Almost as much as actually playing the things, an important part of loving videogames is often being part of the communities that grow up around them. Indeed, finding a way to discuss this shared passion with strangers plays a major part in many of our formative online experiences. That might mean scrolling through social media or comment sections, or lurking on a forum or even – for those of us of a certain generation – a bulletin board. While its story might take place in 2003, Videoverse speaks to a more universal experience by being set in its own digital world, one that exists separately but adjacent to all these real virtual spaces.

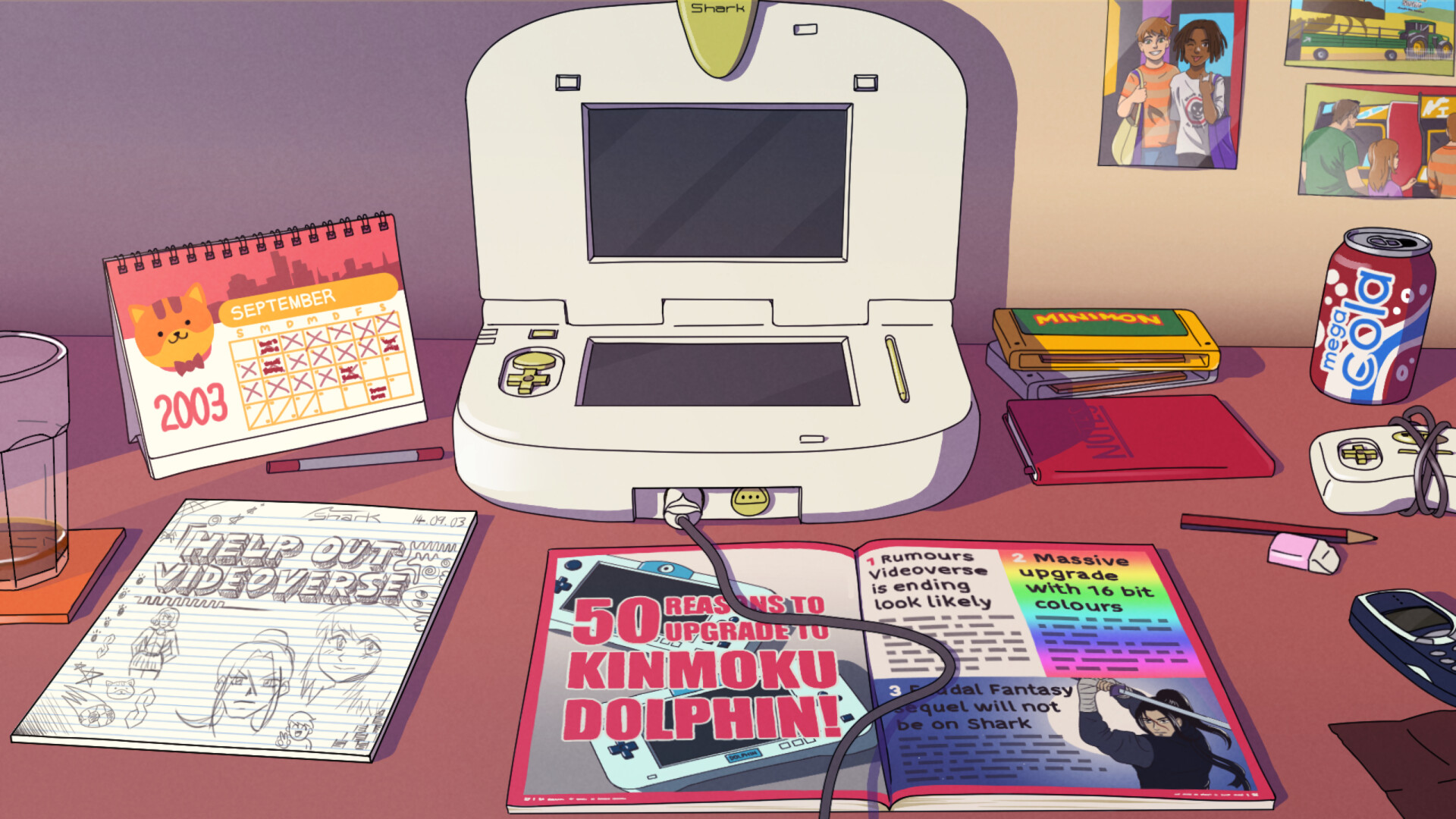

You're cast as 15-year-old Emmett, a big fan of the Kinmoku Shark gaming system, and in particular its killer app, Feudal Fantasy, an epic historical JRPG about warring ninjas. As a result, you're a regular visitor to the console's built-in social network, Videoverse. But with the forthcoming release of a new gaming system, Kinmoku's hardware is facing obsolescence – and along with it, so is Emmett's online community. That's more or less the story of Wii U's long-extinct Miiverse, of course, yet Videoverse's pixelated, lofi presentation is more a throwback to AIM, MSN, Bebo, MySpace, and other fallen Internet giants of old.

Old schooling

Given these nostalgia-inducing reference points, we're unsurprised when the game's developer, Lucy Blundell (working under the alias 'Kinmoku'), reveals the name of the project out of which Videoverse grew: Memories. Begun in 2017, alongside work on the console port of Blundell's debut One Night Stand, Memories was to be a "semi-autobiographical" story of a young woman reflecting on her life. She wanted the story to handle heavy topics including bullying and the character's journey towards discovering her asexuality. (Blundell herself identifies as grey-asexual.) Beyond that, though, there were many forms the game might have taken. At first, Blundell thought the young woman could be returning to her family home, old belongings conjuring up moments from her past. Another version was more conversational, having the character talking with a therapist. "I realised I was kind of finding myself whilst I was making this game," she reflects. "Because of that, it kept changing."

