Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

If dinosaurs died, how come there are birds? Caiden S., age 9, Wylie, Texas

Everyone knows what a bird is – and pretty much everyone knows what a dinosaur is. But not everyone is aware that birds evolved from dinosaurs approximately 160 million years ago.

In fact, birds and dinosaurs lived together for about 100 million years. Birds descended from a particular group of dinosaurs called the dromaeosaurs, or “running lizards,” which were a family of feathered theropod or “beast foot” dinosaurs that included velociraptor.

But when an asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago off the coast of what is now Mexico, dinosaurs went extinct – but some birds remained. You might wonder why.

By acting like detectives, scientists who specialize in bird evolution are trying to figure out why birds weren’t wiped out too. They piece together clues like fossils and other evidence about life on Earth long ago. For now, scientists have ideas about why birds survived, but no firm answers.

Perks of being toothless

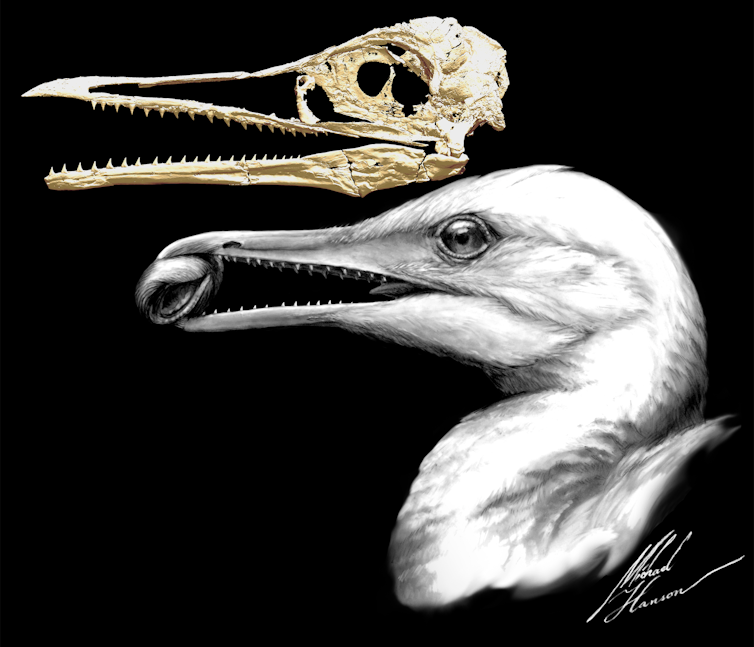

Today’s birds have no teeth. Instead they have beaks or bills, which come in many shapes and sizes for eating and drinking. But some of the birds that lived in dinosaur times actually had teeth. Others did not.

After the asteroid struck Earth long ago, all birds with teeth went extinct. But many of the toothless ones kept living. Some scientists think not having teeth is what allowed these birds to survive.

Fossils of early toothless birds show they were able to eat more plant-based food – specifically nuts, fruits and seeds. This meant they relied less on eating other animals than birds with teeth did. Some scientists think this difference in diet became a big advantage after the asteroid impact.

When the asteroid struck Earth, it immediately caused massive tsunamis and earthquakes. A giant pulse of heat from the impact caused enormous wildfires near where the asteroid hit. In the months that followed, huge amounts of dust filled the layer of air that surrounds Earth. It blocked the sun, making less light available for plants to grow.

For animals that ate plants, there was much less food. Many went extinct, which spelled trouble for the animals that ate them.

Since so many animal species died – and plants were struggling to get enough sunlight – food would have been hard to find if you were a bird. But if you could peck the ground and find buried seeds or nuts to eat, that might have made all the difference in your ability to survive as a species.

How science works

Of course, it’s possible other factors caused toothless birds to survive while their toothy cousins perished – including luck.

For now, it’s a mystery with no definite answer. This is how science works. Scientists formulate ideas or hypotheses using existing knowledge and information. Then they test their ideas – either by conducting experiments or by gathering more evidence. This information either supports or disproves their ideas.

So the scientists who study bird evolution are ready to revise the story of how birds made it and dinosaurs didn’t as they collect more information from rocks, fossils and ancient DNA.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

Chris Lituma does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.