Did Jacinda Ardern resign because Labour faces certain defeat in 2023? Elliot Crossan kicks off a three-part series on Labour's leadership transition.

Three parts: How Labour fell into crisis barely two years after its historic election win | Every chance at transformational change squandered | An uphill battle for Chris Hipkins

Opinion: “Tonight, New Zealand has shown the Labour Party its greatest support in at least 50 years. We have seen that support in both urban areas and in rural areas and seats we may have hoped for, but in those equally we may not have expected. And for that, I only have two simple words. Thank you.”

With these words, Jacinda Ardern began her victory speech on October 17 2020, the night Labour won more than half of the popular vote in a general election for the first time since 1946. It was their best result in 74 years – remarkably “at least 50 years” turned out to be a conservative estimate. Labour secured an outright majority – the first party to do so since proportional representation was introduced in 1996. The popularity of Ardern and her Government was unprecedented in the modern era.

The National Party in turn scored their second-worst result since they were founded in 1936. Leader Judith Collins said in her concession speech congratulating Ardern: "Three years will be gone in the blink of an eye. We will be back." At the time, this statement seemed wildly optimistic. National would be back, no one doubted – but in just three years? Really?

READ MORE: * Part 2: Every chance at transformational change squandered * Part 3: An uphill battle for Chris Hipkins * Election 2023 – it’ll be the economy again, stupid! * Labour’s electoral mountain remains as high as ever

Barely more than two years later, Ardern’s sudden resignation has shocked the country. She is the first elected Prime Minister since David Lange not to fight for – and win – a third term. Labour was already trailing in the polls, with National under new leader Christopher Luxon and their more extreme ACT Party allies the favourites to form what will be New Zealand's most right-wing government since the 1990s. Now Labour’s star leader is gone.

In an equally shocking twist, Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Grant Robertson, Ardern’s widely anticipated successor, then refused to take up the job vacated by his close friend and long-time ally. Both of Labour’s most able and charismatic politicians have thus ruled themselves out of the picture. Instead the competent but uninspiring Chris Hipkins has been chosen to lead his party into a tough election battle in nine months’ time.

Labour has fallen into crisis just 27 months after the biggest election landslide of any party in the modern era. How did it come to this?

2020 was always going to be high tide for Ardern

It was always clear 2020 was going to be the high tide for Ardern, and – for the foreseeable future at least – for the centre-left bloc as a whole. Together, Labour and the Green Party received 57.9 percent of the vote.

The 51.6 percent vote share received by Labour, the Alliance and the Greens in 1999, or the 48.6 percent won by National and ACT in 2008, pale in comparison – in 2020, Labour alone won 50 percent.

This result translated to 75 seats in a Parliament of 120 for the two parties.

Labour took a clear majority without even needing the 10 Green MPs to govern. The Greens were offered a reduced role in government in return for staying subservient to Labour.

In 2017, long-time kingmaker Winston Peters held the balance of power between National and Labour, and chose to make Ardern Prime Minister. Yet in 2020, the then Deputy Prime Minister Peters was removed from parliament altogether, with NZ First winning no seats after their lowest ever share of the vote.

The Covid landslide

The Ardern Government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020-2021 was masterly. Her slogan “go hard and go early” represented an elimination strategy that saved thousands of lives, perhaps tens of thousands. The contrast with how most other countries dealt with the virus was stark.

If, for example, Ardern’s Government had been as incompetent as Boris Johnson’s Conservative Government in the UK, which consistently prioritised reopening the economy over human life, the same per-capita death rate would have seen more than 16,000 New Zealanders killed by the virus instead of 2,500.

Johnson was alleged to have declared “let the bodies pile high" in late 2020. The difference between Ardern’s empathetic leadership and Johnson’s shocking lack thereof could not be more obvious.

This approach was undoubtedly worthy of support, and the majority of the voters clearly agreed.

The electorate rejected National’s calls to reopen the economy too early. Labour won over “middle New Zealand” in huge numbers, with Ardern borrowing many traditional National supporters amid the unprecedented crisis. Many swing voters, and even some conservatives, felt safer sticking with the incumbent Government’s approach to Covid-19.

The problem is that those voters were always unlikely to stick around for long once the pandemic was no longer dominating the news agenda. Relying on borrowed National voters to re-elect Labour in 2023 was a dangerous game, with little chance of success.

The cost of living crisis

Towards the end of 2021, a cost of living crisis began to hit with full force. Inflation over the past year has been at its highest level since 1990. Petrol and food prices have gone through the roof. The cost of rent, already exorbitant, is at its highest ever level.

This is an emergency for poor and working class people. Millions of New Zealanders were already struggling from paycheck to paycheck just to get by. Wages and benefits were already too low, housing costs already too high, and now inflation is hitting people where it hurts.

Contrary to the protestations of Christopher Luxon, this cost of living crisis has not been caused by Labour spending too much money. Economic crises (pandemics included) require the state to spend money – and National should know that. Government spending reached similar levels after the Global Financial Crisis, when John Key was in power.

The consensus among most economists is that the global inflation spike has been caused by the war in Ukraine, supply chain issues resulting from Covid-19, and the vast sums of money accumulated by the super-rich during the pandemic.

Jacindamania inevitably began to wane — though Ardern remained the country’s preferred Prime Minister.

So what did Labour do to address this emergency scenario? In March 2022, the Government announced it would temporarily halve public transport costs, and reduce fuel tax by 25c per litre. Then in the May Budget, its big opportunity to deliver a significant and meaningful response, Labour extended its March package by two months, and introduced a payment of $350 over three instalments to people earning under $70,000 a year. With food costs rising by 11.3 percent by the end of the year, this was nowhere near enough.

