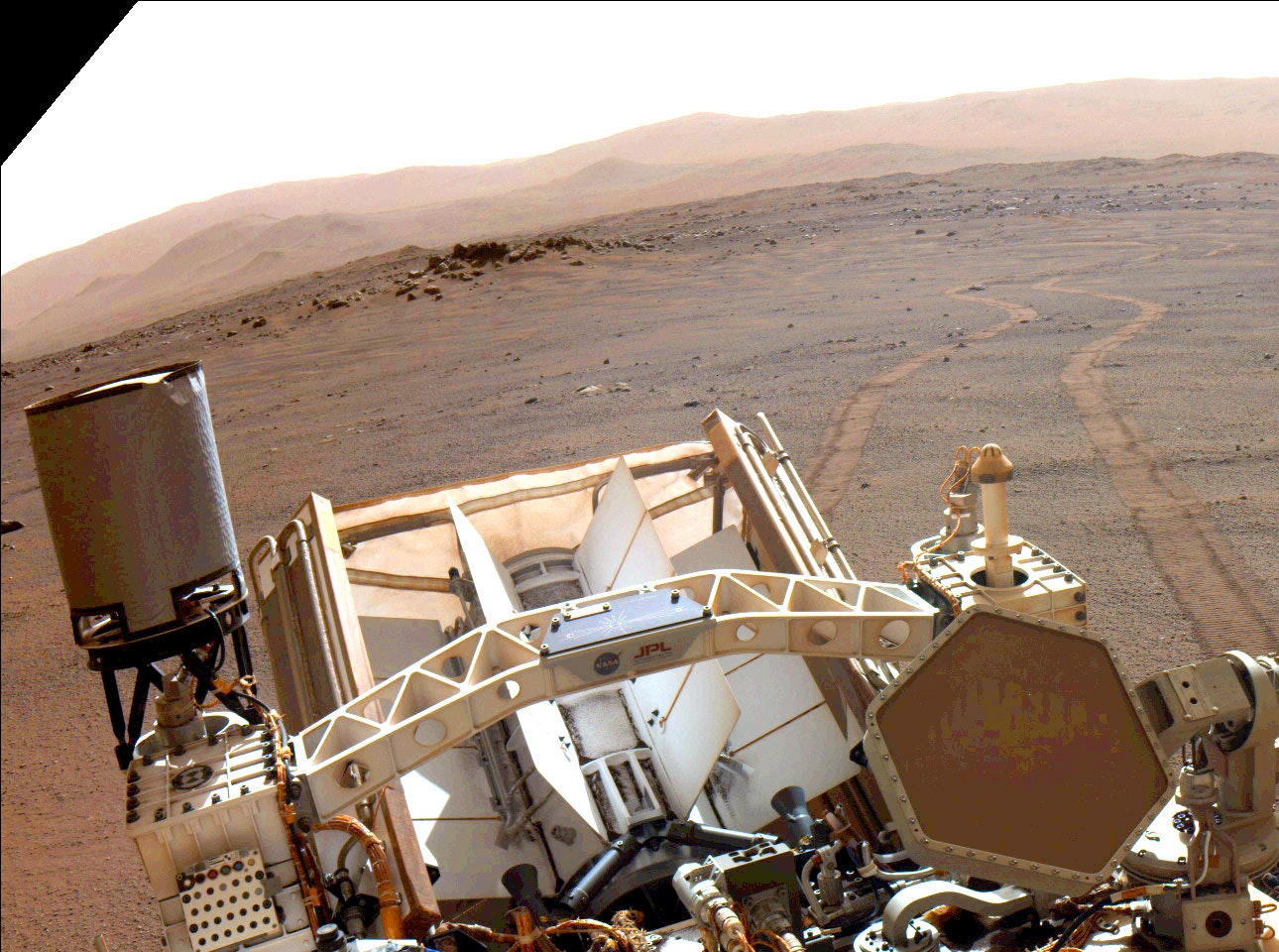

A lunchbox-sized module, which currently sits on Mars in the belly of the Perseverance rover, might hold the future of human exploration on the Red Planet. This device has successfully produced oxygen from the brutal Martian atmosphere, according to a recent article published in the journal Science Advances.

