What would a child-friendly city look like? One scenario goes like this: you wake up in the city one morning, there is no traffic, all you can hear are children playing and the occasional dog barking. All around you, muffling sound and covering dirt, is a magical material –- snow. It is malleable. It has endless possibilities. It turns hills into giant slides and you can build with it.

Snow days are, of course, temporary aberrations within urban life. As such, they are rapidly corrected by snowploughs, salt and gravel, or, in warmer countries, simply by the weather. Snow turns to slush, traffic returns, school resumes.

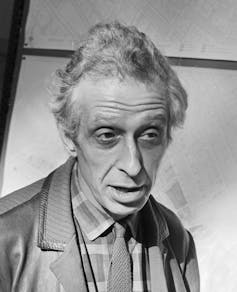

Another possibility was offered by the Dutch architect and playground designer Aldo van Eyck. Between 1947 and 1978, he designed and built around 700 playgrounds in Amsterdam. Sand, not snow, was his magical material.

The mid-20th century was a period of intense activity around play provision in western and northern Europe, as my research has shown. Aldo van Eyck put children and play at the centre of his humanist approach to modernism.

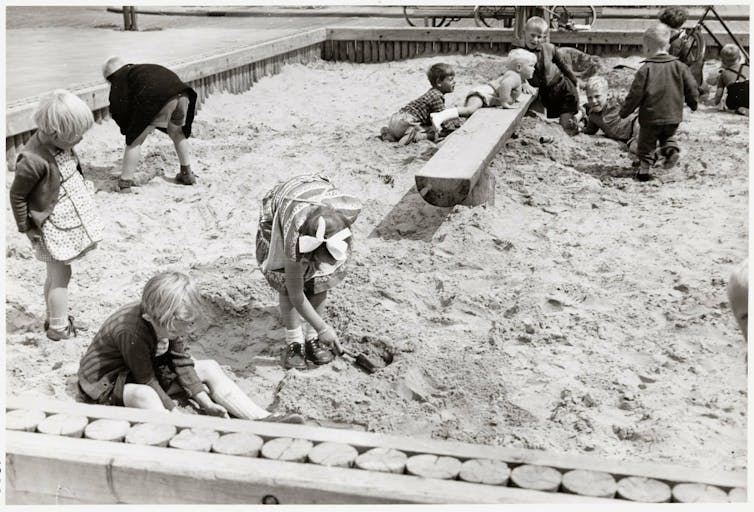

The magic of a sandpit

Van Eyck belonged to a generation of architects who were critical of the urban rationalism of the modern movement. They loved many modernist buildings but hated the sort of urban planning that went with them, whereby the city was arranged around zones of dwelling, zones of work, grids of transport and hubs of recreation.

By contrast, van Eyck and his peers wanted to humanise the modern movement. One way of doing that was to insist that children should be at its centre.

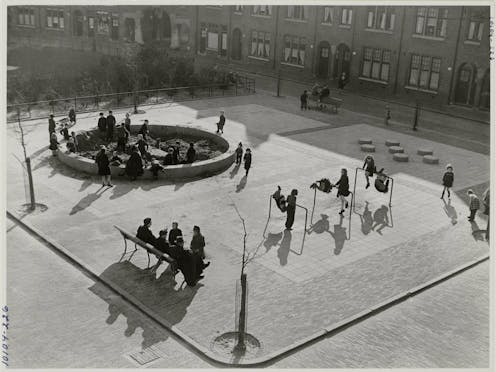

Most of the playground he conceived of were small, modest affairs. There was no showy paraphernalia, no zip-wires or intricate climbing frames. Very few of them even had swings.

Instead, they had low walls, benches, sand pits, stepping stones, simple sets of aluminium bars in the shape of rudimentary bridges, cones and what van Eyck dubbed “igloos”. The playgrounds weren’t fenced off from the rest of the neighbourhood.

Adults, with or without children, would stop there and read a newspaper for a while. Children would hang upside down from an aluminium bar or run along a low wall or jump from one stepping stone to the next.

At the centre, there was usually a sandpit, sometimes with concrete islands, and often filled with children.

Sandpits require vigilance and care if they are to avoid becoming harbingers of dirt and disease. They need to be cleaned, and cleared of any animal deposits, and the sand regularly changed.

‘A launchpad to the outside world’

Van Eyck thought of his playgrounds as “doorstep” playgrounds. But the doorstep wasn’t just a metaphor for the proximity that they would have to children’s homes.

