When loving mother-of-two Allison Salter was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) in June 2022, she resolved to die on her own terms.

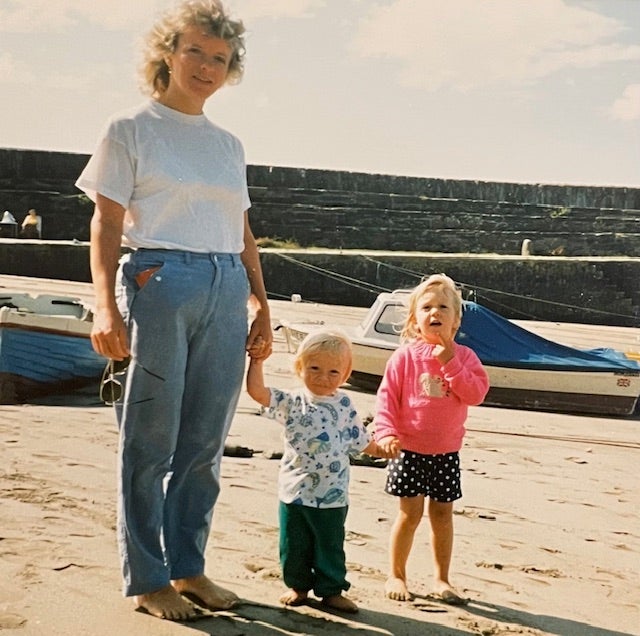

Described by her daughter, Catie, as a passionate, sociable, and independent woman, the disease gradually stripped Allison of her ability to do the things she loved most.

In February 2023, with all treatment avenues exhausted, she turned to assisted dying. While her death at Dignitas in Switzerland ended her suffering, it left Catie emotionally torn and bereft.

Though relieved that her mother was no longer in pain and grateful to have “memories of her still being the mum I knew,” Catie felt robbed of a natural grieving process due to the legal circumstances surrounding her death.

She was unable to travel to Switzerland to be with her mother in her final moments, forced instead to say goodbye over a video call while hiding the truth from friends and colleagues. In the weeks that followed, the family’s grief was overshadowed by fears of being arrested for assisting in her death.

Catie believes that legislation to legalise assisted dying—set to be debated in the Commons on Friday—would spare families like hers from the additional pain of navigating such a difficult process abroad. “If this law had existed, Mum could have died at home, surrounded by the people who loved her,” she says.

A heartbreaking diagnosis

Allison first began to notice symptoms of MND in 2021, when she started to lose control of her legs. Initially thought to be a mechanical issue, it became clear something was seriously wrong as the problem spread to other parts of her body.

As months passed, Catie watched her mother lose the ability to do the things she loved most. Allison’s cherished long weekend walks with her husband became impossible as she lost the ability to walk completely. When her hands began to fail, she could no longer write or enjoy her favourite crossword and sudoku puzzles.

The symptoms worsened, and one day Allison lost the ability to sing. “She had a beautiful voice and loved to sing,” said Catie, 36. “One day I said to Mum, ‘Sing along,’ and she looked at me and said, ‘I can’t.’ It was a really sad moment.”

In the final weeks before her death, Allison could no longer speak. Her heartbreaking decline culminated in her losing control over the muscles in her throat, leaving her choking on food.

By the time she was diagnosed in 2022, Allison knew this was not how she wanted to live the rest of her life. She penned a letter outlining her wishes to pursue assisted dying before she lost the ability to write.

“When she realised what it likely was in May 2022,” Catie said, “she told Dad that she wasn’t going to see it through to the end. In her letter, she made it clear that it was her choice—and only her choice.”

“When she told me I was shocked but not surprised. I wasn’t surprised because of who she was - it totally made sense because of how independent she was. It made total sense she didn’t want to be in bed at the end unable to do anything.”

The journey to Dignitas

After months of secret planning, February 2023 marked the time for Allison to travel to Switzerland.

Catie’s father accompanied her, while Catie and her sister stayed behind, saying their goodbyes on a chilly February morning as Allison left for the airport.

In her final moments, the sisters FaceTimed their mother. Later, they learned of her passing through a four-word text: “She sleeps, so brave.”

Though her death was peaceful, the family’s ordeal was far from over. The UK’s legal stance on assisted dying cast a shadow over their grief, forcing them to navigate legal fears amid mourning.

“The time leading up to her departure was incredibly difficult for us,” Catie recalled. “The amount of planning and secrecy involved was enormous. We couldn’t tell anyone—not even Mum’s closest friends. When the date came, I had to go to work as if everything was normal.

“It was heartbreaking seeing people visit Mum, knowing it would be the last time they’d see her, but they didn’t know. So many people have said that, had they known, they would have spent more time with her, visited more often, or even wanted to accompany her to Switzerland.

“When we told them afterward, it felt like we’d lied and deceived people who cared deeply about her.”

What is the current UK law?

Under current UK law, assisting someone in dying carries a maximum prison sentence of 14 years.

For Catie’s family, this legal barrier turned the months following her mother’s death into a time of fear rather than healing. They were consumed by anxiety that their father could face arrest simply for being by Allison’s side as she passed.

“Mum should have been able to die in the UK,” Catie said. “It would have spared our family weeks and months of stress, worry, and ongoing trauma. It’s very hard to grieve when you’re scared.

“We couldn’t even have simple things, like a funeral, because that would mean people asking how she died.

“If the law were changed, loved ones could be by the patient’s side without fear. There would be no sense of deceit, no fear of the police knocking on your door. And after the person has gone, you could grieve properly.”

How could the Assisted Dying bill change this and what are the concerns?

Labour backbencher Kim Leadbeater’s Bill to legalise assisted dying will come before the Commons on Friday, marking the first debate and vote on the issue since 2015.

The proposed legislation, which applies to England and Wales, would allow terminally ill adults with less than six months to live and a settled wish to die to seek assisted death. However, its passage remains uncertain, with MPs granted a free vote and the Cabinet divided on the issue.

Opponents have raised concerns over potential coercion, so-called “mission creep,” and what they see as rushed legislation.

Addressing these fears, Catie said: “I understand the concerns, but I’ve met with Kim, and she has thought through every single detail. The Bill is strict. If the process is anything like what my mum went through, coercion would be picked up. This law would introduce even more safeguards than ever before.

“There’s a misconception that this is an either-or with palliative care—but that’s not the case. The campaign supports making palliative care as good as possible so people have a balanced choice. For me, though, I’d prefer the assisted dying route.

“This is about adding to a care plan, not replacing it. It’s about having the choice.”