For Barry Massarsky, a specialist number cruncher for pop stars and record labels, the financialisation of music has been very good business.

“We are so busy. We are so unbelievably contracted with so many different players . . . new funds are coming in once or twice a week”, Massarsky told the Financial Times in July. “[My business partner] is like: ‘Hold the door shut!’ It’s wild . . . the market is scintillating”.

People who have worked with Massarsky describe him as an eternal optimist — one former client compared him to the mentor in the film Jerry Maguire who says: “I clap my hands every morning and say, ‘This is gonna be a great day!”. But, until recently, the Cornell business school graduate had spent more than a decade toiling in an industry suffering from chronic malaise.

As an economist he calculated the value of music royalties for record labels, publishers and artists. When online piracy disrupted the industry in the 2000s, Massarsky earned his keep by calculating, for example, how much money Bob Dylan stood to lose due to copyright infringement on a website called mp3.com.

But in recent years, music streaming has resuscitated industry revenue, while central banks cut interest rates to historic lows, sending investors searching for new sources of returns. The result: the world’s biggest investors poured billions into what had been a staid sector and music royalty payments were turned into a recognised asset class. Massarsky and his small team became the financial wizards behind billions of dollars in high-profile transactions.

Today, music executives, lawyers and agents say the influx of Wall Street cash is unprecedented. After a string of investments in the sector, Blackstone now earns money every time Justin Timberlake’s “SexyBack” plays in a shopping mall. Apollo gets paid each time Luis Fonsi’s “Despacito” is blasted through a nightclub.

The phenomenon was pioneered by a London-listed investment trust called Hipgnosis, named after an art group that designed album covers for Pink Floyd and others. In 2018 Merck Mercuriadis, a music obsessive who once managed Elton John, created the fund as a vehicle to buy songs, pitching them to institutional investors as a way to make reliable, bond-like returns.

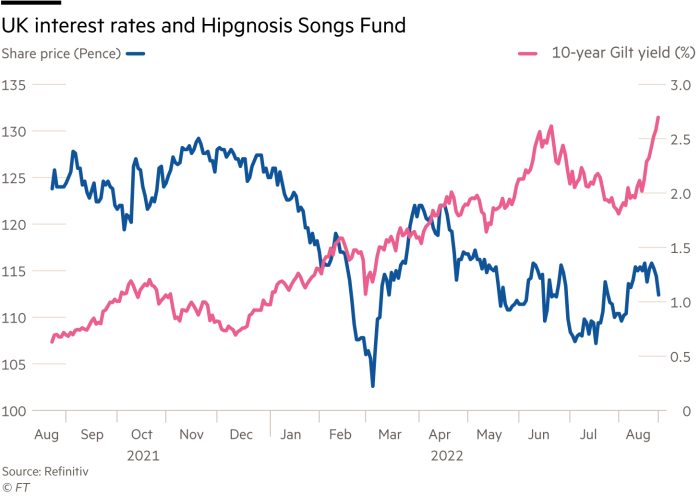

In an era of rising interest rates, the nascent asset class faces its first real test. “What you’re buying is an anticipated future stream of cash flows. If rates go up, you discount those cash flows at those higher levels,” says Dan Ivascyn, Pimco’s chief investment officer. “Music IP [intellectual property], like other private markets, is an area where we haven’t seen the markets fully react to the realities of what we’re seeing in public markets. You’re going to see transaction volumes slow down.”

Under these conditions Massarsky’s role will be crucial. If he were to start using higher interest rates as part of his calculations — reflecting rising real-world rates — the valuation of tens of thousands of songs would fall, potentially wreaking havoc for investors who have used debt towards the purchases. So far he has resisted.

The rich get rich

“Everybody knows the fight was fixed. The poor stay poor, the rich get rich,” Leonard Cohen sang in his 1988 hit “Everybody Knows”.

Blackstone — the private equity titan whose chief executive, Stephen Schwarzman, made more than a billion dollars last year — not only owns rights to that song, but has packaged it up with a host of others and securitised it as collateral against hundreds of millions of dollars of debt.

