A remarkable archaeological find is likely to shed new light on a key aspect of the origins of Stonehenge.

The area around the world-famous prehistoric temple had almost certainly been continuously or intermittently regarded as sacred for thousands of years before the great stone monument was built 45 centuries ago.

Archaeological investigations, carried out just 100 metres north of Stonehenge back in the 1960s suggest that a series of giant totem-pole-like timber obelisks had been erected there some 5,500 years before the famous stone monument had been built.

But only the holes where the probable wooden obelisks had once stood have ever been found – and archaeologists therefore had no idea what the Stone Age ‘totem poles’ might have looked like.

However, investigations some 28 miles north-east of Stonehenge have now revealed a large fragment of a decorated timber monument which might provide clues as to what the pre-Stonehenge ‘totem poles’ may have looked like.

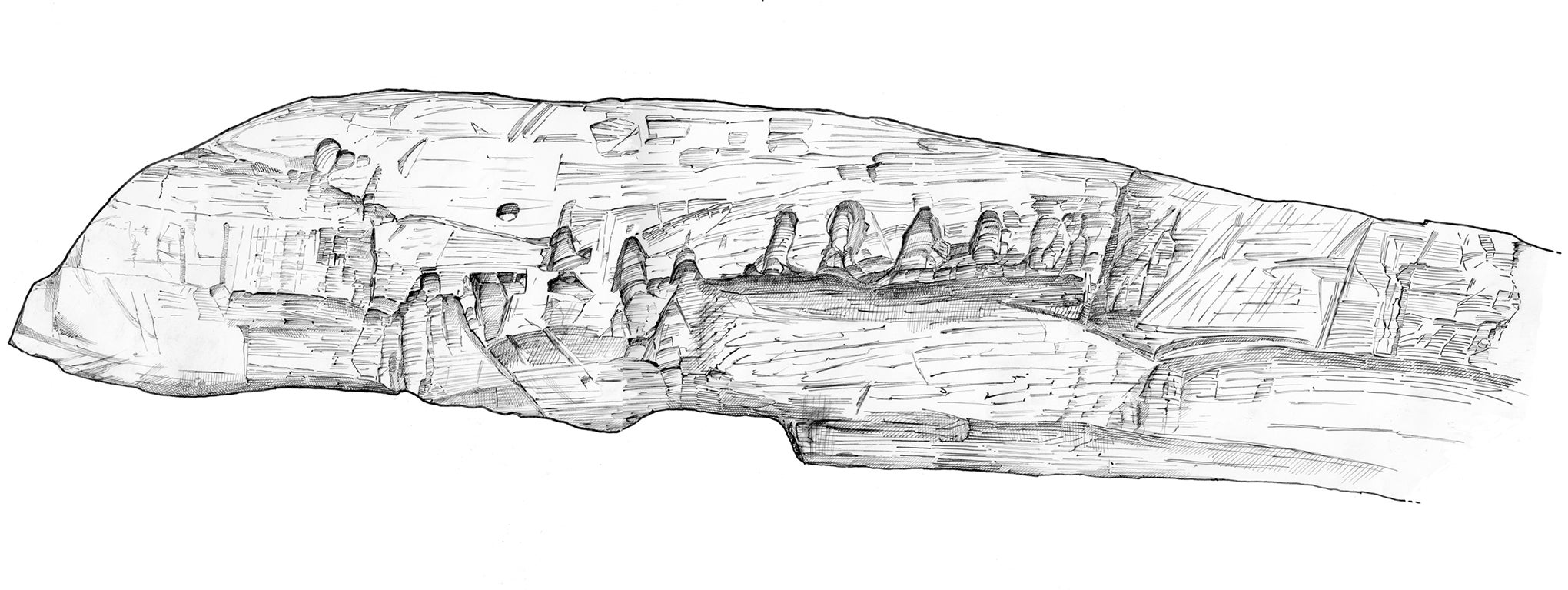

The metre-long fragment (originally probably part of a large decorated wooden obelisk or other structure) was only very recently radiocarbon dated – and has been shown to be the oldest decorated wooden object ever found in Britain.

Discovered near the Berkshire village of Boxford, it was made around 6,640 years ago and therefore dates from the same Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) era in which the Stonehenge area probable ‘totem poles’ were made.

It was decorated with a series of parallel line incisions, similar to that used in the earliest known prehistoric British pottery.

The only other known example of a British Mesolithic decorated wooden ‘monument’ is from South Wales and has roughly similar decoration.

Both the Boxford and South Wales monumental decorated timbers were preserved because, in prehistoric times, they had been placed (possibly deliberately) in wetland environments. The Boxford example was found 1.5 metres down in waterlogged peat, while the South Wales example was discovered in what had once been an ancient watercourse.

It’s conceivable that both had once stood upright as highly visible wooden monuments – but had eventually been placed in watery final resting places as offerings to nature spirits or ancestors.

Very little British Mesolithic art has ever been found – but the few examples that have been discovered are all seemingly abstract or symbolic (mainly consisting of parallel lines and geometric patterns). That’s in contrast to the continent where much Mesolithic art portrays people.

Some of the British wooden obelisks were very large.

The three Stonehenge area ones were each three-quarters of a metre in diameter – and probably stood around eight to ten metres tall.

The Boxford timber (of which potentially up to half survives) was much smaller – perhaps around two to three metres tall (and may have had a bifurcated ‘double-horned’ top), while the Welsh example was around two metres tall.

However, the world’s largest surviving Mesolithic timber monument – a giant highly stylized statue from central Russia – is five metres tall and, dating back 12,000 years, is the oldest decorated wooden object in the world.

The Boxford decorated timber was discovered by a local landowner, Derek Fawcett, a retired urological surgeon, during the construction of a workshop.

“It was a rather surprising find at the bottom of a trench dug for foundations. It was clearly very old and appeared well preserved in peat,” said Mr Fawcett.

“This exciting find has helped to shine new light on our distant past,” said Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England.

The Boxford timber – one of only two such Mesolithic decorated wooden objects ever found in Britain – is now being conserved at Historic England’s science facility in Fort Cumberland in Portsmouth.