The Bank of England has increased interest rates to 5.25%, a level not seen since April 2008 and markedly higher than the all-time lows of 0.1% seen less than two years ago.

In fact, interest rates hovered between 0.1% and 0.75% for the 13 years to May 2022. We are now in a new era in which the Bank of England – similar to other central banks – is using rate hikes (this is the 14th consecutive increase) to try to bring price inflation down from currently just under 8% towards its target of 2%.

The bank’s goal is to increase the cost of borrowing for retail banks, which then pass these costs on to households and companies. This reduces people’s spending and causes prices to rise more slowly as companies adjust to falling demand.

But interest rates are often called a blunt instrument because adjusting them to tackle inflation has an uneven effect. This is because people are at different stages of their lives and have varied levels and sources of income, not to mention debt.

So, there are winners and losers. Here are the main factors that influence how rate changes could feed through to your finances.

Do you have a mortgage?

Perhaps the most obvious impact of rising interest rates is increased mortgage repayments. This tends to affect younger generations (but not the youngest) and those in the middle of the wealth distribution the most. Higher interest rates lead to a fall in spending among these groups that is greater than the increase in their mortgage costs, which is what the bank wants to encourage.

However, the worst is yet to come for UK mortgage borrowers. Back in 2008, the bank started cutting interest rates to support the economy after the global financial crisis. At this time, the fee for ending a mortgage deal early to switch to a lower interest rate was often outweighed by the savings gained from the lower rate.

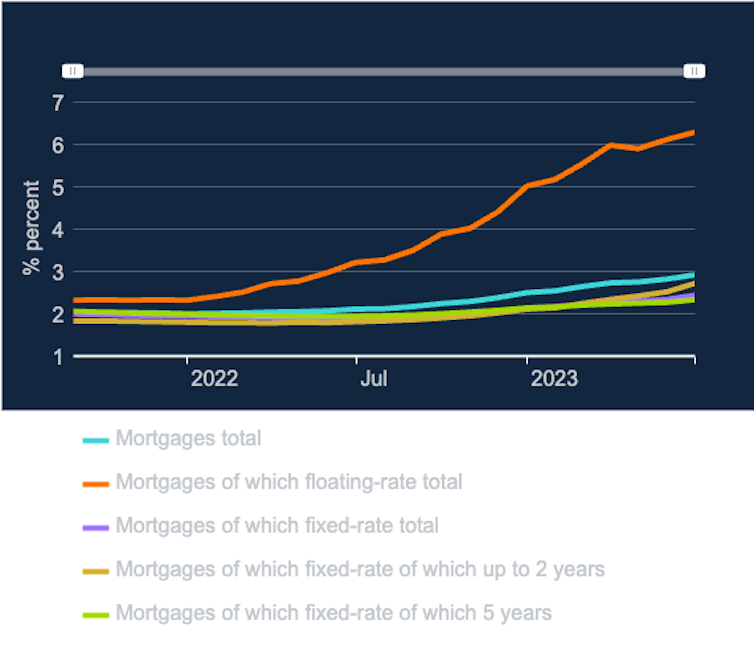

As more borrowers have been on fixed-rate mortgages as a result, people’s actual rates have risen much more slowly than the advertised rates for new mortgage deals. This chart, which includes all current UK mortgage deals, shows that rate rises have so far largely only affected variable- or floating-rate deals:

