It’s a sunny, spring Saturday morning in early 2019 and I’m having coffee at the local Costa in Brentwood, an Essex town where I’ve never been before. There are plenty of people out and about and smiling. I have a couple of hours to spare so I’m planning to wander around and have a look in the shops. Then my phone pings: “Surprise!” It’s a promotion from M&S. “Here’s 20% off when you shop online”.

The Brentwood branch of M&S is just a couple of doors down from where I am – I just passed it. But the notification isn’t suggesting I go there. On the contrary, this special offer will deter me from shopping in an actual shop, on an actual high street, where I know I’d now be paying 25% more (if you start from the lower price) than I would if I bought online. It is, in effect, a counter-advertisement – taking me away from the shops and towards a virtual, online-only future.

Around this time, M&S had been closing stores in numerous locations. Many of these shops had been there for as long as people could remember, and were part of the towns’ identity. Like “our” NHS, and unlike most other commercial brands, M&S evokes a feeling of belonging to a shared history.

Looking back, my little counter-epiphany now seems to encapsulate something of the fraught shopping mood of three years ago. The incident felt like a painful sign of the contradictory state of British retail – and especially that part of it that is commonly known as the high street.

The choice on offer was absurd for both the customers (only one rational way to go), and the company (why push customers away from the stores that are still in use?). But it was somehow feasible then, in those innocent pre-pandemic times, to take for granted the inevitable triumph of online retail, even if it brought with it the destruction of most other modes of buying and selling.

From pedlars to supermarkets

Online shopping seemed in those days to be the next and natural step along the path that began with the introduction of self-service. I started charting these developments more than 20 years ago when I wrote Carried Away: The Invention of Modern Shopping. And a year after the sad Brentwood episode, at the start of 2020, I was coming to the end of writing my new book Back to the Shops: The High Street in History and the Future. This investigates the different stages of shopping, from its early beginnings to the present.

This history stretches back to pedlars and weekly markets and runs through small fixed shops in towns and villages to the grand “destination” city department stores of the last part of the 19th century. Then, in the later 20th century, came self-service, to be followed in recent years by the move online.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

But shopping history never moves in one single direction or all at once. There have always been regional and chronological divergences from mainstream developments. There are also retailing modes that fall by the wayside and then return at a later date in new guises or with new names. They often have every appearance of being newly invented.

Take fast fashion, for instance. We think of fast fashion as inseparable from a contemporary culture of rapid turnover. But a version of it can be found as far back as the 18th century, well before garments were mass-produced in factories. Clothes at this time were all sewn by hand.

In late 18th century London, a new type of shop appeared where, for a price, a lady or gentleman could commission a customised outfit that would be made up for them overnight. It offered an instant transformation into the style and class of the best social circles. But unlike modern fast fashion, it wasn’t cheap and the clothes weren’t flimsy or soon discarded.

The same period also saw the arrival of short-term shops not unlike those that we now call pop-ups. They might appear in any village, when an itinerant salesman rented a room in the local pub as a temporary location for what he’d present as a flash sale: “now or never”. In the 1760s, for example, Thomas Turner, who kept the main shop in the small Sussex village of East Hoathly, complained in his diary about just such a character zooming into the area – and taking away attention, and trade, from his own steady service.

Today, pop-ups move into empty shop units on a short-term basis and at a lower-cost rental. It is a useful arrangement for both the owner of the premises and the shopkeeper. The landlord gets some (if not all) of their usual income for a space that would otherwise be yielding no income, while the tenant, with no long-term commitment, takes no great risk. The business itself – often selling time-limited, seasonal stock – is here today and gone soon after.

Mail order shopping also has a rich history that seems to anticipate later developments, too. Catalogue companies, like Freeman’s or Kay’s, were massively popular in the middle decades of the 20th century. But despite its popularity, “the book” (the affectionate name for the big, “full colour” catalogue) never posed a threat to the shops. Nevertheless, mail order was a form of virtual shopping at a distance, and now looks like a striking precursor to online shopping.

