The UK’s House of Lords has existed in one form or another since the 11th century, making it one of the oldest political institutions in the world.

However the Lords is an unelected house, which raises questions about what place it can have in a modern democracy. These have flared up with new vigour in the wake of former prime minister Boris Johnson’s resignation honours list, which contained multiple surprises. Among them a peerage for his former special adviser, aged just 29; and for two politicians currently facing allegations of wrongdoing.

And beyond the content of the list, there is the question of whether Johnson, who was ousted from office following a string of scandals, should have been allowed to appoint anyone at all. The same could be said of his successor Liz Truss.

With close to 800 members, the House of Lords is the second largest legislature in the world (behind only the Chinese National People’s Congress). It’s actually smaller than it used to be before the government of Tony Blair reduced the number of hereditary peers, who inherit seats as a supposed birth right. Labour’s reform was aimed at refocusing on life peers – members of the House of Lords who are appointed based on merit so that they can contribute their specialist knowledge to debates, for the betterment of the laws passed.

Currently, peers can claim a £342 tax-free allowance for each day they attend, plus eligible travel costs. While more recent data is skewed by the pandemic, in 2019/2020, £17.7 million was spent on Lords allowances and expenses, with peers claiming an average £30,687 in that roughly 12-month period.

The absence of elections to the Lords, combined with its size and cost, makes the public perception of how people are appointed even more important.

Routes to the Lords

There are several ways to become a member of the House of Lords.

Prime ministers leaving office can recommend peerages in their resignation honours list for people who have supported them. Peerages can be awarded to MPs who are leaving the House of Commons at the end of a parliament, in what is called the dissolution honours. Speakers of the House of Commons are traditionally given a peerage, too – although John Bercow was the exception.

Between these regular events, peers can be appointed via “political lists” or as “working peers” to boost the strength of the three main parties – all of which are constantly seeking to ensure that none has an overwhelming majority in the Lords. Governments can also make ad-hoc appointments to give someone a peerage so that they can become a government minister.

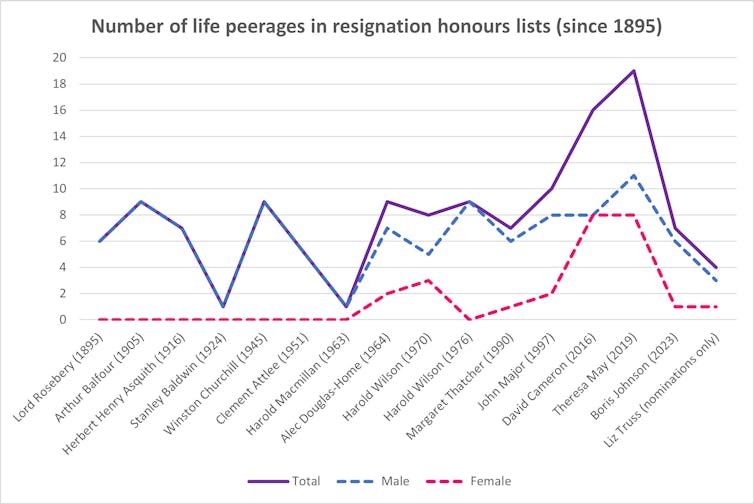

Historically, the most controversial of these routes have been the political and resignation honours lists – primarily because of perceptions of cronyism. This has not been helped by successive prime ministers adding more and more names to their resignation lists.

The appointments commission

In 1917, a resolution was passed in parliament stating that prime ministers should give their reasons for recommending someone for a peerage and be sure to have “sufficiently satisfied himself” that it is not connected to the promise of party funding.

The practice of rewarding those who contribute party funding dates back to at least the 15th century. Unfortunately, it still happens today.

What has changed are attempts to make the process appear transparent. Since 2000, the independent House of Lords Appointment Commission has advised on the process, insofar as it recommends people for appointment as non-party-political (cross-bench) life peers. These positions are for people with life or professional experience that can add expertise to the House or who are chosen to help ensure the chamber reflects the diversity of the wider public.

The commission also has a role to play in vetting other nominations for propriety, including political appointments with a view to minimising potential reputational risks for the house. The commission is not involved in the appointment process after providing that advice to the prime minster.

Johnson took the unprecedented step of ignoring the commission’s advice in 2022 when he appointed Peter Cruddas, a businessman, philanthropist and Tory donor to the Lords. Other controversial nominations by Johnson have included the Evening Standard owner and son of a former KGB agent, Evegeny Lebedev.

However, while the commission must vet the nomination, the final decisions are taken by the prime minister of the day. It appears that Rishi Sunak may have decided that Johnson could not go ahead with several of his resignation honours, including Nadine Dorries, who was still sitting as an MP when Johnson is said to have proposed her peerage.

Although the commission does not publicly comment on individual cases, or the advice it gives, it has written to all party leaders to say that recent nominations have put its members in an “increasingly uncomfortable position”.

Change in the air

Given recent events, the time is right to ask whether the appointments process is fit for purpose. Currently, the commission is acting on an advisory, non-statutory basis. This means that its role can be altered without seeking permission from parliament. As recent events have shown, its advice can also be ignored, which has created a troublesome new precedent.

There are some potential solutions. Lord Norton, for example, has tabled a peerage nominations bill, which would establish a statutory commission. It is proposed this could have regard for the size of the chamber when making recommendations to the prime minister. The bill also establishes new criteria that someone should meet before receiving a nomination.

This would include “conspicuous merit” and a willingness and capacity to contribute to the chamber’s work. This could be one way of addressing the reputational damage caused by recent events, as well as achieve greater certainty surrounding appointment processes.

Stephen Clear does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.