COAL may have been the lifeblood of Redhead, but the artery carrying it was the rail line slicing through the village's western fringe.

The railway was also a lifeline for the residents of Redhead.

Passenger trains had been stopping at Redhead since 1916, and the platform that remains on the Fernleigh Track had been built in 1925.

According to rail historian Ed Tonks, the platform was once renowned for its gardens, with trees and shrubs arranged in planter boxes.

"When it was a passenger station as such, the staff put a lot of time and effort into their gardens," Ed Tonks says.

The old Redhead platform rises like an island in the middle of the Fernleigh Track. Just as it separates north- and south-bound cyclists and walkers now, this island helped the flow of coal and people to continue in the days of rail.

The island sat between two lots of tracks, the main Belmont Line and a loop.

"It was to enable trains to cross," Ed Tonks says of the island. One train could stay on the main branch line, while another could be diverted onto the loop.

Some coal trains would peel off the line here, heading in to load at Lambton Colliery, which presided over a tract of Redhead land on the sea side of the tracks.

Standing on the island, it is hard to see many signs of the mining past.

The site of the colliery is now populated with houses in an estate with a name that replaces mining with something that sounds more bucolic: Redhead Grange. However, the mining heritage hasn't been entirely scraped off the surface.

From the platform, if you look carefully, you can see bobbing above the sea of tiles and colorbond steel a sturdy metal frame.

That frame is part of a group of historic colliery buildings near the housing estate's entrance.

The preserved buildings are considered very significant, as they are the only structures of their type from the late 19th century still standing in NSW. And they still house industrious blokes; the complex is the home of the Redhead Men's Shed.

You may not be able to gaze far into history from the former rail platform, but there is a fine view nonetheless. I can see undulating heath lands to the south, and over to the south-east, slices of the Tasman Sea and distant headlands shimmer in the gauzy, salt-laced air.

Near the back fence of a fine home is a white gate, near where the rail track would have curved around to the colliery to load the wagons with coal.

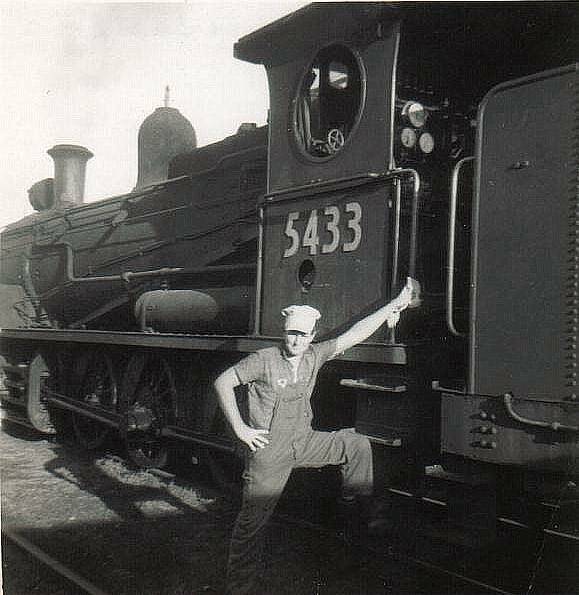

The last train trundled out of Lambton Colliery on December 19, 1991. That marked the cessation of production at the mine. And it was the end of the Belmont Line. It was a moment in Hunter history, for, as Ed Tonks explains, this was the last 19th century colliery locally, and the line was the last 19th century railway built in the area.

As a local television reporter, I was fortunate enough to witness this moment. I had forgotten what the train looked like, until I saw a photo recently. The diesel locomotive was the colour of a summer sunset, a smoky red with a golden band.

What I do remember is the air of melancholy among some of the blokes who were part of that last train journey. I guess it was a heavy load, carrying not just coal but irrevocable change down the line that day.

For so many railway men, this line didn't just represent their livelihood; it was a part of their life.