Perhaps the most surprising example of an early retail development whose beginnings have now disappeared from view, is the chain store. We tend to think of chain stores as having pushed independent shops out of the way in the late 20th century, with the result that every shopping mall and every high street (if it survives at all) looks like all the rest. But, in fact, chain stores were everywhere a century earlier, including some of the names that are still well known today.

Chains took off in the second half of the 19th century. Nationwide grocery companies like Lipton’s or Home & Colonial had thousands – yes, thousands – of branches by 1900. Of these early chains (or “multiples” as they were then called) only the Co-op remains. The Co-op no longer maintains the cultural and trading pre-eminence it had from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. But unlike the other dominant chains of that era, it has endured. It even pioneered the move to self-service in the middle of the 20th century and it remains a significant player among the biggest supermarket chains of today.

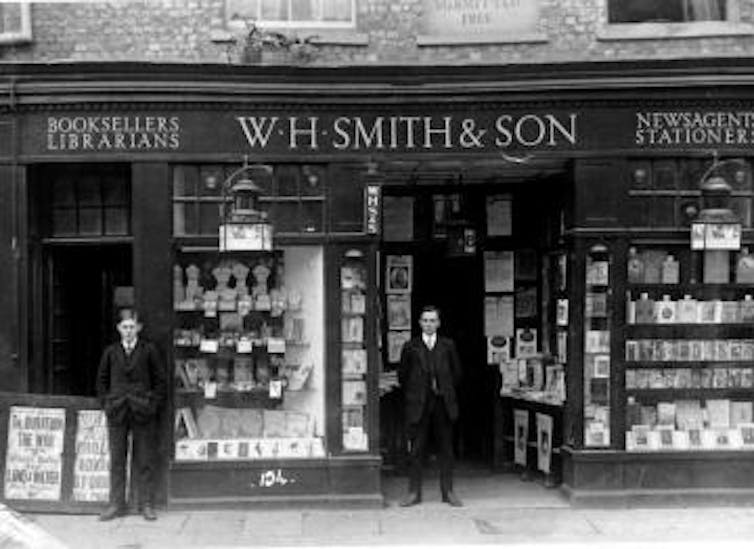

WHSmith, the newsagent and bookseller, developed from the late 1840s alongside the growing railway network. There was soon a stall to be seen inside every station of any size, providing the passenger with novels or newspapers for their journey. In 1900, there were no fewer than 800 branches nationwide. From the beginning of the 20th century, Smith’s also had outlets on town shopping streets.

Boots the chemist was another 19th-century chain that is still a standard high street presence. The first Boots shop was opened in Nottingham in 1849. By the turn of the century, there were around 250 branches – and 1,000 by the early 1930s.

Numerous small and large chains, selling many types of commodity, faded away, died their deaths, or were taken over. But the striking point is that chain store Britain is nothing new. It dates back well over a century.

The self-service revolution

If online retail was the new feature of early 21st century shopping, self-service was the shopping revolution of the 20th century.