Inexplicably, it refused this payment to beneficiaries and pensioners who were already receiving the annual Winter Energy Payment – meaning the poorest people who needed the most help with the increased cost of living would not be given anything extra at all. The Green Party’s Social Development spokesperson Ricardo Menéndez March put an amendment to include beneficiaries in the cost of living payment, which Labour voted down. This was despite a poll showing two-thirds of the population were in support of including beneficiaries and pensioners in the package.

National was able to claim that Labour were spending too much and that the inflationary crisis was the result; yet for ordinary people feeling the pinch, little of that supposed spending was noticeable. Under Luxon, the Opposition surged in the polls at Labour’s expense, without National or Luxon having to perform particularly well in the media or offer much in terms of policy.

Labour’s Covid honeymoon ended in late 2021 as people grew sick of the final lockdown and inflation started to bite. Jacindamania inevitably began to wane – though Ardern remained the country’s preferred Prime Minister. National took a narrow lead in the polls in 2022. But defeat for Ardern was far from inevitable.

A close election?

It is certainly not a good sign when a governing party loses about a third of its supporters in a couple of years.

From winning 50 percent in their 2020 landslide victory, Labour fell to an average of 36 percent across all polls in the first half of 2022, and 33 percent in the second half of the year.

However, while it is remarkable how far and how fast they have fallen, it is actually normal for a government to be behind in the polls mid-term.

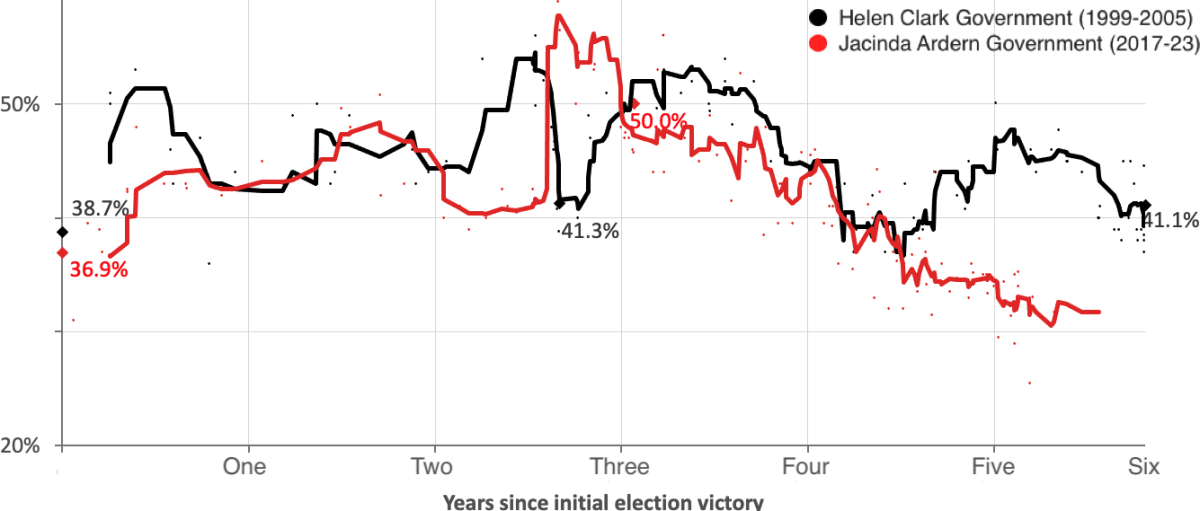

NZ Labour polling: Helen Clark v Jacinda Ardern governments

Helen Clark faced a similar slump in Labour’s polling in 2003-2004. The problem for the current Labour Government is that, while Clark was able to recover some ground within the space of a year, the Ardern Government continued to slide further in the polls. Labour’s worst polling result of 1999-2005 was 36 percent; Labour’s current polling average is 32 percent, with three recent polls putting them below 30 percent.

However, Labour’s vote share alone doesn’t show the full picture. The clearest metric of who is on course to win the next election is to add together the centre-left and centre-right parties and compare them directly.

Ardern would have been the perfect leader to make Luxon crumble in an election, as she is everything he is not — charismatic, likeable, self-aware, in touch with the public, and at her most inspiring on the campaign trail.

Labour’s polling alone is certainly not promising, but when looking at the bigger picture, it is very close. Labour, the Greens and Te Pāti Māori together only fell behind National and ACT three months ago, and even then, the gap is only in the single digits. Opposition parties usually perform better mid-term, and generally speaking, governments tend to regain support as election day gets closer.

Then there are the preferred Prime Minister ratings to consider.

Ardern’s popularity equalled Bill English’s support very quickly during the 2017 election campaign, then soared ahead once she became Prime Minister. Luxon is certainly more favoured than the three National leaders who preceded him, but he is not currently as popular as English, let alone the all-conquering John Key, who after his first four months as Leader of the Opposition saw the National Party lead every single poll until he resigned nearly 10 years later.

Luxon is a political lightweight. He was a relatively obscure figure until being parachuted into the job of National leader in November 2021. He has been hyped up by the media at a time where Labour’s support has been waning. But he is not a charismatic person; he does not have the killer instinct or the talent for theatre that Key had.

In policy terms, National are not offering much, and nothing new: tax cuts which will benefit the already wealthy and barely do anything to help workers struggling with inflation; platitudes about how they will grow the economy and be “tough on crime”; promises to attack beneficiaries. All this will do is make the rich richer while attacking the working class.

Ardern would have been the perfect leader to make Luxon crumble in an election, as she is everything he is not – charismatic, likeable, self-aware, in touch with the public, and at her most inspiring on the campaign trail. She has star power in spades. But we won’t now get to see what Ardern would have been like in the 2023 election – nor what the fiery debate-master Grant Robertson would have done in her place.

Series continues: Ardern squandered her chance at transformational change at every turn | An uphill battle for Chris Hipkins