Along with revealing the oldest galaxies in the universe and shedding light on the birth of stars, the James Webb Space Telescope will help us seek out life on other worlds — if it exists. We talked to the experts about how the telescope will aid the search for habitable planets and whether it could spot something like a Dyson sphere, and where we should look.

How will the Webb Space Telescope look for aliens?

If aliens exist, they need a place to live, so astronomers’ first goal with Webb will be to find exoplanets that are located in Earth-like temperatures where liquid water is likely to be stable.

But an address in the habitable zone doesn’t guarantee a livable planet — for instance, Venus, Earth, and Mars are all in the Sun’s habitable zone.

“Every rocky body in our own Solar System seems to have a different atmospheric composition,” Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory astronomer Kevin Stevenson, whose team will use Webb to study nine exoplanets starting in July 2023, tells Inverse. "When you look at the four rocky planets in our own solar system, Venus has a very thick carbon dioxide atmosphere, Earth has a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere with oxygen, Mercury has a very thin nitrogen atmosphere, and then Mars has a thin carbon dioxide atmosphere.”

Some habitable zone planets in other planetary systems could be worse off and not have atmospheres at all, which would eliminate a protective barrier from its star.

The next question, of course, will be what alien atmospheres are made of. And the possibilities are endless — so much so that one of the first goals for researchers will be just trying to understand them.