Meanwhile, there was a significant change in Bundell's own personal circumstances. "I got ill in 2019 and became disabled," she says. "It didn't stop me from working on the game, but it was in the back of my mind and, because I was ill, I didn't really work much that year." On top of this, when the COVID pandemic struck, Blundell realised: "'Oh, I'm telling a story that's quite heavy and sad.' I'm not saying there's no place for stories like that, but in me, I just felt I couldn't do it in this world. Everything felt quite bleak in 2020." Seeking a more positive approach, Blundell found inspiration in one aspect of this difficult period. "At the time, we were mostly communicating online, through Skype and Zoom. I thought, you know, the Internet gets a bad rap, but I think it's saving us all right now."

And so the work, ideas and personal reflections Blundell had gathered for Memories were redirected into Videoverse, with a new online focus. Particular influences on the game included virtual pet website Neopets and also Habbo Hotel, a virtual space allowing users to chat, play games and buy furniture for their rooms. (Both sites, despite their age, are still active today.) "The biggest one, really, was DeviantArt for me," Blundell says. "I kind of come from an artist background, and I was always drawing and uploading. I loved it and made some friends there."

Emmett likewise contributes his own fan art to the Feudal Fantasy forum, a place that draws on Blundell's experiences of online fandoms. "When I was really young I was into horse riding, so I was on horse-riding forums," she says. "Then I switched to Pokémon, Sailor Moon and Final Fantasy. I was on those for a few years. But the biggest influence for me was World Of Warcraft, because I was obsessed with it throughout university. It was pretty bad, actually – I had quite an addiction to it. A lot of the characters in the Videoverse are like people I met on World Of Warcraft."

Many of the game's chapters begin with Emmett playing snippets of the game before heading to the forums to scroll through posts and chat with friends, which is where rumours of Videoverse's shutdown first begin to circulate. The real-life parallels would be pretty clear, even without the title's nod, but they didn't inform Blundell as much as you might expect. "I was a casual Miiverse user, so I didn't use it that much," she says. "But I did love it. I loved its vibe. I loved its energy. I loved the shared drawings." These were Blundell's main interaction with Miiverse, joining the many users who posted drawings made with the Wii U hardware. Despite being an occasional visitor rather than a full-time devotee, Blundell "logged on for the last few days just to see what people were doing". She remembers the outpouring of messages celebrating and eulogising the platform. "The warmth and the heart of the community was coming out. It was nice to see."