The module, also known as the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE), sends Martian air through a HEPA filter, compresses it, and heats it to 1472 degrees Fahrenheit. MOXIE then uses electric current to split the carbon dioxide-heavy Martian air into oxygen and carbon monoxide.

What’s new — While MOXIE relies on technology that’s been long used on Earth, it was a challenge getting the job done on Mars, where the air is over 100 times thinner than here. The Red Planet’s atmosphere is composed of only 0.16 percent oxygen, compared to 21 percent on Earth.

”You’ve got to show it works on Mars, and that Mars doesn’t have any hidden surprises that we didn’t anticipate,” says principal investigator and Massachusetts Institute of Technology aerospace engineer Jeffrey Hoffman.

It turns out that the method does work, after all. This matters because oxygen production will be critical for a successful Martian mission — both for breathing supply and to lift a rocket off the Red Planet.

In the first year after Perseverance landed on Mars in February 2021, MOXIE did its thing seven times (all successfully) and produced just under 50 grams of oxygen.

In 2022, MOXIE has run for another four cycles, bringing the total to 83 grams of oxygen. This “doesn’t sound like a whole lot,” Hoffman acknowledges. “It’s about what you would get from a small tree.”

Of course, researchers don’t plan to sustain Martian with merely a device around the size of a lunchbox. Future MOXIE-derived systems will be hundreds of times larger and run constantly, producing 2,000 to 3,000 grams of oxygen each hour — as much as a small forest.

Why it matters — Any human mission to the red planet will, of course, need oxygen. But MOXIE isn’t just meant to sustain people.

To return to Earth, spacecraft need fuel and oxygen to lift off. A vehicle that can break out of Martian gravity to return to Earth is going to take “tens of tons of oxygen, much much more than you’d ever need to breathe,” Hoffman says.

But it would be extremely expensive to fly in more fuel and oxygen from Earth. A return from Mars would likely demand on-site oxygen production, since the element makes up about 80 percent of the fuel mass needed for the sort of oxygen-methane propelled spacecraft that could lift off from Mars.

This first-ever successful demonstration of mining and processing materials found on another world also opens up the possibility of brewing other useful materials, like methane, at other above-Earth destinations.

Here’s the background — The idea to manufacture oxygen out of Mars’ abundant carbon dioxide isn’t exactly a new one: We can credit the Planetary Society, a nonprofit space research organization, and the aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin.

In 1996, Zubrin proposed a process that requires “present-day technology, some 19th-century industrial chemistry, and a little bit of moxie.”

Today, MOXIE’s solid oxide electrolysis unit takes advantage of chemistry that is “much more recent and immature,” says Michael Hecht, the mission’s principal investigator at MIT’s Haystack Observatory.

The researchers work with two versions of MOXIE: one that’s perched on Mars and a twin back home at MIT.

This setup lets the team take a closer look at the system, its intricacies, and the degree of stress it can take.

“If something goes wrong, we can put in a replacement part, whereas we have to treat MOXIE on Mars with great care so we don’t damage it,” says Hoffman. “It’s fine-tuning.”

Specifically, it’s important not to produce so much oxygen that the device starts to cover itself in soot, a process known as coking.

Overall, MOXIE is a relatively simple concept, Hecht explains. “Most of the stuff we fly to Mars is pretty primitive — I describe the science experiments as junior high school experiments. But making anything work on another planet is extraordinarily difficult.”

What’s next — Now, the MIT team hopes to break their own oxygen production record — but they need to wait until the next time Perseverance has enough energy to spare for MOXIE.

As the Martian seasons change, the atmosphere nearly doubles in density, and the next scheduled experiment is during the highest density of the year. MOXIE has already run in the highest atmospheric density conditions, and they reach a sustained rate of 9.6 grams of oxygen per hour.

The team also wants to demonstrate that MOXIE works at dusk and dawn, as well as during the day and in the coldest depths of the night (which can reach around 146 degrees below zero).

For the future, the experiment has indicated that the mighty MOXIE could triumph during a future crewed mission — bringing us another step closer to sci-fi Martian settlements.