Many of us love starchy foods like bread and pasta. And there’s a reason for that: Our genes enable us to easily break down these delicious carbs. According to new research, we have possessed this skill for longer than we thought — and we might be even better at it than we realized.

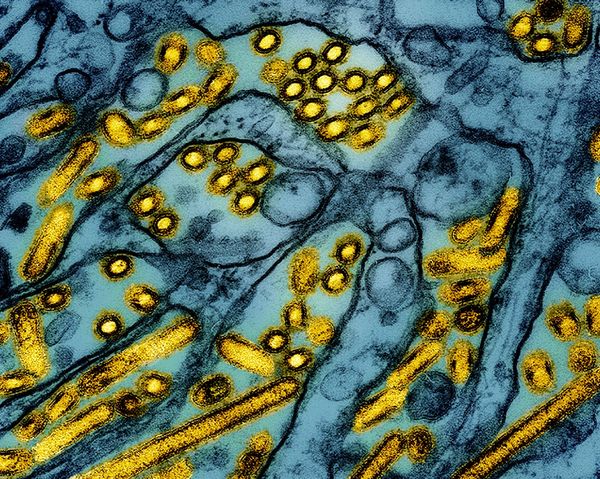

We’re able to digest these complex carbohydrates thanks to two types of genes. One of these genes affects our saliva, allowing starch breakdown to begin as soon as these delicious foods enter our mouth. Crucially, our cells possess multiple copies of this gene, which indicates that over time humans evolved more iterations of it as we came to consume more carbs. Researchers linked this genetic evolution to the advent of agriculture between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago. However, new research suggests this gene’s history of duplication extends even further back.

It’s possible that the duplication of this gene may have occurred as long as 800,000 years ago, according to a new paper published today in the journal Science. The researchers, from the Jackson Laboratory, the University of Buffalo, and the University of Connecticut, analyzed ancient human genomes and reconstructed present-day human genetic regions to understand just when this gene began duplicating and how we came to love starch.

The team took a close look at the human salivary amylase gene, known as AMY1. Specifically, they mapped the amylase gene region in 98 people. Gene mapping allows scientists to identify where genes are located on a chromosome and where copies of that same gene might exist.

They also analyzed 68 ancient human genomes, including a 45,000-year-old sample from Siberia, in order to see whether our archaic counterparts possessed multiple copies of AMY1, too. Indeed, they found that pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers averaged four to seven copies of AMY1 in diploid cells, which are cells with two complete sets of chromosomes. Even analysis of archaic hominin revealed some Neanderthals had duplications of this gene.

“The idea is that the more amylase genes you have, the more amylase you can produce and the more starch you can digest effectively,” the study's corresponding author, Omer Gokcumen, a professor of biological sciences at the University of Buffalo, said in a press release.

While this discovery tells us that duplications of AMY1 in humans and hominins predate agriculture, the team made another compelling finding that reinforces the impact agriculture had on our evolution. By examining the genomes of European farmers, they found a significant increase in AMY1 copy numbers over the last 4,000 years, suggesting that agriculture’s start about 12,000 years ago ultimately influenced genetic development.

Not that you need to justify the urge to feast on bread and pasta, but this paper gives a compelling, scientifically based backstory for when you are craving a fresh baguette.