While generative AI can produce images with superficial visual appeal, especially to those who haven’t seen much AI art, they tend to fall apart under closer inspection. Elements are assembled almost randomly, and the overall image lacks the meaning, coherence and intention that can only come from a human artist.

A way artists can fight back against generative AI is to lean into the things that only a human can do, for example using narrative to capture emotion, and convey something personal about themselves in their work. (Check out our collection of the best digital art software and drawing tablets to optimise your art journey).

Paint with words

Some narratives will work better than others in paintings. Consider situations that feature opposing forces or some form of tension. Senior concept artist Titus Lunter says: “Interesting stories are inherently about conflict.”

Once you’ve found your conflict, you need to define it in words. Your choice of words is important, because these will be the keywords that you use to build your image. Titus explains keywords “are broadly understood by most people, but mean very different and personal things to everyone”. For example: “While cosy might be under blankets, it also might be by a fire, or on a patio with a nice drink.” These are all literal scenarios that you could paint to evoke a feeling of cosiness. “Understanding that these words mean different things to different people will help you understand your own voice,” Titus adds.

Your unique voice and perspective is what makes your work different to everyone else’s. He says: “In a way, you and your painting are having a dialogue on how to best capture what you want to say and what that means.” This happens in two ways: your choice of what to paint, and how you use elements such as the composition, colour and texture used to paint it.

“One of the things that gets easily forgotten nowadays is that painting, and thus storytelling, is a deeply personal journey, which comes to be thanks to introspection, exploration, and creating a bunch of terrible paintings,” Titus explains. “The end result is a reflection of the journey you’ve gone on to try and define these keywords in a way that fits you best as a painter.”

Some of the best stories you can work with are those that are familiar to people, such as folklore and ancient mythology, because a fresh take on something people think they already know about is usually compelling. These types of stories are often told through the language of symbolism.

Similar to Titus’s use of keywords, he adds that “symbolism walks a tightrope between being deeply personal and universally understood. The biggest mistake people make is to be too literal and put all their eggs into one basket by trying to tell the entire story through just one of the fundamentals, like the drawing, or the colour, and so on. But the trick with using symbolism is to pick which part of the story you want to lay on thick, and which you simply allow the viewer to arrive at themselves.”

Use your experiences

An artist whose narrative-heavy body of work is largely based around creating retellings of traditional stories is Amanda “A.J.” Ramsey. Her way of going on the journey that Titus describes is to first lay out the scene that will convey the familiar story to an audience, and then “think about my own personal experiences, and how they relate to the story I want to tell”.

In one of her paintings, which is based on the Ancient Greek Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Amanda added roses and twisting tree branches to the background. She explains: “They give me a feeling of youthfulness, nostalgia, and a sense of mystery that’s entirely personal to me.”

She also added blackberry bushes because they are something from her life, and because they have symbolic meanings relevant to the story. This is a key technique for Amanda; to use elements that are deeply personal to her but also have universal meanings for others to perceive.

She offers a word of warning for those who put a lot of themselves into their art: “Be prepared for nobody to understand your artwork,” she says. “Don’t be upset; they’re just reflecting their own experience and knowledge of the story you’re trying to tell.”

Folklore and traditional stories are often culturally significant and held up as almost sacred by some. Amanda is sensitive to this. “I try so hard to do it justice,” she says. “I research a lot before committing to a piece. I’ve denied creating paintings because I didn’t know enough and was worried I would disrespect it.”

Show your respect

Another artist who draws inspiration from mythology and folklore, Kim Myatt agrees that sometimes there is a responsibility for artists to be respectful towards the original work.

“On the one hand I believe all artists should be free to represent whatever inspires them in whatever way they want. But on the other hand, if it’s released on the internet especially, people will take the artist’s rendition as gospel and consider it ‘canon’. This can be bad when folklore taken from a specific culture is attached.”

Kim has first-hand experience, having seen this happen to elements from her own culture. She reflects: “Although it’s nice to have something recognised, it’s annoying to see things added that weren’t there originally, especially when the original folklore it’s drawing from has been crushed by colonialism and needs preservation.”

Kim’s images tell deeply personal stories about her own life, and she uses her art as a source of comfort. One of her paintings depicts a woman laying beneath her duvet, mingled with autumn leaves. It’s about going through a difficult time, “wanting to escape into a dream and wake up when the stress is over,” she says.