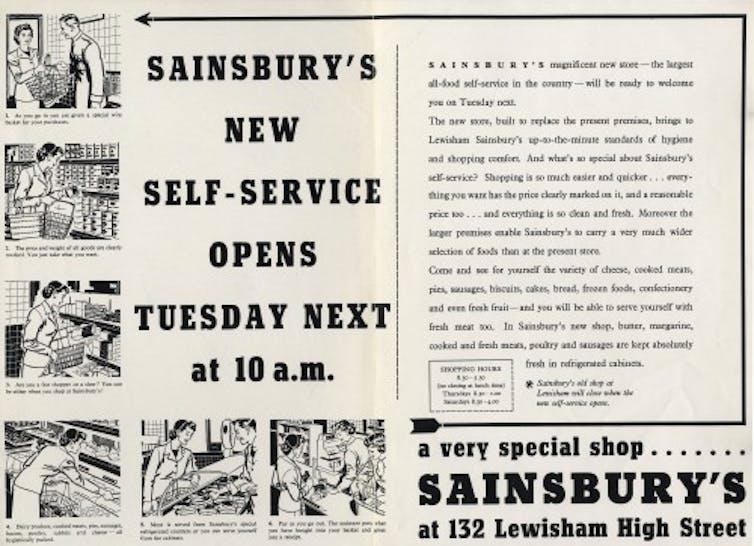

Self-service reached Europe after the Second World war. In the US, it had been an accidental invention of the Great Depression, when abandoned factories and warehouses were turned into makeshift, cut-price outlets. Customers picked out goods as they walked around and paid for everything at the end. By the 1940s, this new type of store was well established, often in regional chains, as the “super market”. Postwar, this new American mode of retail operation was exported to the rest of the world.

Promoted as a modern, efficient way to shop, self-service entailed both a different type of store layout and new norms of customer and shopworker behaviour. Before this, every purchase made was asked for over the counter, item by item, and the assistant “served” the customer personally. Few goods were packaged, so every order was literally customised: measured or weighed and then wrapped.

But self-service did away with all this. There was no need for counter service if customers were making their own selections. All available goods were put out on display, within reach. No need to ask someone to fetch them. And there was no one else waiting behind you for their turn to be served. You could take your time, look around – or get it done at speed. It was your choice.

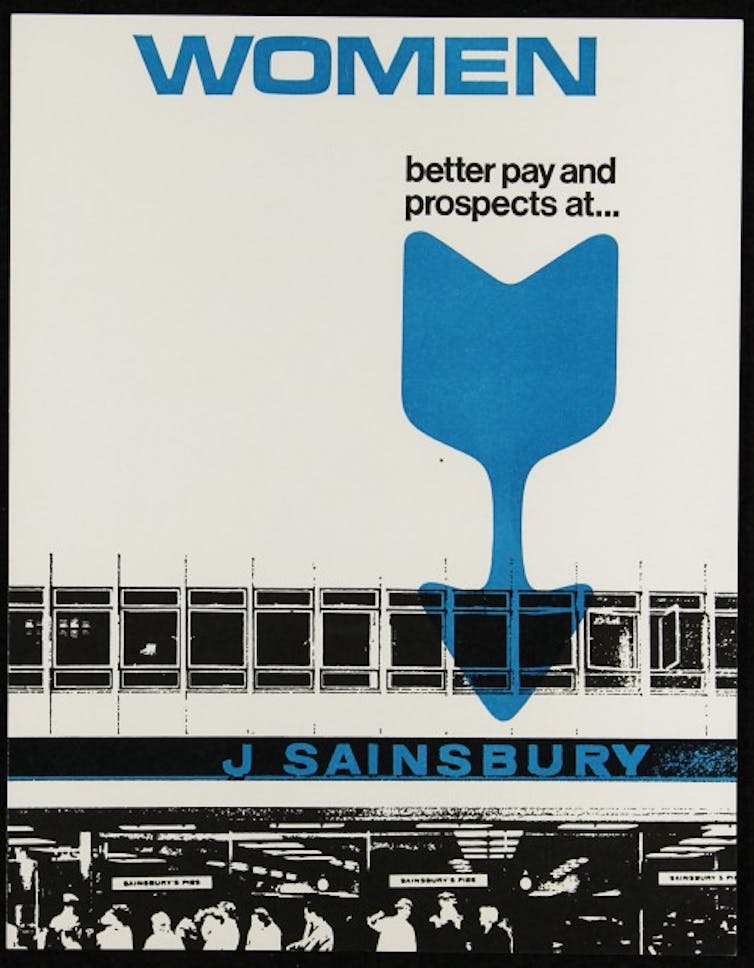

This was a newly impersonal shopping environment. The customer was in control of the pace and the selection, but they were on their own and there was no longer someone standing there to serve them. For shop workers, meanwhile, the abolition of counter service meant that their various skills, including their people skills, were made redundant. So too was their often detailed knowledge of the products they sold.