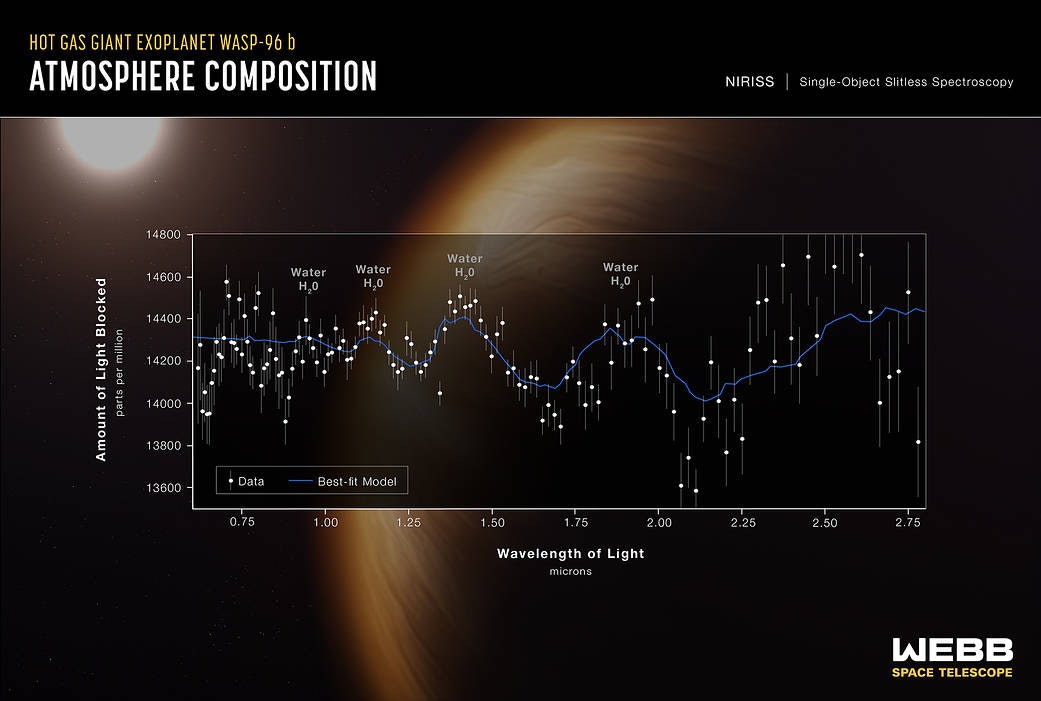

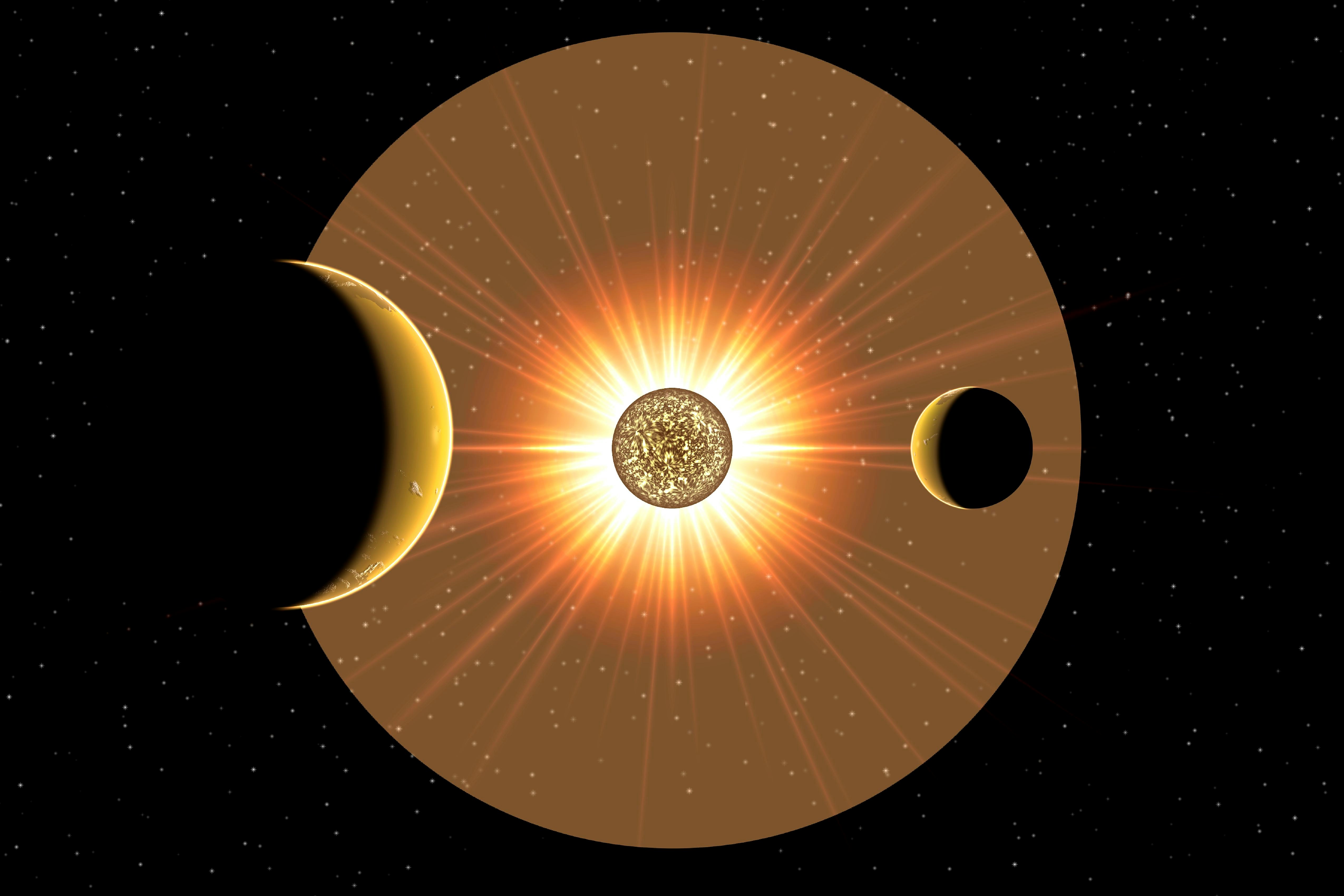

To figure out which planets have the right stuff for life, Webb will help astronomers “see” how thick exoplanet atmospheres are and what they’re made of. As an exoplanet passes in front of its star, the starlight gets filtered through the exoplanet's atmosphere, where certain molecules absorb particular wavelengths of light. Webb’s Near Infrared Spectrometer, or NIRSpec, can spot evidence of specific chemicals, such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor in the atmospheres of distant planets.

“What we hope to see is signatures of carbon dioxide, which should have a really looming feature in this wavelength range. But it could also be that we see signatures of things like water,” Nikole Lewis, a Cornell University astronomer, tells Inverse. “Once we know how much carbon dioxide there is in the atmosphere, or how much water there is the atmosphere, what we can start to do is run scenarios for its climate.”

Lewis and her team will start observing exoplanet TRAPPIST-1e in June 2023. The TRAPPIST-1 system has seven Earth-sized worlds, and TRAPPIST-1e is one of three that could be habitable under the right conditions. The team’s first set of observations will focus on looking for carbon dioxide and figuring out if the planet has a thick, thin, or non-existent atmosphere. If carbon dioxide is found, subsequent observations will look for water and methane.

Is anyone home? — If a world has the right conditions for life, astronomers next want to look for biosignatures — chemicals potentially produced by living things — in alien atmospheres. Biosignatures could include things like oxygen and methane, along with more obscure compounds like phosphine. But many of these chemicals can be produced by other means, including volcanoes.

Several rovers and landers have sniffed out methane (best known here on Earth for its starring role in cow flatulence) on Mars. But so far, planetary scientists are still debating whether methane on Mars came from trapped gasses from ancient volcanoes, or massive alien farts. Detection of phosphine in Venus’ atmosphere based on archival data announced in 2020 sparked heated debate on a few fronts: if phosphine is definitely tied to life, and if the phosphine was actually detected at all.

