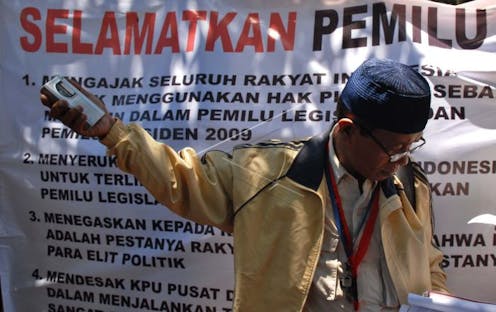

Indonesian politicians backing President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo have come up with the idea to postpone the next presidential election, slated to be held in 2024, and enable the president to serve a third term.

The politicians, all affiliated with the ruling coalition, and Indonesia’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, claimed that there were big data containing aspirations from social media users who demand the election postponement.

The term big data now has become a buzzword used by many people in the country.

With the rapid development in communication and information technology, politicians and government officials often misuse the term big data to push their political agendas, including those that violate the Constitution.

Misuse of “big data” term

Many politicians use the term Big Data to look up-to-date and technologically savvy to the public without understanding its concept.

Many assume that Big Data is only about the size of the data, as if when I have a massive amount of data, then I have Big Data.

In some cases, that might be true, but not in most cases.

The term Big Data generally refers to large and complex datasets in various formats, either structured, unstructured, or semi-structured ones.

IT experts and data scientists typically define Big Data by using 3V: Volume, Velocity, and Variety.

Volume relates to the data size (in Tera or Zettabyte sizes) collected from various devices and applications. Velocity refers to how fast the data is produced and processed to extract meaningful information. Meanwhile, Variety deals with the kinds of data formats, whether structured data (e.g. relational databases) or unstructured data (e.g. videos, texts, or posts in social media).

In recent years, many scientists have agreed to add more Vs to be able to define big data properly. Thus, many have used 5Vs (or even 6Vs, and so on), with two important factors included: Value and Veracity.

Value deals with how information, knowledge, and patterns in the data can be extracted to accelerate business processes, while Veracity deals with the accuracy and trustworthiness of the data.

If we talk about data in social media, Veracity appears as the most fundamental factor to consider, because it deals with the trustworthiness, accuracy, authenticity, and accountability of the data. While in fact, in social media, everyone can write, post, and share any information without thorough verification.

Creating an account on social media is very easy. People can make multiple accounts and share the same information numerous times. Consequently, conclusions made from data distributed in social media can be full of bias or partisan.

Big data cannot represent the people’s voices

There are at least four reasons Indonesia should not base its election planning on big data.

First, analysis of big data, especially when it is taken from conversations on social media, has been widely used to predict election results. Yet, the results have not consistently matched the voting results, as what happened in India, Malaysia, and Pakistan.

Second, many conversations on social media in Indonesia are driven by cyber troops who spread pro-government propaganda. During the 2019 general election, many cyber troops spread fake news to amplify political taglines and hashtags.

Therefore, analysing conversations on social media is not only about collecting the data but also about “cleaning” and ensuring its integrity.

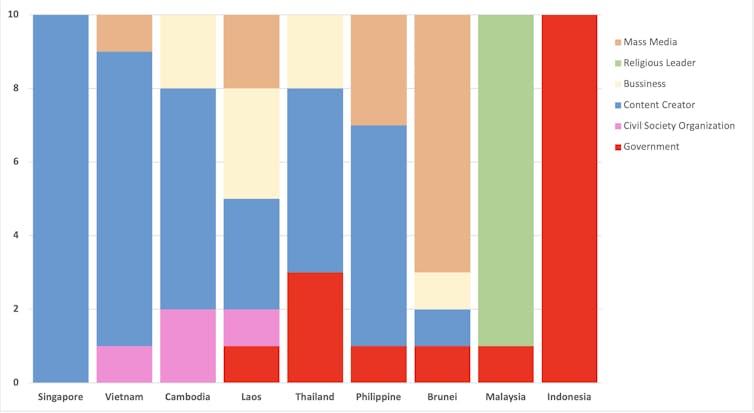

Third, and most importantly, conversations on social media are dominated by government-led narratives.

My research about the narratives of COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asian countries has shown that in Indonesia, narratives about the pandemic are dominated by the government authorities from various levels.

In Indonesia, posts from government accounts, such as the Facebook pages of President Jokowi, ministries, state bodies, and regional leaders, got the most engagements from social media users. The entire top 70 posts were from government-controlled accounts.

But the engagements obtained by the accounts were only in passive forms, such as through likes or reactions. Thus, such a predominance does not necessarily mean that the public really gets information from the government. Passive engagements usually come from ads placement on Facebook.

Compared to civil society organisations, government institutions certainly have larger resources to advertise their content on social media.

Fourth, although many policy designs and implementations are concluded from big data analysis, the policies still have to reflect public values.

The idea to postpone the 2024 election based on people’s aspirations on social media has denied the participation of people who do not have access to social media and, thus, undermines public values of trust, equality, and fairness.

Therefore, people should be more careful before making conclusions from what appears on social media. We need to ensure whether the data are genuine, accurate and trustworthy – which can be done using the 5V formula.

We should not use any term to follow a trend or be seen as technology-savvy without truly understanding its meaning.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.