the album. “We played it very fast, very high energy; very uncool for those days,” said drummer Griffin. Instrumental Rabbit Foot And Toby Time provided another rocker.

Recording took two and a half weeks at Morgan Studios in north-west London, where the band experienced Stevens’s manic coaching; gurning, hurling chairs and gesticulating wildly as he delivered incendiary rants and fired the band to greater heights of energy and performance.

The band still needed a name. Ruling out Brain Haulage and Ball & Chain, Stevens remembered a blackly humorous novel by Willard Manus he’d read in Wormwood Scrubs while incarcerated for drugs offences in 1968. It concerned an eccentric ‘Hoople’ (US slang for loser) called Norman Mott, who didn’t fit into society so sailed away in a hot air balloon to find himself “two miles from heaven” (Manus later said he got the character from a bum called Major Hoople in a comic strip). Stevens had been holding the name back after the junkie inmate who lent it to him died, so Mott The Hoople were christened and the album’s first acetate mailed to selected tastemakers.

The world first heard about Mott The Hoople in Pete Frame’s then-recently established ZigZag magazine. September’s issue boasted his interview with Stevens, covering an amazing story that started with him being president of the Chuck Berry fan club and ended with Mott The Hoople. Stevens gleefully acknowledged the Dylan influence, making it sound like a mission as he enthused: “The record is amazingly like Dylan in places, simply because Dylan is like, in the sky to them. They are completely and utterly on their backs about Dylan. We’re having a picture of Dylan inside the sleeve, because it’s all about Bob Dylan. But, at the same time, they have a thing of their own. We’re calling the album Talking Bear Mountain Picnic Disaster Dylan Blues.”

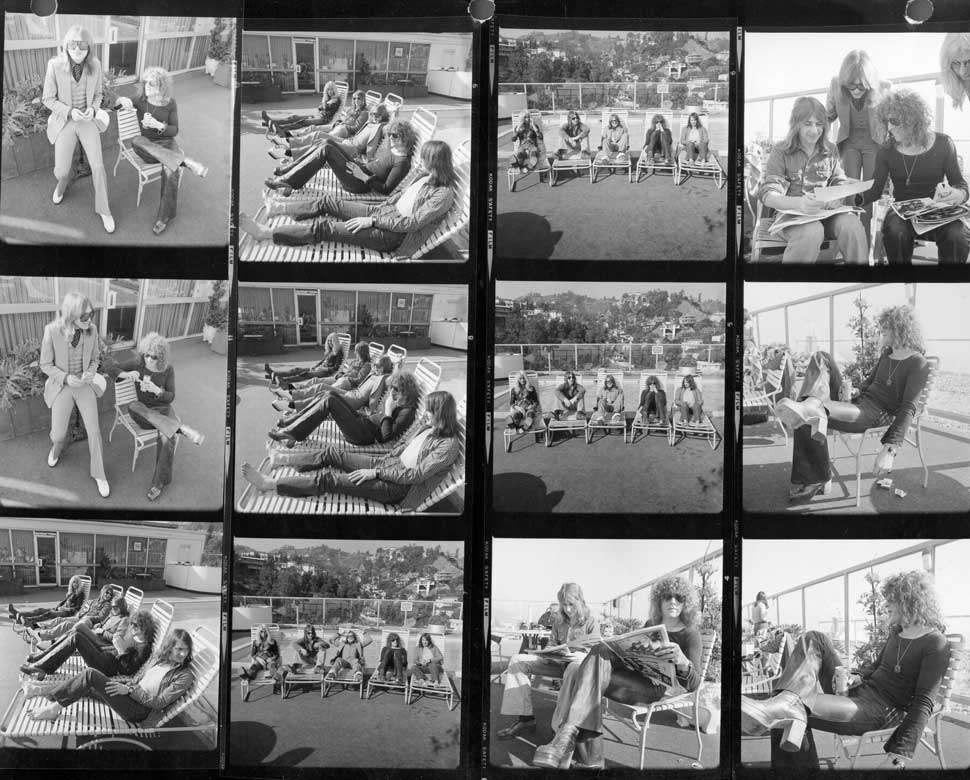

Describing the album as “staggering”, Frame becomes Mott’s first and most vociferous press champion, insisting on putting a centrefold photo of Mott in that issue (Stevens took Hunter’s place as he missed his bus to the session!).