Unlike the abstraction of “dwelling” as a concept, the doorstep was a physical reality. It was an actual step, that children sat on, while a parent talked to a neighbour. It could be a fort or a mountain. It was a bridge, too, between home and the street, between family and something bigger. It was the launch pad to the outside world.

Aldo van Eyck had joined Amsterdam’s Department of Public Works in 1946. By 1951 he had formed his own architectural practice but continued working for the municipality constructing playgrounds on a consultancy basis until 1978.

In 1961, the International Play Association was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. In 1974, Arvid Bengtsson, the Swedish landscape architect and then president of the association, published The Child’s Right to Play, in which he campaigned for playgrounds to be close to where children live.

Indeed, he wrote, they “should be within sight and hearing distance of home”. A city like Amsterdam needed 700 playgrounds to meet this target.

The playgrounds he established were built on neglected plots of land. Some of these were unloved bits of ground, the dumping grounds that every city has. Other plots had a more traumatic history.

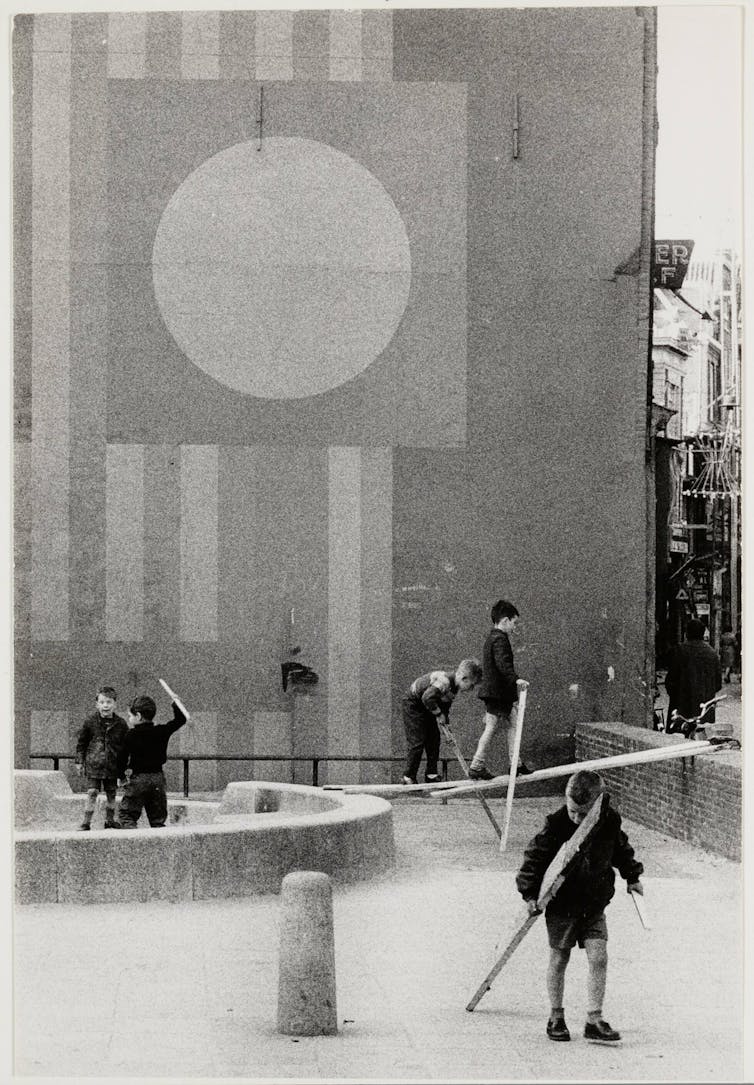

The 1956 playground in the west of Zeedijk, for instance, was built on the footprint of two houses that had once housed Jewish families who had been deported and murdered during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. The two homes had been dismantled by local residents looking for anything to burn to keep warm.

Today, only about 17 of Aldo van Eyck’s playgrounds remain. The one on Zeedijk, the street in the old city that runs along the boundary of the De Wallen neighbourhood, featured abstract murals by Joost van Roojen. Though it won awards when it was first built, it slowly fell into disrepair in the 1970s, when the area became an enclave for heroin addicts.

By the 1990s, nothing was left of the original Zeedijk playground design. Talking at the end of his life, van Eyck noted how these structures, that he had posited as so central to his vision of the modern city, had to be maintained if they were to survive:

An urban ingredient as vulnerable as playgrounds cannot survive without constant attention and special care.

Ben Highmore receives funding from Arts and Humanities Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.