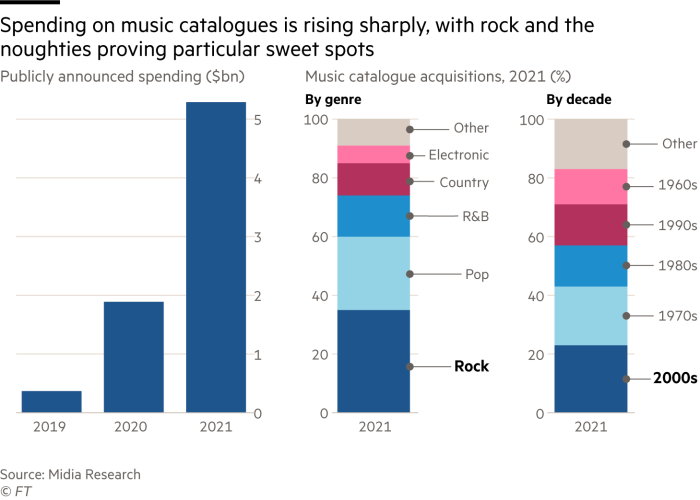

The tale of how that happened traces the story of post-financial crisis capitalism. When Mercuriadis founded Hipgnosis in 2018, interest rates were low and the stock market was in its ninth year of a historic rally. As recently as 2019, only $368mn worth of music catalogue deals were announced publicly, according to Midia Research. But as investors made creative attempts to generate higher returns than the measly sums on offer from government bonds, an investment case for songs was developed. Music catalogue dealmaking ballooned to $1.9bn in 2020, then to $5.3bn in 2021, says Midia.

The rationale went like this: by collecting a wide range of songs together in one fund, their royalties — paid to copyright owners when a song is played — could be aggregated into a steady stream of cash flows from which to pay dividends. Big investors such as Pimco and Apollo were lured into music royalties for the first time.

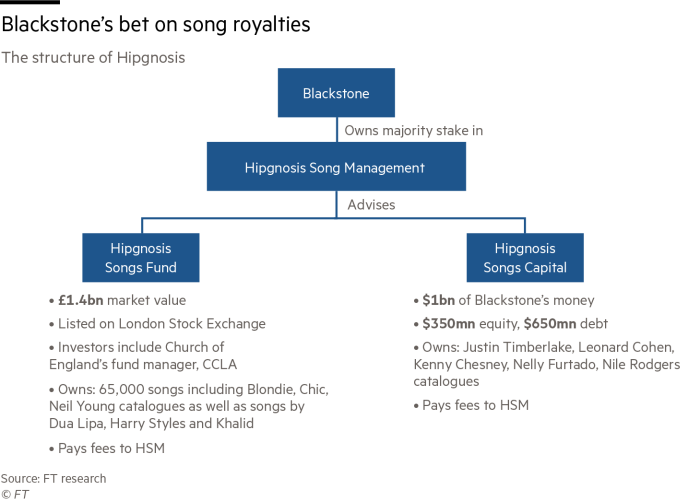

Amid the rush, groups including Investec Wealth & Investment, Aviva Investors and the Church of England’s fund manager, CCLA, gave their money to Mercuriadis’s London-listed investment trust Hipgnosis Songs Fund, which has spent it buying copyrights to more than 65,000 songs.

“We think this investment will generate supernormal returns . . . it’s less well known [than other asset classes] and we think we’re early to this,” says Paul Flood, a portfolio manager at Newton Investment Management, which as of HSF’s latest annual report was its largest shareholder with a 10 per cent stake.

Mercuriadis hired Massarsky as a third-party agent to calculate the song portfolio’s “net asset value” to present to his shareholders. By Massarsky’s calculations, Hipgnosis seemed to be making prophetically successful bets. Every six months, Massarsky calculated that the portfolio, to which songs were constantly being added, was worth more and more: from £128mn in March 2019 to $2.7bn at the end of March. (Hipgnosis’s reporting currency changed from sterling to dollar).