In another, we see a boy being manipulated by disembodied hands that represent the influence of other people’s opinions. Of the piece, she explains: “I wanted to express the idea of how words from your past can push and pull you in directions you might not want to go.”

Kim points out that your use of symbology is going to land differently with every viewer. “Something that makes me cringe might be cool to someone else,” she says, before also explaining that she thinks similarly to Amanda. “I find it helpful to develop your own understanding of motifs and symbols – what do these things mean for you – and mix that into the use of more universal symbolism.”

Use simple symbolism

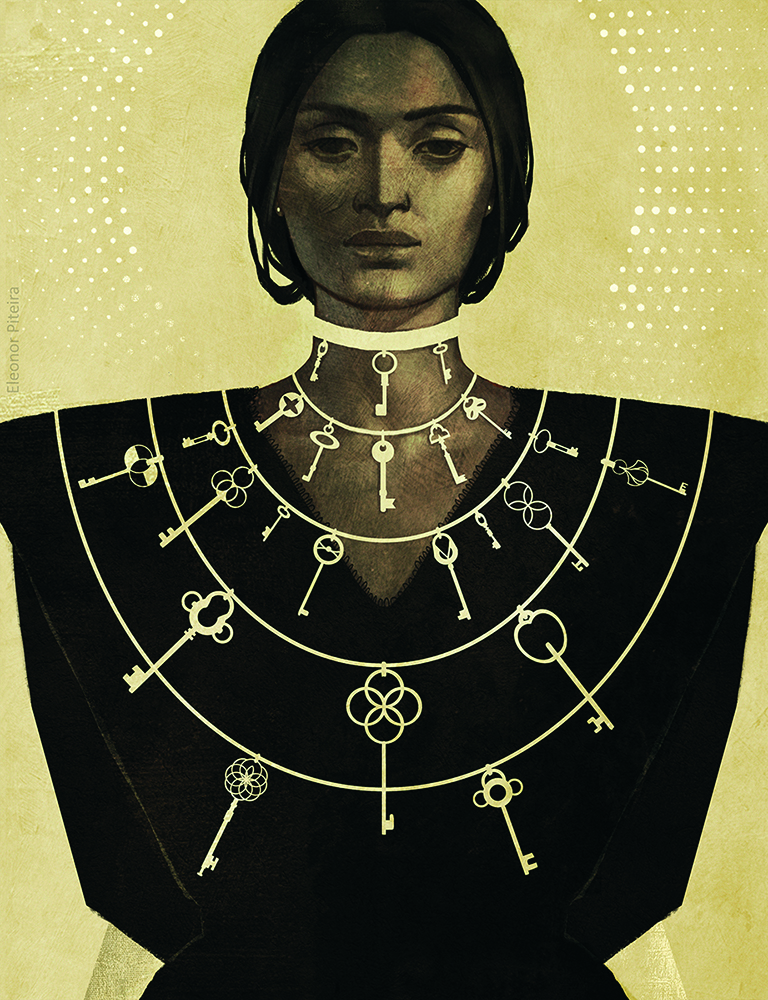

In her work as a freelance illustrator, Eleonor Piteira creates images for book covers and trading card games that convey a specific narrative. Her advice is to simplify your idea, as it’s easy for your point to get lost if you use too many symbolic elements. “Choose just one element for the focal point, and build your illustration to serve the purpose of bringing attention to that,” she says.

“You’ll want to make sure the most important elements in the illustration are readable. You want people to look at your illustration and understand what they’re seeing, so you can hook them into looking at your work with more attention.”

If there are secondary elements that are key to your story, you can draw

up a hierarchical list and give them an appropriate level of prominence within your image. “It’s all about being intentional with your choices,” she says. “But not everything needs to have a reason to be there, sometimes it might just be because you like it. The cool factor should not be ignored, so have fun with the process!”

This content originally appeared in ImagineFX magazine, the world's leading digital art and fantasy art magazine. ImagineFX is on sale in the UK, Europe, United States, Canada, Australia and more. Limited numbers of ImagineFX print editions are available for delivery from our online store (the shipping costs are included in all prices).