The debate on both Venus and Mars is still raging, and you can safely expect the first suggestion of biosignatures on an alien world to kickstart an even fiercer one.

Spotting aliens via pollution — SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) researchers like Pennsylvania State University astronomer Jason Wright say data from Webb may make it possible to take the search for aliens a step further: looking for evidence of advanced civilizations with the technology to change their worlds.

“Sort of a newish thread in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence is seeing what atmospheric pollutants we might be able to detect,” Wright tells Inverse.

Here on Earth, the most prolific pollutant in our atmosphere is carbon dioxide, but from a cosmic distance, it wouldn’t be obvious that a supposedly-intelligent species put it there. After all, Venus’ atmosphere is full of carbon dioxide that occurred naturally.

Instead, Wright suggests looking for pollution that’s harder to pin on natural causes, like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), widely used as coolants, propellants, or solvents from the 1920s to the late 1980s. CFCs aren’t produced by natural processes and were largely responsible for the hole in the ozone layer. CFCs could be a sign of an alien civilization advanced enough to create artificial chemicals and pollute their atmosphere.

“They're a very small component of the atmosphere, but they're actually quite detectable,” says Wright, who along with his colleagues recently ran some computer simulations to find out whether Webb’s instruments might be able to spot CFCs in the atmosphere of an exoplanet.

It turned out that although CFCs and nitrogen compounds produced by fertilizers would be difficult for Webb to pick out in an exoplanet’s atmosphere, it’s technically possible. (The study used TRAPPIST-1e as an example.) Wright describes it as “borderline,” and says he’s encouraged by the result.

“Just the fact that the first [chemical] we checked, there's a planet where it's borderline possible, really shows that we're right at the cusp of being able to detect these kinds of atmospheric technosignatures,” he says.

What about Dyson spheres and alien megastructures? — Webb, of course, can’t help us look for alien radio signals, because it’s an infrared telescope, not a radio telescope. But it may be an excellent tool for finding really dramatic technosignatures, like Dyson spheres, planet-sized ways to capture a star’s energy.

“JWST should actually be quite good for things with Dyson spheres, because it's in the infrared, and it goes out long enough in the infrared that something like a Dyson sphere should be emitting in a way that it can detect,” Wright says.

But the Space Telescope Science Institute, the organization that manages Webb as well as the Hubble Space Telescope, is vanishingly unlikely to grant observation time to a search for Dyson spheres. Instead, Wright suggests that it could be used to get a closer look at star systems where something unusual — and possibly megastructure-like seems to be happening.

Wright was involved with a team that looked at an oddly dimming star called KIC 8462852 or Boyajian’s Star. Among many speculations for why it kept blotting out was the possibility of a Dyson sphere. Astronomers taking a closer look at the system found that an unusually large amount of dust was the culprit, but Wright points out that even if Webb doesn’t find aliens at the next version of Boyajian’s Star, “That will be sufficiently interesting in its own right, even aside from technosignatures.”

Where will the Webb Space Telescope look for aliens?