Meanwhile Mercuriadis sealed his reputation as a friend to the stars, positioning himself as a bridge between stuffy investors and erratic musicians. He waxed lyrical in interviews about how songs were “better than gold or oil” as an investment. As his fund bought more songs it reported ever-rising revenues — from £7.2mn in 2019 to $168.3mn by March this year — and financiers rallied behind it. Four of the six banks that cover the stock — JPMorgan, the Royal Bank of Canada, Investec and Liberum — have a buy rating.

But the pace of acquisitions masked the underlying performance of the catalogues. The pro forma royalty revenue these songs generate — a measure that strips out the boost from new purchases — has been falling for at least the past two years, ever since it was first disclosed.

As of the end of August last year, Mercuriadis’ London-listed fund had invested all the money it raised for song catalogues. It can no longer raise more without diluting shareholders — the share price is trading too far below the valuation that Hipgnosis Songs Fund derives from Massarsky’s numbers. With that public fund effectively frozen, Mercuriadis now relies on Blackstone for funding.

Last year Blackstone bought Hipgnosis Song Management, Mercuriadis’s management company, which advises the listed fund. Blackstone also set up a separate $1bn fund, Hipgnosis Songs Capital, from which to do more song deals, which HSM also advises. Mercuriadis used some of this cash to buy the catalogues of Cohen, Timberlake and others for the Blackstone fund.

In August Hipgnosis Songs Capital issued $222mn of asset-backed securities, or bonds that use song copyrights as collateral, to help finance its acquisitions. Chord Music Partners, backed by Blackstone’s rival private equity group KKR, had arranged a similar securitisation in January, tied to about 62,000 songs. But HSC will have to pay more than 6 per cent a year for its debt, compared to just under 4 per cent paid by Chord, in a sign of how rising rates are already eating away at potential returns.

Blackstone is now imposing greater financial discipline, using data analytics and spreadsheets to assess potential returns, say two people with knowledge of the matter.

“A lot of deals that were totally irrationally priced 12 months ago, the irrational behaviour . . . is out of the market,” says Hartwig Masuch, chief executive of music company BMG, which has partnered with KKR to buy $1bn of music rights. “There’s been a little acknowledgment with some of the backers of financial vehicles, that it’s not enough that you’re able to spend money. You have to make sense of what you buy.”

A basket of good

Even as economic conditions sour, Wall Street giants are still competing for hit songs against traditional buyers — the major record labels — as well as smaller specialist funds. Blackstone has doubled down on its Hipgnosis investments. KKR re-entered the music business after a decade away, with a new billion-dollar fund. Carlyle, after helping finance a $300mn acquisition of Taylor Swift’s former record label in 2019, has committed $500mn to buying songs — even after being dragged into a bitter feud that led Swift to re-record her catalogue.

“If you think about investing in a lot of other asset classes right now, it’s pretty treacherous. There’s inflation, there’s supply chain risk, there’s geopolitical risk,” says a senior executive at a major private equity group. “Music is relatively immune to those things”.

Massarsky’s consulting practice, which was sold a to larger accounting group Citrin Cooperman in January, with a team of five, is involved in about three-quarters of all deals in the market.

Hipgnosis’s listed vehicle uses Massarsky’s asset value calculation as a measure of success and also a determinant of its borrowing: the fund is allowed to borrow 30 per cent of the equity value derived from Massarsky’s figures. Mark Mulligan, a music analyst for Midia, says this structure can create a “virtuous cycle” as Hipgnosis’ catalogue is revalued by Massarsky every six months.

“Hipgnosis goes to the market and says: this is how much our asset has increased in value,” says Mulligan. “Not how much income has increased, but how much the valuation . . . has increased. So much of what drives the value is simply: how much are people willing to pay? How much they are willing to pay is shaped by the valuations . . . It’s this echo chamber.”

The head of one major music buyer says Massarsky “validates a lot of valuations that we would not accept as a price”. “Remember that problem of the rating agencies in 2007?” says Michael Sukin, a music lawyer who hired Massarsky as an economist for American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers in the 1980s, referring to the subprime mortgage crisis.