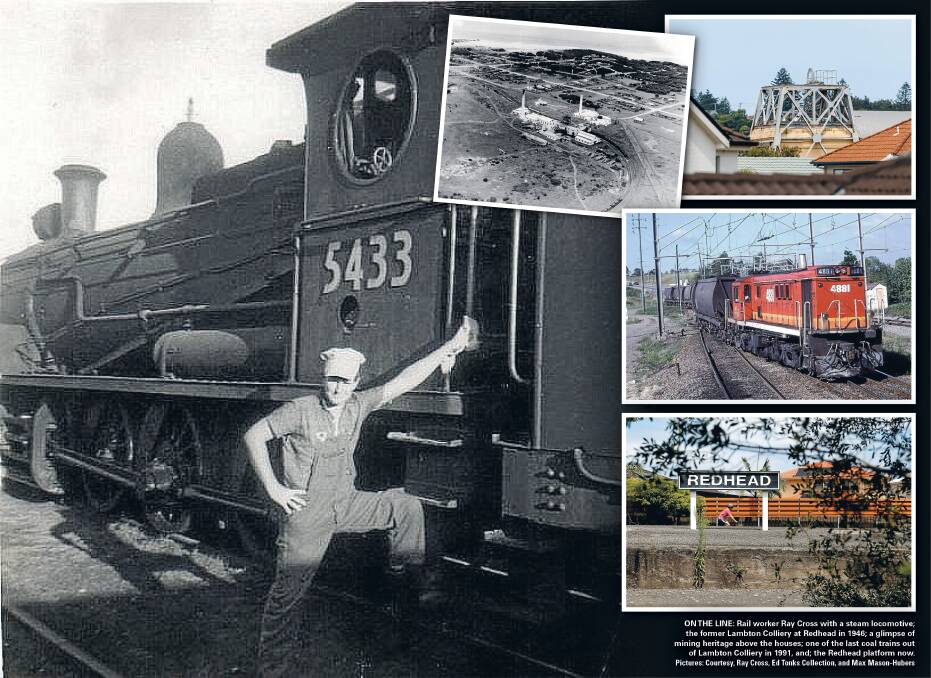

Ray Cross worked on the Belmont Line from 1960, when he was just 17, to 1978.

"I worked out there in steam and diesel days," Ray Cross recalls.

For 18 years, his main job was helping transport coal from the mines along the line for the BHP steelworks.

The run from Lambton Colliery to Adamstown took about 40 minutes, Ray recalls. Not that he's exactly sure.

"I never timed it. Once you got out there, you made your own time."

That included making time to appreciate the environment and even collect wildflowers by the track. Ray remembers picking Christmas bells near Jewells to take home.

"It was pretty relaxed in those days."

For a good deal of Ray's time on the Belmont Line, the passenger service was still operating.

"The 'coalies' would get out of the road for them," he says, explaining they would mostly wait at the collieries for the passenger train to pass.

Time on the line may have been easy-going for Ray, but the climb from Redhead towards Whitebridge wasn't, especially in the days of steam. He recalls the slope was a one-metre climb for every 50 metres travelled horizontally. In other words, it was fairly steep.

"Coming up from John Darling and Lambton [collieries], you'd have an engine at the back, pushing us. He'd push us to Whitebridge."

If there wasn't a "bank engine" to push at the back, Ray explains, the train would take only half a load as far as Dudley Junction, just beyond Whitebridge at the top of the climb (which is still all ahead of me on this journey). Ray and his crew would store the full wagons on a loop there, then they would go back down the hill and grab the other half of the load.

Even when diesel locomotives took over on the line in the late 1970s, there would be two engines pulling, or one at the front and another at the back pushing.

The years may have applied a film of nostalgia over steam trains, but for Ray Cross he was pleased when the diesel locomotives were introduced to the Belmont Line. Diesel was easier, he explains, because "you were out of the weather, and no shovelling [of coal to feed the boilers], but in the steam days you didn't know any different".

Ray Cross moved on from the Belmont Line, and his career would transport him into local railway folklore. He worked on the Richmond Vale line on the Coalfields, driving the last commercial steam trains in Australia. In 1987, when the line looked set to close, Ray was part of a high-profile sit-in. Despite the protest, the line was closed.

Just as he fought for the trains to stay on the Richmond Vale line, Ray wishes the rails had remained here as well: "It's a shame they couldn't use it as a commuter line to Belmont."

Ray Cross has never journeyed along the Fernleigh Track since the rails were removed, but he has taken a look at the old line near Adamstown and Belmont.