“Guy was just a complete mad-ass rock‘n’roll maniac,” recalls Frame. “He was a raving, raving loony, the sort of guy you hung around with for five minutes and were just in thrall with his enthusiasm. We hit it off immediately. Island Records was the coolest label by far at that time. Guy sent me a test pressing of the first Mott album before I’d ever heard of them. I was just completely blown away. Before we’d often talked about the great sound of juxtaposed organ and piano in the same band. Procol Harum did it, and Guy formed them too.”

The test pressing would not end up the finished release, after Stevens decided it was too heavy with ballads and demanded another rocker. Ralphs quickly wrote the dirty chugging road anthem Rock And Roll Queen, its grainy swagger dunked in dense Beggars Banquet-style sound. The lyrics were to the point: ‘She’s just a rock’n’roll queen, you know what I mean/And I’m just a rock’n’roll star’. Released as the first single in November (Road To Birmingham the non-album B-side), it struck as a much-needed call-to-arms for rock – as Anarchy In The UK would for punk several years later.

The first time Mott The Hoople was heard by the outside world was when At The Crossroads appeared on Island’s Nice Enough To Eat budget-sampler alongside King Crimson, Free, Jethro Tull, Traffic, Fairport Convention, Spooky Tooth and bonkers Stevens side-project Heavy Jelly. It boded well for the album as its Stones ballad-style guitar curled around Allen’s rich organ, Watts’s bass teasing with the monolithic riff that would ignite one of the climactic home-stretch codas that elevated Mott’s ballads; relentless and majestic, topped with Hunter’s spontaneous vocal outcries.

There was already something tantalisingly different about this band, on the surface marking the arrival of Ian Hunter but never forgetting the band pushing him, underpinned by the volcanic rhythm section of recently deceased Overend Watts and Buffin.

Housed in a sleeve based on Maurits Escher’s 1943 lithograph Reptiles and now titled Mott The Hoople (after ruling out The Twilight Of Pain Through Doubt, from an Italian album unearthed by Ralphs), the album unveiled the new monikers Guy had designated for the group; Ian lost Patterson in favour of his middle name Hunter, Terry Allen gained his middle name to become Verden, Terry Griffin arrived at Buffin from a childhood, Watts-awarded nickname, and Watts’ middle name Overend was moved forward.

The album was met with lukewarm reviews from the conservative music press but enthusiasm from underground publications like International Times, which declared: “They have brought a tenuous (and probably transitory) sophistication to rock and roll and in doing so have transcended the acid/progressive rock of the late 60s and become the only rock and roll band of the 70s currently around… I find what traits of Dylan there are in Mott The Hoople’s music pleasantly nostalgic. It’s like my favourite bits of Dylan have been cut out and preserved in a thick, spicy sauce.”

Mott didn’t have to care about critics when their album got positive responses from Roger McGuinn and Bob Dylan himself. During Mott’s first US tour in 1970, Hunter was standing outside a New York club when a figure walked inside singing At The Crossroads. “I thought he was taking the piss,” thought Hunter. When the pair’s eyes met again inside the club, Hunter recognized Dylan. “He said: ‘Mott The Hoople!’, then started jumping up and down, singing At The Crossroads, and he’s got all the lyrics. I went to see Bob all through the 70s; the first time I ever got to see him. I was blown away. I’ve been very much into Bob since. He’s just the main man for me now and always will be.”

Mott The Hoople now sounds like an ethereal, occasionally unhinged distillation of everything that was great about heady, revolutionary ’69, soaked in those key influences but flying the deeper spirit that would blanket upcoming albums like Mad Shadows and Brain Capers.

Soon Mott would become the UK’s wildest live rock’n’roll act, forging templates for glam and punk during their short-lived reign as 70s chart stars before buckling under their internal frictions – and later becoming a beloved heritage act with Hunter long acknowledged as one of the UK’s greatest singer-songwriters. This earliest model was a more dangerous beast, swimming against prevailing musical tides to ignite its own, through widescreen rock’n’roll fantasy and self-harming honesty, extra edge coming from being the closest the world got to a Guy Stevens brain-scan, with all the scary carnage that entailed.

Glowering from the vaults like an old testament scroll, Mott The Hoople still entrances as their first, eccentrically-tinted but lustrously garnished battle cry, showing a band pilfering from rock’s existing blueprints before giving the world equally-resonant ones of their own. We were so lucky to have had them.