When the customer did encounter a person across a counter, it was not to ask for advice about what to buy; it was simply to pay and get out. Now they just handed over a basket of goods already picked out; the assistant was not involved in the choosing. Nor was the checkout for chatting. Like factory workers, cashiers had to keep up to speed.

The whole process was meant to be more efficient, a saving of time and money for the benefit of business and customers alike. The customer, notably, was seen now as someone for whom time was a finite and valuable resource. In this way the shift to self-service was perfectly matched with some large social changes of the postwar decades.

As late as the 1960s, for example, “housewife” was the default designation for women over the age of 16 (even though many had part- or full-time jobs). But the “housewife” would soon be replaced by the double-shift working woman, eternally “juggling” the demands of both home and work. By the end of the 20th century, now with the help of a fridge and a car, the daily walk to the local shops had been replaced by a weekly trip to the supermarket, where everything was available under one roof and the shopping was now a substantial task.

The first 1950s self-service stores are distant enough today to have become the subject of mild nostalgia, obscuring the original picture of smart efficiency. Black and white photos from the archives show people (particularly women) of every social type gamely learning to manage the curious “basket” containers provided for them to carry around on their arms and fill up as they walked around the shop. These shoppers are no longer standing or sitting at the counter while they wait for their turn and that, at the outset, was the visible difference introduced by self-service. What looks odd now, many decades later, is how little they’re buying – just a few jars and tins.

Save time online

With self-service firmly established to assist supposedly “time-poor” consumers, the stage was set for internet shopping to promise an even more efficient way of doing things.

An Ocado flyer from early 2019 displays the caption: “More time living, less time shopping”, as if living and shopping have become mutually exclusive. And crucially, it is not money but time – its saving or gaining – which is the quantifiable currency of the promotion.

In this way, the online upgrade appears to remove all remaining real-life interference from the task of shopping. You don’t have to take yourself anywhere to get to the store, which never closes. There are no empty shelves; everything is always there on the screen. There is still a trolley or basket, but not one that you have to push or carry, and it will hold whatever you “add” to it, irrespective of volume or quantity.

The shop assistant is wholly absent from the screen, although there are downgraded virtual versions available in the form of programmed chat-bots. With online shopping, the backstage work that “fulfils” an order occurs in a storage facility far away and is invisible to the customer. But in large self-service settings, like supermarkets and DIY mega-stores, the role of the checkout cashier had already been reduced to that single scanning function, requiring no specialist range of skills and no particular knowledge of any one of the thousands of possible things, from bananas to baby wipes, that they might be rapidly moving along.

Back to the ‘real’ shops?

Town centres had been dying a much discussed death for years, as more and more shops were being closed down – and stayed unused.

But amid the doom and gloom, some towns had been taking action to resist the trend, battling back with collective imagination and sometimes with significant financial backing. Shrewsbury Town Council revitalised a 1970s market building to make it a thriving centre for food stalls, cafés and specialist shops. The council also bought a couple of run-down indoor shopping centres in the town, which can now be redeveloped with community interests in mind.

On a smaller scale is Treorchy in South Wales, which won a national best high street prize in 2019 thanks to its flourishing independent shops and cafés. They all worked together to organise cultural events with the help of an enterprising chamber of commerce.

Still, initiatives like these were exceptional. For the places at the other extreme, where boarded-up units were everywhere, the call to keep shops open could sound like a hopeless plea, and too late to make a difference.

Lockdown’s impact

In the first weeks of lockdown, it seemed that the pandemic would hasten the move online, by closing down most of the shops that were left – and seemingly leaving online as the only option. But as that slow, strange time went on, it became clear that something quite different was going on. Two years later, we can see that the lockdowns brought about a return to slower, more local and personal modes of shopping.