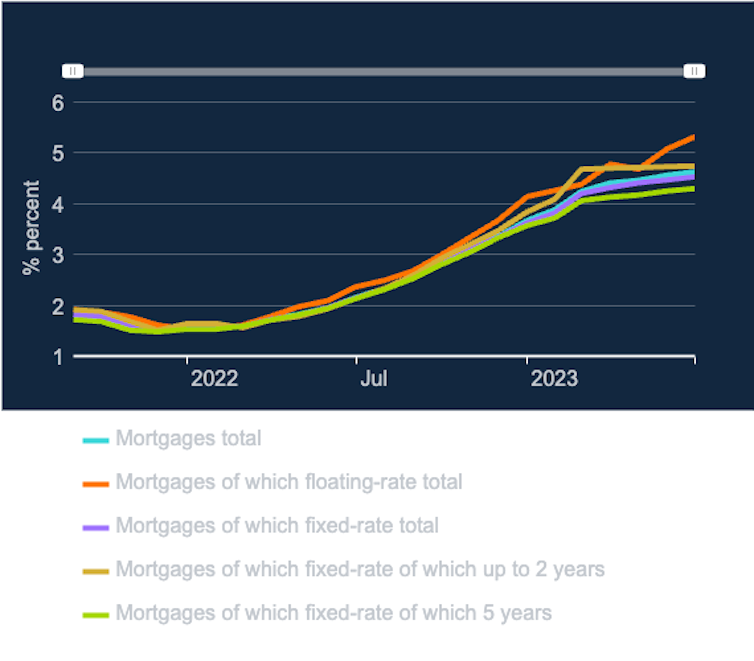

In contrast, this chart, which includes only new mortgage deals agreed since August 2021, shows how interest rate rises are similarly affecting repayments on all types of new deal:

As rates rise, only those who have to refinance will choose to move to a new loan, so the effects are likely to filter through at a slower pace. But it will happen – the 4 million borrowers expected to move to new mortgage contracts over the next three years could pay up to £220 more a month because of the current higher-rate environment.

Do you own your home outright?

House prices are widely expected to fall in coming months as rate hikes make it more difficult to get a mortgage – but this will only affect people who want to buy or sell. While your house may be worth less, if you remain living in it you still get to enjoy your home regardless of its price.

However, a house can also be a valuable source of collateral or security for repayment of a loan, so lower house prices can mean less opportunity to borrow in difficult times. This is particularly important for older generations who may need to pay for long-term care.

Do you have a pension or savings?

On the other hand, older generations (and wealthier households) may benefit from higher rates because they’ve had more time to accumulate wealth.

Rate hikes can boost returns on savings and fixed-income assets such as bonds and annuities (which provide a fixed income stream in retirement). For example, a typical 65-year-old looking to purchase an annuity with a £100,000 pension could get up to £7,352 per year now, compared with £4,786 at the start of 2021.

On the other hand, higher interest rates can make investing in the stock market less attractive. Reduced spending by the public means companies make less money for shareholders.

Do you rent your home?

The cost of living crisis, competition for rental properties and lack of supply of housing has led to a significant increase in costs for renters. But are they winners or losers when it comes to increases in interest rates? The picture is mixed.

Landlords may initially pass higher mortgage costs to renters. But, as more landlords exit the market, lower house prices could eventually cause rents to fall, as landlords need less to cover mortgage repayments. In the medium term, evidence suggests that higher interest rates ultimately reduce rents.

However, renters tend to be younger, less well off, and often living paycheck to paycheck, which is more likely to leave them worse off overall.

Do you live paycheck to paycheck?

A rise in interest rates tends to mean that things become more expensive, so people spend less and companies are unable (or don’t want to) pay workers enough to match the rise in prices. So, if even your take-home pay stays the same (or even goes a bit higher), the amount of good services you can buy with your wages falls.

This probably adversely affects those on lower incomes the most. The last time there was a major increase in interest rates in the 1970s, earnings losses from low-income households were many times that of high-income households. And when we consider the effects of lower incomes on spending, the gap between richer and poorer households is even greater. This is because people with no savings cushion are forced to reduce their consumption when prices rise. Around a third of UK workers are currently in this category.

On the other hand, the wealthy can draw down savings – including savings built up during the pandemic – and continue to spend.

Understanding and measuring the varied impact of rate changes in the current era of increases is crucial. This should be a top priority for economists and policymakers who want to achieve stable price inflation and grow the economy, while also protecting the most vulnerable.

William Tayler does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.