"I couldn't believe it,' Ray says. "It was all asphalt. Still, time moves on."

So as I stand on the Redhead platform, I reflect on change. Change to Redhead, to the landscape and community, to industry, and to me. To paraphrase Ray, it's time to move on.

Just beyond the station platform is an old sign that was aimed at south-bound trains. It simply says, "Stop". Which is what the trains heading into Lambton Colliery had to do after 1988, because another "stop" had hit the line.

There was no longer a manned signal box at Redhead, after the closure of John Darling Colliery further down the line.

The sign is just another artefact of the rail days. No one now is going to follow its order. After all, we're here to move, to slow down perhaps, but to not stop. So I keep going, noting the shift in grade and the quickening of my breath, as I head up the hill.

Without one of Ray's "bank engines" to give me a push, I'm instead motivated by the changing environment, from the wetlands in the low country to the forest creeping in on the slopes.

Yet that is not all that has crept in. A little further up the hill, the landscape looks choked with weeds, including stands of bamboo, as if the environment has gorged on the junk food of our presence. Which, in a way, it has. This area used to be a garbage dump.

But native vegetation reclaims the landscape. Actually, Mother Nature seizes back what is hers, with a gum forest. The undergrowth is made downy by a blanket of ferns, and the atmosphere is softened further by birdsong.

To immerse myself in this environment, I stop for lunch by the track, sitting on one of the benches with frames fashioned from the rail tracks.

Former Lake Macquarie councillor and a prime mover of the Fernleigh Track's development, Laurie Coghlan, told me he wanted to use more rail materials in the benches' construction.

"For the benches themselves, I wanted to use sleepers, but OH and S knocked that on the head, because they were worried about people getting splinters in their bum," he recalled.

I have no splinters in my bum but timber fills my view. While looking at the trees, admiring the calligraphy of nature on their trunks, I dig from my memory shards of poetry, including lines from "The Gum Forest", written by Australia's laureate of rural and bush life, Les Murray.

New trees step out of old: lemon and ochre

splitting out of grey everywhere, in the gum forest.

Little wonder this part of the old line was Ray Cross' favourite section. Rather than just gaze at the trees from the locomotive, Ray loved to look ahead on the descent to Redhead.

"You could see right out across the ocean there," he recalls.

In its new life, as part of the Fernleigh Track, this descent, along with other steep sections, provides a thrill for some cyclists, including those creatures known as MAMILs (middle-aged man in lycra).

The combination of slopes on a popular multi-use path and some cyclists' need for speed has occasionally led to collisions, both physical and ideological, on the Fernleigh Track. Some walkers reckon cyclists should slow down. Some cyclists reckon those on foot should step aside and make way.

Those moments of tension between different users have seemed at odds with one of the goals set out in the 1994 report, The Fernleigh Track. A Living Corridor: "It should accommodate the widest possible range of local users who can amicably co-exist while retaining the tranquility of the natural bushland."

President of Newcastle Cycleways Movement, Sam Reich, acknowledges that in the past there has been some conflict between track users, but it is "very rare these days".

"Over time, the users have learnt to co-exist better," Sam Reich says. "I haven't heard of any serious incidents on the track for a long time."

Pedalling up the hill, speed is not an issue for me.

The track climbs out of the forest and through the cuttings carved and cleaved from the earth by labourers as they created the rail line. I see in the distance, as I approach Whitebridge, a yellow triangle on a post.

In the days of rail, historian Ed Tonks explains, that was an important signal for train crews.

"It's informing the driver that they're coming into a controlled area and there are signals and be prepared to stop," Ed Tonks says.

But with the Fernleigh Track accommodating cyclists and pedestrians, the sign has taken on a different meaning.

That yellow triangle screams, "You're almost there!", for it is perched near the crest of the hill.

This was the highest point along the Belmont Line, at 89.3 metres above sea level. The steam trains that Ray Cross fuelled and guided along this line may have long gone, but by the time I reach the top, I'm doing a reasonable interpretation of one. I'm huffing and puffing.

Tomorrow: From Whitebridge to Glenrock in "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan".

Read more:

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 1 - Pedalling into the area's past and soul

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 2 - From Belmont into the wetlands

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Part 3 - From Jewells to Redhead