The shops still open for normal business – those that officially qualified as providers of “essential” goods – were being used in new (and yet old) ways. They became places to go for some vital variation in our daily routines.

People also began to make a point of supporting and using independent, local shops. At the same time, home deliveries were being organised by these smaller shops, often working together in groups. This was the case with Heathfield, a few miles from Thomas Turner’s village in East Sussex. And it was nothing to do with the networks set up by the supermarkets and other big chains.

In the media, shop assistants, working on checkouts or filling shelves, began to be referred to as “frontline workers”. The implication of this “promotion” was that they were doing invaluable work that was comparable to the public-spirited dedication of NHS employees.

The local high street seemed to be benefitting from renewed appreciation. It was as if the pandemic had demonstrated what shops were really for, and why we should not let them go. To say that shops – real shops – are a much needed community resource used to sound worthy and well-meaning. Now it just states the obvious.

A return to home delivery

Meanwhile, another, related revival is happening: home delivery. This is often assumed to have been an online invention, promoted by big supermarkets as the latest expansion of their networks and by big stores of all kinds. Some of the big home delivery names, such as Boohoo and Asos, have no physical shops at all.

But until the middle of the 20th century, most shops offered home delivery as a matter of course. For many food products, like milk or meat, this arrangement was the default. The butcher’s boy brought round the tray of meat, and the milkman delivered the bottles direct to your doorstep every morning.

With self-service came the end of most home delivery services, too. When bigger supermarkets were built on the edges of towns, in the 1980s and 1990s, the basket became a big trolley, and people put all the bags they came out with into the back of a car. As with all the other changes associated with “self”-service, the difference was that customers were doing this work themselves. The “service” was no longer provided by others.

The new delivery services offered by smaller, independent stores that started up during lockdown represented a return to local arrangements of the kind that were standard before the arrival of self-service. Yet orders are often now made online. In this case, then, new technology has actively contributed to the revival of an older form of shopping.

In the East Sussex village of Rushlake Green, for example, the local shop began to offer home deliveries. This was so successful that they acquired a new delivery van with their name on the side. This marked something of a return to the 1930s, when local shops first started investing in a “motor van” to make deliveries (a new trend much remarked on in the trade handbooks of the time).

As it happens, this joining of the traditional with the latest tech is itself a long established phenomenon in the history of retail distribution. New modes of transport and communication have repeatedly modified the existing conditions of shopping, and the current manifestation has striking antecedents.

Virginia Woolf’s last novel, Between the Acts, offers a nice illustration of this. It is set at the end of the 1930s, when the installation of domestic telephones was beginning to make it possible for affluent customers to ring up the shop and order their meat or groceries for delivery, without having to leave the house or send a servant.

One scene in the novel has a country lady distractedly ordering fish “in time for lunch”, while she brushes her hair in front of the mirror and murmurs lines of poetry to herself. A few pages later, just as she requested, “The fish had been delivered. Mitchell’s boy, holding them in a crook of his arm, jumped off his motor bike.”

The narrator stays with this small domestic event for a moment, commenting on how the motorbike, a recent arrival on the local scene, is driving slow old habits out of use.

No feeding the pony with lumps of sugar at the kitchen door, nor time for gossip since his round had been increased.

In Woolf’s time, this mode of transport, along with the phoned-in order, was a notable innovation, allowing just-in-time gourmet food deliveries. Almost a century later, the exclusive telephone is now the semi-universal smartphone, but the method of ordering at a distance is the same. And as it turns out, the motorbike has not been superseded in the online age of Deliveroo.

For you: more from our Insights series:

The discovery of insulin: a story of monstrous egos and toxic rivalries

How your culture informs the emotions you feel when listening to music

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Rachel Bowlby does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.