The Massarsky Group says its work is “strictly independent” and that the firm is “compensated solely for our expertise . . . We do not validate valuations, that is simply not part of what we do. We conduct independent valuations that reflect, to the best of our ability, what the market would bear.”

The investment trust model, which benefited Hipgnosis in previous years, has become a problem for the company in recent months. Increasingly its public stock is trading out of line with what Massarsky’s estimates say the portfolio is worth — a gap of about 30 per cent. Massarsky Group’s calculation of the net asset value of a song catalogue is determined using a discount rate — an interest rate to help calculate the current value of future cash flows. The higher the discount rate, the lower the current value, and vice versa. Even as the Fed has aggressively raised interest rates this year, the group insists it does not need to increase its discount rate.

Nari Matsuura, a partner at Citrin Cooperman and member of Massarsky’s team, says: “We can’t change our discount rate week to week, it would be irresponsible. A proper discount rate takes both the present and future into account and our current discount rate accommodates for that, which is why we think it’s appropriate for the time being”.

If the group did mark down valuations, Hipgnosis Songs Fund would be prevented from borrowing much, or any, more. It has already borrowed $600mn, about 27 per cent of its $2.2bn operational equity value, close to its upper limit of 30 per cent. A major markdown, from $2.2bn to $1.5bn, would risk putting the fund in breach of the terms of its loans from JPMorgan and forcing it to repay some debt.

Hipgnosis executives privately tout Blackstone’s involvement as a reassuring factor for shareholders in the original, listed fund, saying that if the share price falls the Wall Street private equity group could step in and buy its catalogue, putting a floor, of sorts, on its value. But Flood, from Newton, is wary of giving Blackstone too easy a path to snap up the catalogues cheaply.

“If Blackstone made a cheeky bid, we would tell the board to see every record label on the planet and every other private equity firm” to get the highest possible price for the songs, he says.

When the music stops

A broader culture clash is being felt in the music industry as Wall Street enters a sector that had been used to operating more informally, with deals subject to the whims of big personalities and personal relationships.

Securitising songs has led to some unusual forms of financial analysis, such as a Kroll report that last month told bond investors a cover of Cohen’s “Hallelujah” by Pentatonix, a US a-cappella group, accounts for more than three times as many Spotify streams as the original. It also beats Jeff Buckley’s cover. When 10 different versions of the song “Hallelujah” are added together they account for almost 13 per cent of the Blackstone catalogue’s royalties.

Retrieving royalty payments — the lifeblood of these deals — can be a cumbersome process. One music company chief executive says that often, one of the most difficult obstacles to buying an artist’s catalogue is that the musician cannot find their physical master copy.

Blackstone executives believe they can extract more money from music through more sophisticated management, say people familiar with the matter. The rationale is that songs can be managed in a similar way to other assets: returns can be boosted by, say, persuading filmmakers to use songs from your catalogue, or bringing in royalty payments more quickly and efficiently.

The question now is whether financiers can find a way to profit despite soaring inflation and higher interest rates — and what will happen to investors’ cash if they find they cannot.

Private equity executives often cite Goldman Sachs in validating their music investments, calling the bank’s annual music report the “bible” of the market. Goldman predicts music revenue will nearly double to $153bn by 2030, as streaming revenue rises 12 per cent per year on average.

But recent numbers tell a different story. Warner Music reported that second-quarter streaming revenue grew less than 3 per cent from a year ago, while market leader Universal said subscription streaming sales rose only 7 per cent after years of double-digit growth.

Yet through it all, Massarsky is bullish. He cites new ways of making money from songs, such as payments when they are played on Peloton bikes or TikTok. “We are absolutely amazed at the growth,” he said in July, as stock markets lurched. “It is a basket of good.”

Additional reporting by Brooke Masters and Harriet Agnew

Photographs: Dreamstime/Getty Images/Reuters/Paul Bergen/Redferns