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

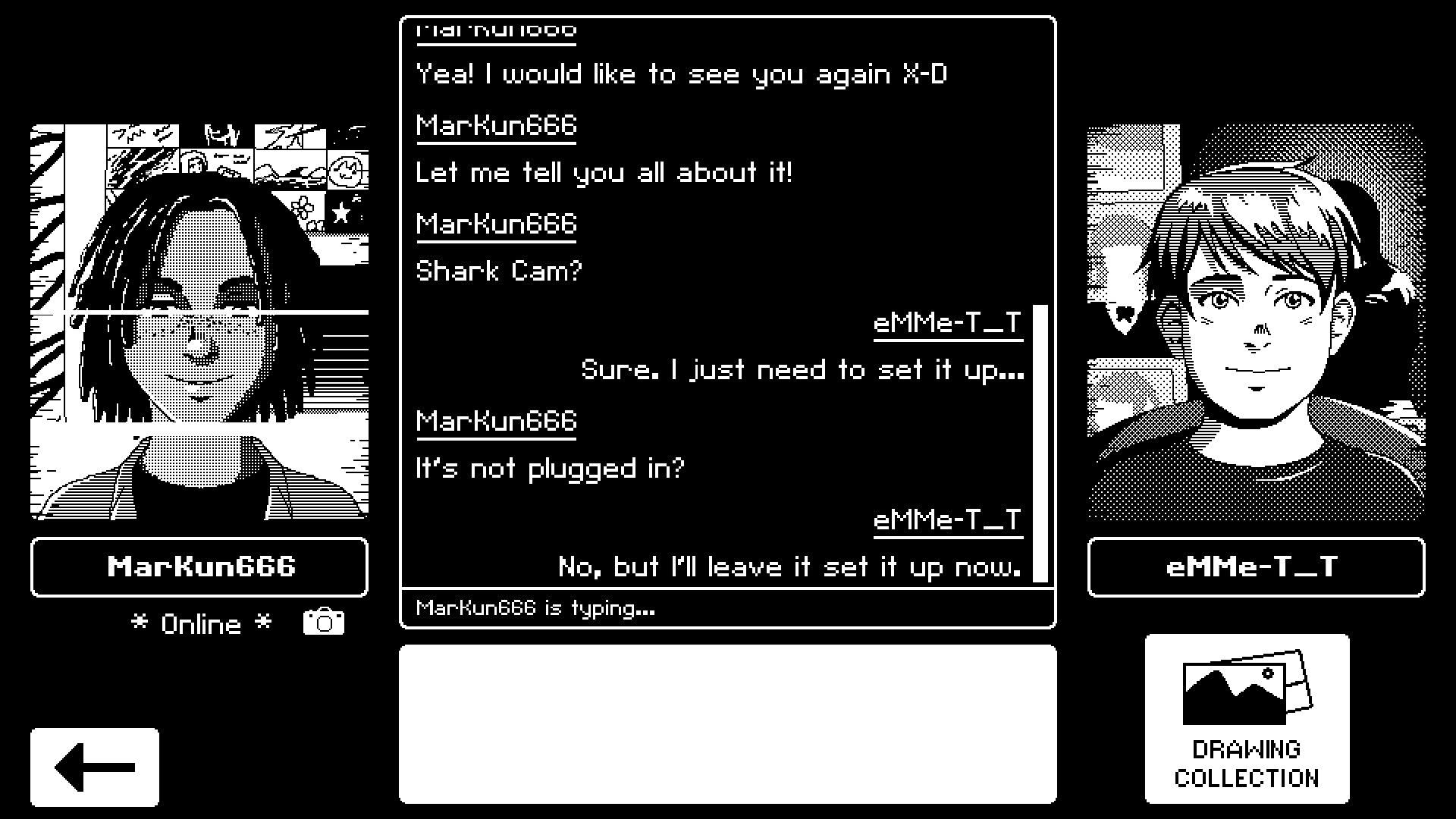

Miiverse might be long gone, but its legacy lingers – and not just in users' memories. The doodle-post feature was replicated in the later Splatoon games, while many of the actual posts have been archived on the website Archiverse, a resource that Blundell tapped when creating Videoverse's in-universe comments. "They boast 17 terabytes of posts, so it was a huge goldmine for me to pull out references." It's perhaps no surprise, then, that Videoverse feel so authentic, able to reflect our online pasts back at us with uncanny accuracy. That also applies to the aesthetics of the Shark console itself, with its big, chunky screen and two-tone visuals, not to mention the electronic whirs and the quiet buzz as the machine boots up (engineered by sound designer Alexandre Carvalho), along with the ambient soundscape (composed by Clark Aboud). Even the way Videoverse users type is nostalgic, with nonconventional spellings, weird flourishes of language, and complete disregard for capital letters that will be familiar to anyone who frequented the text chats of the era.

