In the moments after he lost to Jimmy Young in 1977, George Foreman vomited. His sweating body shook uncontrollably. In the dressing room, Foreman climbed a table and leapt from it; he later said he’d heard God talking to him.

The match, held on a humid March night in San Juan, Puerto Rico, had been a stunning upset that “traumatized the heavyweight boxing scene.” But for the Texas boxer, its aftermath offered a new start. “With his championship aspirations dying,” sports historian Andrew R.M. Smith writes, “Foreman started to come alive again.”

When he arrived at the hospital, doctors said Foreman suffered from a concussion and heatstroke. He spent a day in the ICU. But by breakfast the next day, Foreman had checked himself out. “It made everything clearer for him,” Smith writes of the near-death experience. At just 28, Foreman—the man who once said “boxing was invented for me”—left the sport that had taken him from poverty to the Olympics and becoming the heavyweight world champion.

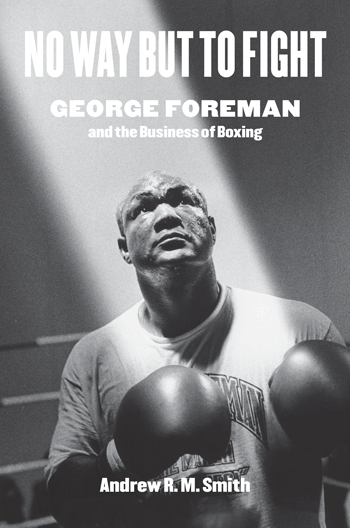

Both as a boxer and a person, the 1977 loss transformed Foreman. Smith chronicles that evolution, and the many others in the athlete’s life, in his fascinating, colorful new biography No Way but to Fight: George Foreman and the Business of Boxing.

“During that half century of public life,” Smith writes of Foreman, “the most consistent aspect of his career remains the ability to adapt and reshape his image.” Over 15 well-researched chapters—which include interviews with Foreman and materials gathered from archives across three countries—Smith chronicles that resilience.

Foreman was born in 1949 in the northeastern Texas town of Marshall. There, his mother and father lived in a shotgun house without rooms, appliances, plumbing, or electricity. One of seven children, George was six months old when the family moved to Houston, following the family patriarch, J.D. Foreman, and his job working on the Southern Pacific Railway.

The Foreman family mirrored Texas’ demographic change. In 1900, more than 80 percent of the state’s African American population lived in rural areas. Fifty years later, 65 percent of African Americans in Texas lived in urban areas. The Foremans moved to Houston’s Fifth Ward, a rough area nicknamed the “Bloody Fifth.” Young George supplemented the money he earned from washing dishes at a local restaurant by robbing people of theirs.

As an adolescent, Foreman seemed headed to prison after he dropped out of junior high and started shoplifting and getting into fights. “He became a statistic,” Smith writes of Foreman, “just at the moment when such statistics mattered to policymakers.” In 1964, as part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s war on poverty, the Job Corps was founded to provide basic education and vocational training. The program took Foreman from the Bloody Fifth to Oregon and then California, where he learned carpentry, bricklaying—and boxing.

In the 1968 Olympics, Foreman stayed notably apolitical, distancing himself from Tommy Smith, John Carlos, and other U.S. athletes who protested apartheid. While Smith and Carlos raised their black glove-covered fists on the medal podium, Foreman celebrated his gold more quietly, waving a small United States flag. “I just do my own thing,” he said after his victory. “I am no Uncle Tom.” That was the Foreman who became popular with politicians—the Foreman who would meet for photographs and handshakes at the banquets of those politicians who promised to continue funding his beloved Job Corps. When a representative of Richard Nixon approached Foreman seeking his support, he declined because the Republican presidential nominee planned to defund social programs.

There was the George Foreman who became a prize fighter and, especially after defeating Joe Frazier and Ken Norton, appeared invincible. When he fought Muhammad Ali in the famed 1974 Rumble in the Jungle, most assumed Foreman would leave Kinshasa, Zaire, undefeated. Oddsmakers had Foreman as a three-to-one favorite. When Ali won, Foreman scrambled for answers. An existential dread accompanies every loss a boxer faces, a feeling only intensified by an upset to the undefeated heavyweight champion of the world. “I felt as if my core had evaporated,” Foreman said of the loss. Less than three years after losing to Ali, there was the Foreman who abruptly retired, became an evangelical minister, and even went back to where it all began to fall apart. “He returned to Zaire to preach instead of punch,” Smith explains.

And, finally, there was Foreman the comeback story. A decade after he retired, he returned to the ring. An old man by the standards of professional athletes, he was noticed by many but taken seriously by few. Foreman—once described by Norman Mailer as a “catatonic menace”— had changed. He smiled and joked. No longer the muscular 20-something who looked to have the perfect physique for boxing, the overweight Foreman was self-deprecating. Remarkably, two decades after losing boxing’s heavyweight world championship, he regained it. At 45, Foreman jokingly thanked “all [his] old buddies in the nursing home” as soon as he won. “[I] exorcised the ghost once and forever,” a serious Foreman said of that loss in Zaire that haunted him.

That’s the Foreman closest to the one many recognize now: The grandfatherly pitchman who made a fortune selling a moribund grill that came to life once it had his name on it. Previously marketed as the Fajita Express, the product had been a flop, but the rebranded “George Foreman Lean Mean Fat Reducing Machine” went on to sell more than 100 million units. “Foreman’s royalties escalated to millions of dollars a month,” Smith explains of the ’90s kitchen staple’s incredible success.

For a state best-known for its football talent, Texas has also given birth to great boxers. Their stories show that boxing has always been a poor man’s sport. Among the best were Jack Johnson from Galveston, Curtis Cokes from Dallas, and Orlando Canizales from Laredo. But out of all the great boxers from Texas, perhaps George Foreman best represents contemporary society.

From an era when boxing’s influence reverberated across the United States and the globe, to when Foreman became better known for his infomercials than what he accomplished in the ring, No Way but to Fight uses the boxer as a lens to show a changing society. Smith emphasizes Foreman’s ability to reshape and adapt his image while also noting the athlete’s complexities. He writes of a boxer who ultimately triumphed in the most unvirtuous of sports. By what he accomplished inside the ring, Foreman built an empire outside it, ensuring “his descendants won’t have to fight in the same way.”

READ MORE:

-

What’s in a Name? New lawsuits by transgender people challenge bans on name changes for those convicted of crimes.

-

17 Great Books on the Border to Read Instead of ‘American Dirt’: There’s no shortage of talented Latinx writers with all kinds of stories to tell. Let’s make space for them.

-

He May Not Be a Candidate, but Beto O’Rourke is Rebuilding His Texas Organizing Machine for 2020: O’Rourke’s 2018 Senate campaign was fueled by an organizing network of 20,000 volunteers. Can he harness that energy again without being on the ticket?