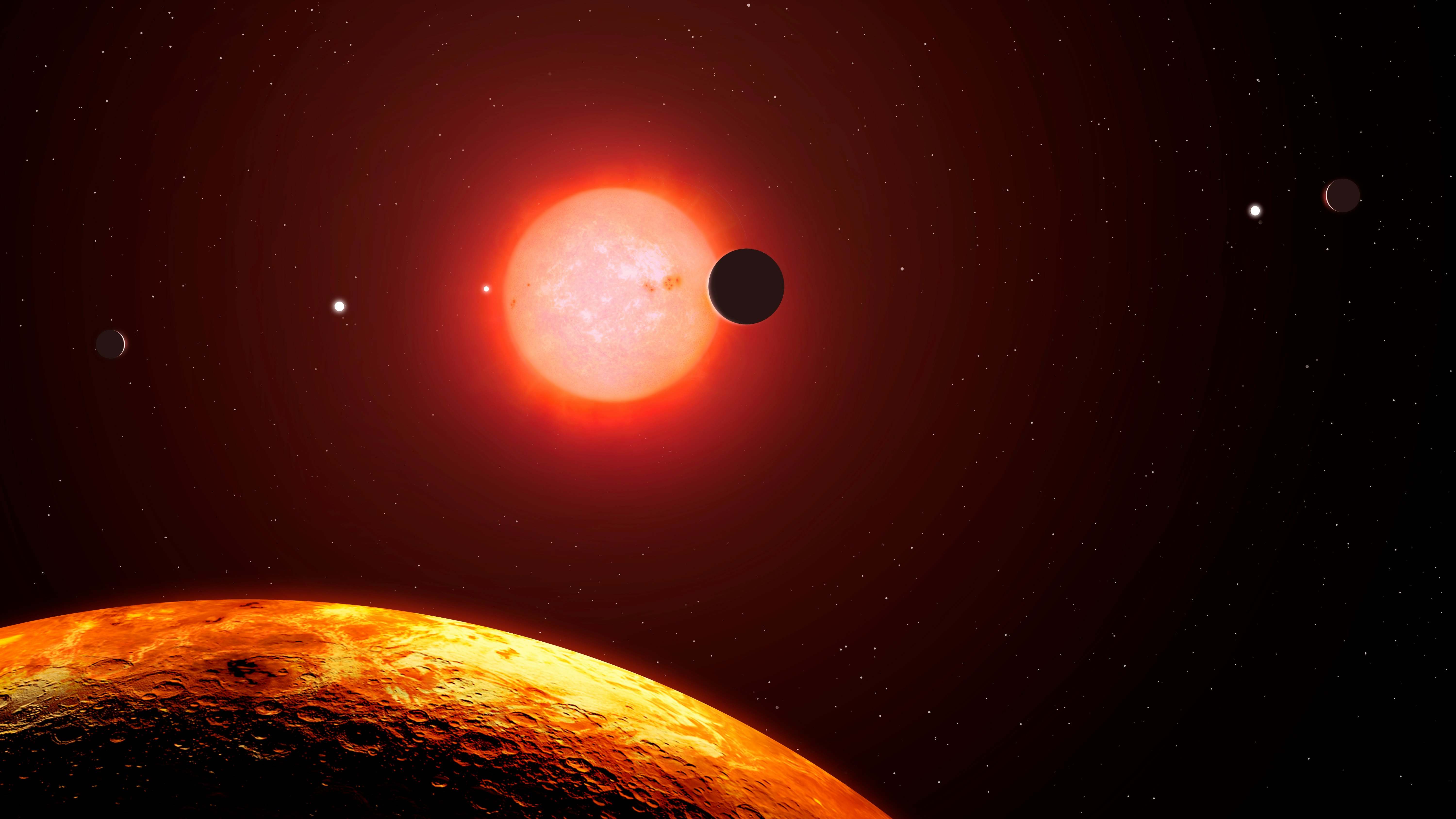

One thing Lewis’s and Stevenson’s research has in common is that both focus on rocky planets, like our Earth, orbiting small, relatively cool stars called red dwarfs, not at all like our Sun. TRAPPIST-1 is a red dwarf, as is Proxima Centauri and the recently-discovered SPECULOOS-2, both of which have habitable zone planets. Of the 21 known habitable zone planets likeliest to have the right temperature for life, 19 orbit red dwarfs, according to the Planetary Habitability Laboratory.

Because they’re small, cool, and slow-burning, they form more often and live longer than brighter, more massive stars. In addition to their sheer numbers, a habitable zone planet orbits in a shorter amount of time around a much dimmer star than the Sun, allowing astronomers to take several glimpses of a planet as it passes in front of its star and coax out more details — whether for atmospheres or for CFC-like technosignatures.

“Having small stars really helps us in terms of measuring that signal,” says Stevenson. All nine of the planets in his team’s observations orbit red dwarfs, and he’s a member of the Consortium for Habitability and Atmospheres of M-dwarf Planets, or CHAMPs.

Will the Webb Space Telescope find aliens?

Nobody knows when or if Webb — or any other telescope or SETI project—– will find evidence of life on another world. But the odds of finding a habitable world, or even potential biosignatures are high enough that several teams of astronomers and astrobiologists have been granted valuable time on the telescope to look for them.

At this point, a better question might be “How will we know if Webb has found aliens?” And that’s an even tougher question to answer.

“Even when we start to get some sense that [a planet] is habitable, it has an atmosphere, and maybe the surface isn't a hellscape, it's gonna take time and a lot of discussion among the community to say that this combination of molecules in the atmosphere is indicative of life,” says Lewis.

The best ammunition in that kind of scientific debate is more data. For instance, to figure out what’s actually happening on a distant world, astronomers will probably have to look for certain combinations of chemicals — ozone and water vapor, for instance — instead of just a single biomarker.

Webb might also help scientists measure how much of a particular chemical is present in the planet’s atmosphere. If, for instance, there’s a very tiny amount of methane, researchers can compare that information to models of how the planet’s geology and atmosphere might work, which could shed some light on whether microbes, alien cows, or volcanic vents are more likely to produce exactly that amount of methane. But it’s still going to be an extremely tough question to answer with any certainty.

And just like biosignatures, finding one potential pollutant, like CFCs, in a planet’s atmosphere isn’t the same thing as finding proof of alien life. It’s more of a strong hint.

“It's not quite the smoking gun that finding radio waves would be. If we found narrowband radio signals coming from space, that can only technological,” says Wright. “It's not 100 percent until you find some other signal that is 100 percent or lots of different [chemicals], all of which are probably technological.”