We can see ourselves in Videoverse, then. But ultimately we're playing as a tightly drawn character, Emmett, a 15-year-old who recently emigrated to Germany from the UK, something surely informed by Blundell's own experience of doing the same as an adult. For Emmett, at least, it leaves him feeling somewhat disconnected from his roots. "He looks for that kind of deeper connection online," Blundell says. "He starts very sweet and innocent and a bit anxious. He's a bit worried about uploading his drawings, but with the support of his friends, he's like, 'OK, I'll do it again'. In the end, he kind of gets over that hurdle, which is great. But he's also a character that the player can choose where they go with, so [one person's] Emmett won't be the same as someone else's."

There's no Dark Urge path here; whatever dialogue options you pick, Emmett remains a force for good, reporting mean comments and boosting other members of the Videoverse community. Yet his story can be taken in a variety of directions – as can the relationships he develops with other users online. Including, perhaps most notably, with Vivi, a new Videoverse user who Emmett first notices when she starts posting her own Feudal Fantasy artwork. After his supportive comments on her art, she reaches out over chat, and becomes almost as vital to Videoverse's story as Emmett himself.

While Vivi is shy and closed off at first, as she and Emmett get to know one other, we learn more about her: she's also 15 years old, living in London, and (naturally) a fellow fan of art and Feudal Fantasy, though not so much the combat. Over the course of the game the pair become close friends – or romantically involved, if you want to take it in that direction. Making both options available to players, and equally viable, was important to Blundell. "I love romance but I don't like forcing people to feel romance. I love that stuff, but not everyone else does," she says. "If you play platonic, in my opinion, you'll get a bit more out of it, because you don't [often] see male/female friendships in games. It probably added like another six months of work, or something stupid, because I kind of underestimated how much it would change. But it was worth it."

As the relationship between the two deepens – in whatever way you choose to take it – Emmett learns that Vivi is disabled, another way in which Blundell worked her personal experiences into the game. "At first, Vivi was quite unlikeable, because she was going through a lot of pain. She didn't really hide it. She didn't fake a smile, and it was almost like she didn't want to be there – which is kind of true. She wants to be out, like, living her old life. Vivi's story reflects very closely my own feelings about my newfound disability. My frustrations, the lack of understanding, and how, all of a sudden, you get treated as a lesser. You don't really realise how bad it is until it happens to you."

Blundell worked to soften Vivi, making sure players found the character "likeable". But her reactions to these new, difficult developments, as seen in the final game, seem similar to Blundell's own: the immediate confusion at the change of situation, followed by a feeling of helplessness. "You have this unknown of: 'Am I going to get back to my previous health, or is this it now?' I wanted that with Vivi. Like, how do you live with this? Sometimes you get a clear diagnosis – 'You'll be better in a year' – but sometimes it's not that clear-cut, and you just don't know." During this difficult time Vivi finds comfort in her friendship with Emmett, as the pair form a kind of support system that far stretches beyond a shared love for games. "Even if something really bad happens, you still have a future, you still have something worth living for, and I needed to make that for me," Blundell says. "I want [Videoverse] to be happy. Even though it has its heavy moments, I want it to be uplifting and happy, and to make people smile."

This, ultimately, is what all those real-life reference points bring to Videoverse. Their familiarity allows Blundell to tell an emotional, honest story of what these virtual spaces mean to us, and the very human friendships and support networks that can blossom because of them. If you're looking for evidence of how universally resonant these sentiments are, you need to look no further than Blundell's inbox, months on from the game's release. "I still get lots of nice messages and emails of people saying it touched them and they cried," she says. "And it's like, well, you're crying? Now I'm crying."

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.