Wildlife photography is considered one of the most challenging genres, and not only from a technical point of view. It requires extensive research, long-distance travel to often remote locations and the ability to adapt to different climates. Most importantly, it also means taking adequate safety measures when tracking down the animals. Capturing the essence of wild creatures and conveying a sense of proximity in one frame is what brings exotic wildlife close to the viewer. This can only be achieved by respecting your subjects’ boundaries. However, this brings many challenges.

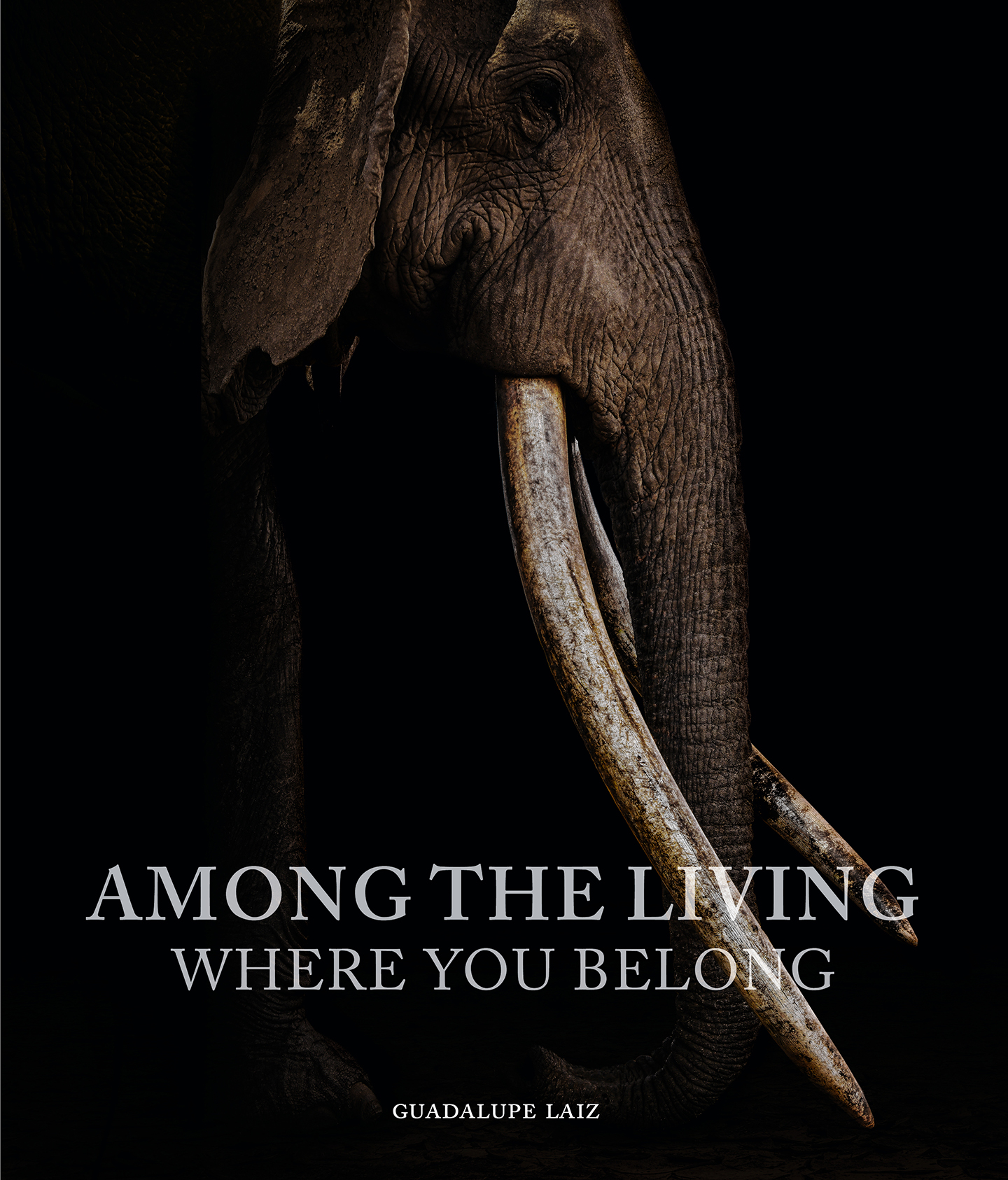

Guadalupe Laiz has spent six years travelling across Africa capturing stunning images of wildlife for her book Among the Living: Where You Belong. The book, published by The Images Publishing Group, features 429 images of rare and impressive wildlife, including Big Craig, the biggest tusker elephant in Kenya, and the famous Susa gorilla family in Rwanda. Among the Living is available now, priced £100/$125.

Argentinian wildlife photographer Guadalupe Laiz aims to strike a balance between getting close enough to shoot the perfect image and respect for the animals she works with. She spends months in the wildlife’s natural habitat, allowing her to take the viewer on an intense journey that not only reveals the beauty of these animals but also the difficulties they face in the modern world.

Guadalupe is passionate about educating and partnering with non-profit organisations. While raising awareness, she worked on her latest publication ‘Among the Living’. In our conversation, she explains how she unexpectedly became an award-winning wildlife photographer and, more recently, an educator.

Interview

Hey Guadalupe, what motivated you to pursue a career in wildlife photography?

To be honest, the wildlife chose me rather than the other way around. It wasn’t a conscious decision; it just happened. I was in commercial and editorial work in fashion, very different from the work I do now. My introduction to wildlife photography wasn’t with wildlife, it was through the Icelandic horses. Although they aren’t wild, they do have a wild side to them. Whenever you see a horse in Iceland, it won’t be like any other farm that has horses. They roam freely in the stunning Icelandic landscapes. Initially, I travelled to Iceland to shoot those landscapes but on my first day,

I came across the horses.

It was an instinctive decision to follow that path and from there, I got curious about what it would be like to photograph other animals. That’s how I ended up going to Africa and discovering all the wildlife that the continent has to offer.

Your projects often extend over long periods of time, how do you go about establishing relationships with the local communities and the people who share the animals’ habitat while you’re there?

No matter how many times you visit Africa, you are always a visitor, unless you move and start your life there, so it’s crucial to be respectful to the locals as it’s their home. While I was in Iceland, I took my time and got to know the farmers, living with them for a while, like two or three months at a time. I got to know them and their lives, which also helped me to understand the relationship they have with the animals. I did the same thing in Africa, where I got to know the people first, built relationships, met their families and learned about their lives.

They are the ones who know the animals better than anyone else. They take me off the beaten path and do things a little bit differently than tourists would. And, importantly, they respect the animals. I refuse to work with anyone who makes animals nervous or gets in their way. I need to collaborate with people who share my values. I want to get involved with and support conservation projects, for example. That is not only valuable work but it also shows my appreciation towards the locals.

Tell us more about the Umubano gorilla family that’s featured in your latest book...

The Umubano family holds a special place in my heart. It’s a family group of 13 members living in Rwanda and they were the first family I visited. I was lucky to be able to do so, thanks to the people and relationships I built there.

When I photographed the family, I decided to go by myself, instead of being part of a group, so that I could move slowly around the gorillas. A guide was there to ensure my safety because Silverbacks can get very territorial. When I am in situations like this, I stay focused on doing the best I can. It was an incredible experience, and sometimes I feel like I haven’t had enough time to process how lucky I am to be in situations like this. After photographing gorillas over and over again, I realised that I had become attached to them. They are so similar to humans.

Among the Living took six years to come together. What were the things you most enjoyed about this project?

I have an obsession with proximity. I don’t like using camera traps, so the best moments are when I have the chance to get close to the more docile wild animals. It was special to see ‘Big Craig’, one of the biggest ‘Big Tuskers’ [elephants with tusks that almost scrape the floor] left in the world. When I met him for the first time in the Amboseli National Park in Kenya, I realised how big he was. He was right in front of me and I could have touched him if I’d reached out my hand – of course, I didn’t though! On another trip, I was sitting next to him all afternoon when he was taking a nap.

Getting that close isn’t easy to achieve but I have a few tricks up my sleeve. For example, when I’m capturing cheetahs preparing for a hunt, they go high and climb to the top of the nearest mountain to survey the area. It’s important to not get in their way during the actual hunt, so I seize the opportunity to capture them when they are observing the area. We were able to get close by positioning ourselves in a car on another mountain nearby. Sometimes, there was a cheetah right in front of us, which was an unforgettable experience.

Over the years, I’ve been able to work with the same guides, so we know each other well and have built up a friendship. They know me well enough to trust that I won’t react poorly in situations like these. I remain calm and move slowly. But any time I can get out of the car, I do. I drag my body around and get full of ticks that may require a visit to the emergency room. But it’s important because you are on another level to document the animals, and you can see that in the photographs.

…and what were the biggest challenges?

It can be very chaotic because when things happen they happen quickly. If you aren’t focused, you’ll miss these moments. Being prepared is key as you have to make decisions as quickly as the action happens. The main thing about working with wildlife is that you think you are as ready as you can be but everything happens differently. Even if you’ve done your research and are in the location at the specific time of the year to see the animal. Working with the best guides and people helps but you still need to improvise 24/7. Things just happen the way they are happening.

I believe the reason there aren’t more wildlife photographers out there is the amount of patience required. It can be really boring and so my approach has always been to pick one animal and stay still until I have it in front of my lens. I don’t move around all day. You just have to trust that the time you spend waiting will eventually reveal a magnificent moment. Sometimes, I’ve spent an entire day, waiting for over eight hours to capture an animal, while hearing about some incredible sightings elsewhere. However, I don’t have FOMO (the fear of missing out). I’m aware other things are happening that could potentially be more interesting… but that’s part of the job. I stay focused and dedicated.

So what type of animals do you usually have to wait a long time for?

Lions – you often have to wait all day until they make an appearance. If I’m shooting in a group, some of the other photographers go back to the lodge if the lions haven’t shown their faces in the morning hours, when the light is best. But I don’t head back, I wait.

Your work includes lots of black-and- white images. Why is that? Do you prefer shooting in monochrome?

I choose to remove the colour from my images because it puts the focus on the animal as the main subject of my photographs. By eliminating the distraction of colourful landscapes in the backgrounds, I can better highlight the individuality and beauty of each animal. In my opinion, black-and-white photography creates a different kind of visual impact that helps draw attention to the subject in a more powerful way.

You mentioned your partnerships with non-profit organisations focusing on environmental issues, such as animal abuse, what’s the benefit of this?

Animal abuse and trafficking are major problems that impact wildlife all around the world, so for me personally, it would be impossible not to partner with organisations like this. It’s a sensitive topic for me and

I tend to get very passionate about it. We could have a 10-hour conversation about this topic if you have the time…

We take so many things for granted, including threatened wildlife, and I think we have forgotten how we actually should see them. Habitat loss is a significant threat and the number of some types of animals left in the world is shockingly low. Society is not going to change from one day to the next and we’re going to continue to advance and take up more and more space with urbanisation and farming. So I’m proud to support non-profit organisations such as ‘Big Life Foundation’ and others.

I worked with scientists together and learned. I try to spread awareness among the people I meet and raise funds for specific projects through silent actions. Here, education is the number one thing for me. We are not giving people new information, the idea is to relearn how we see the animals again intending to change the mindset of people to make clear that we are responsible. Educating people and building a connection to far away wildlife is a huge gap... I think it’s important to gain some perspective, and that is the message in the book. I hope people read the book and reflect on this message.